Pathological criminals and the non-criminals who seek to understand them have no doubt co-existed since humans first learned to steal from and murder one another.

Pathological criminals and the non-criminals who seek to understand them have no doubt co-existed since humans first learned to steal from and murder one another.

