Privacy is still a valued and valuable right. It should not be a mere benefit in a democratic society. But, in our current age privacy is becoming an increasingly threatened species. We are surrounded with social networks that share and mine our behaviors and we are assaulted by the snoopers and spooks from local and national governments.

From the Observer:

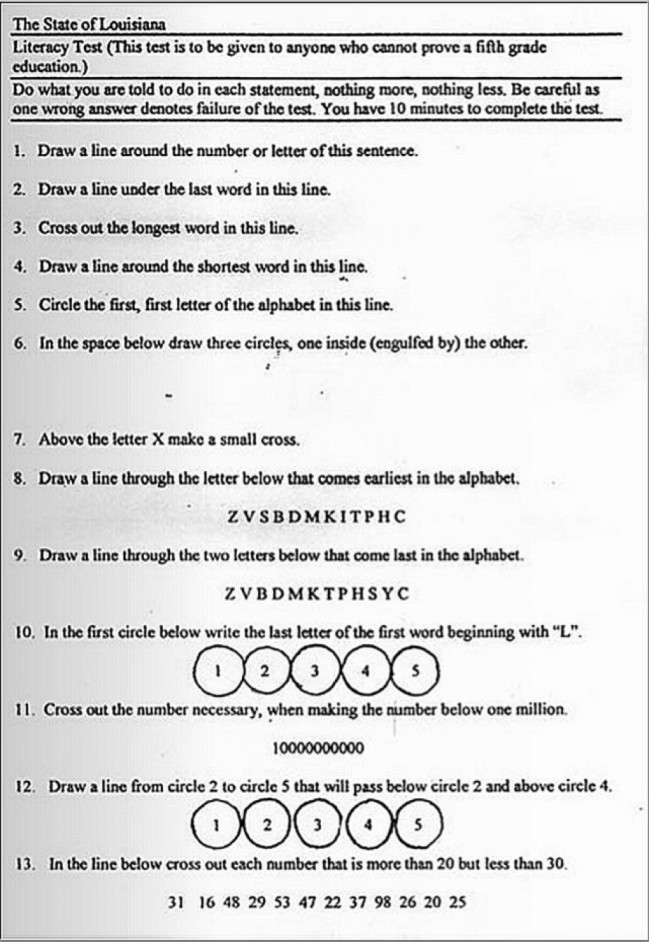

We have come to the end of privacy; our private lives, as our grandparents would have recognised them, have been winnowed away to the realm of the shameful and secret. To quote ex-tabloid hack Paul McMullan, “privacy is for paedos”. Insidiously, through small concessions that only mounted up over time, we have signed away rights and privileges that other generations fought for, undermining the very cornerstones of our personalities in the process. While outposts of civilisation fight pyrrhic battles, unplugging themselves from the web – “going dark” – the rest of us have come to accept that the majority of our social, financial and even sexual interactions take place over the internet and that someone, somewhere, whether state, press or corporation, is watching.

The past few years have brought an avalanche of news about the extent to which our communications are being monitored: WikiLeaks, the phone-hacking scandal, the Snowden files. Uproar greeted revelations about Facebook’s “emotional contagion” experiment (where it tweaked mathematical formulae driving the news feeds of 700,000 of its members in order to prompt different emotional responses). Cesar A Hidalgo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology described the Facebook news feed as “like a sausage… Everyone eats it, even though nobody knows how it is made”.

Sitting behind the outrage was a particularly modern form of disquiet – the knowledge that we are being manipulated, surveyed, rendered and that the intelligence behind this is artificial as well as human. Everything we do on the web, from our social media interactions to our shopping on Amazon, to our Netflix selections, is driven by complex mathematical formulae that are invisible and arcane.

Most recently, campaigners’ anger has turned upon the so-called Drip (Data Retention and Investigatory Powers) bill in the UK, which will see internet and telephone companies forced to retain and store their customers’ communications (and provide access to this data to police, government and up to 600 public bodies). Every week, it seems, brings a new furore over corporations – Apple, Google, Facebook – sidling into the private sphere. Often, it’s unclear whether the companies act brazenly because our governments play so fast and loose with their citizens’ privacy (“If you have nothing to hide, you’ve nothing to fear,” William Hague famously intoned); or if governments see corporations feasting upon the private lives of their users and have taken this as a licence to snoop, pry, survey.

We, the public, have looked on, at first horrified, then cynical, then bored by the revelations, by the well-meaning but seemingly useless protests. But what is the personal and psychological impact of this loss of privacy? What legal protection is afforded to those wishing to defend themselves against intrusion? Is it too late to stem the tide now that scenes from science fiction have become part of the fabric of our everyday world?

Novels have long been the province of the great What If?, allowing us to see the ramifications from present events extending into the murky future. As long ago as 1921, Yevgeny Zamyatin imagined One State, the transparent society of his dystopian novel, We. For Orwell, Huxley, Bradbury, Atwood and many others, the loss of privacy was one of the establishing nightmares of the totalitarian future. Dave Eggers’s 2013 novel The Circle paints a portrait of an America without privacy, where a vast, internet-based, multimedia empire surveys and controls the lives of its people, relying on strict adherence to its motto: “Secrets are lies, sharing is caring, and privacy is theft.” We watch as the heroine, Mae, disintegrates under the pressure of scrutiny, finally becoming one of the faceless, obedient hordes. A contemporary (and because of this, even more chilling) account of life lived in the glare of the privacy-free internet is Nikesh Shukla’s Meatspace, which charts the existence of a lonely writer whose only escape is into the shallows of the web. “The first and last thing I do every day,” the book begins, “is see what strangers are saying about me.”

Our age has seen an almost complete conflation of the previously separate spheres of the private and the secret. A taint of shame has crept over from the secret into the private so that anything that is kept from the public gaze is perceived as suspect. This, I think, is why defecation is so often used as an example of the private sphere. Sex and shitting were the only actions that the authorities in Zamyatin’s One State permitted to take place in private, and these remain the battlegrounds of the privacy debate almost a century later. A rather prim leaked memo from a GCHQ operative monitoring Yahoo webcams notes that “a surprising number of people use webcam conversations to show intimate parts of their body to the other person”.

It is to the bathroom that Max Mosley turns when we speak about his own campaign for privacy. “The need for a private life is something that is completely subjective,” he tells me. “You either would mind somebody publishing a film of you doing your ablutions in the morning or you wouldn’t. Personally I would and I think most people would.” In 2008, Mosley’s “sick Nazi orgy”, as the News of the World glossed it, featured in photographs published first in the pages of the tabloid and then across the internet. Mosley’s defence argued, successfully, that the romp involved nothing more than a “standard S&M prison scenario” and the former president of the FIA won £60,000 damages under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Now he has rounded on Google and the continued presence of both photographs and allegations on websites accessed via the company’s search engine. If you type “Max Mosley” into Google, the eager autocomplete presents you with “video,” “case”, “scandal” and “with prostitutes”. Half-way down the first page of the search we find a link to a professional-looking YouTube video montage of the NotW story, with no acknowledgment that the claims were later disproved. I watch it several times. I feel a bit grubby.

“The moment the Nazi element of the case fell apart,” Mosley tells me, “which it did immediately, because it was a lie, any claim for public interest also fell apart.”

Here we have a clear example of the blurred lines between secrecy and privacy. Mosley believed that what he chose to do in his private life, even if it included whips and nipple-clamps, should remain just that – private. The News of the World, on the other hand, thought it had uncovered a shameful secret that, given Mosley’s professional position, justified publication. There is a momentary tremor in Mosley’s otherwise fluid delivery as he speaks about the sense of invasion. “Your privacy or your private life belongs to you. Some of it you may choose to make available, some of it should be made available, because it’s in the public interest to make it known. The rest should be yours alone. And if anyone takes it from you, that’s theft and it’s the same as the theft of property.”

Mosley has scored some recent successes, notably in continental Europe, where he has found a culture more suspicious of Google’s sweeping powers than in Britain or, particularly, the US. Courts in France and then, interestingly, Germany, ordered Google to remove pictures of the orgy permanently, with far-reaching consequences for the company. Google is appealing against the rulings, seeing it as absurd that “providers are required to monitor even the smallest components of content they transmit or store for their users”. But Mosley last week extended his action to the UK, filing a claim in the high court in London.

Mosley’s willingness to continue fighting, even when he knows that it means keeping alive the image of his white, septuagenarian buttocks in the minds (if not on the computers) of the public, seems impressively principled. He has fallen victim to what is known as the Streisand Effect, where his very attempt to hide information about himself has led to its proliferation (in 2003 Barbra Streisand tried to stop people taking pictures of her Malibu home, ensuring photos were posted far and wide). Despite this, he continues to battle – both in court, in the media and by directly confronting the websites that continue to display the pictures. It is as if he is using that initial stab of shame, turning it against those who sought to humiliate him. It is noticeable that, having been accused of fetishising one dark period of German history, he uses another to attack Google. “I think, because of the Stasi,” he says, “the Germans can understand that there isn’t a huge difference between the state watching everything you do and Google watching everything you do. Except that, in most European countries, the state tends to be an elected body, whereas Google isn’t. There’s not a lot of difference between the actions of the government of East Germany and the actions of Google.”

All this brings us to some fundamental questions about the role of search engines. Is Google the de facto librarian of the internet, given that it is estimated to handle 40% of all traffic? Is it something more than a librarian, since its algorithms carefully (and with increasing use of your personal data) select the sites it wants you to view? To what extent can Google be held responsible for the content it puts before us?

Read the entire article here.

Those of us who live relatively comfortable lives in the West are confronted with numerous and not insignificant stresses on a daily basis. There are the stresses of politics, parenting, work life balance, intolerance and financial, to name but a few.

Those of us who live relatively comfortable lives in the West are confronted with numerous and not insignificant stresses on a daily basis. There are the stresses of politics, parenting, work life balance, intolerance and financial, to name but a few.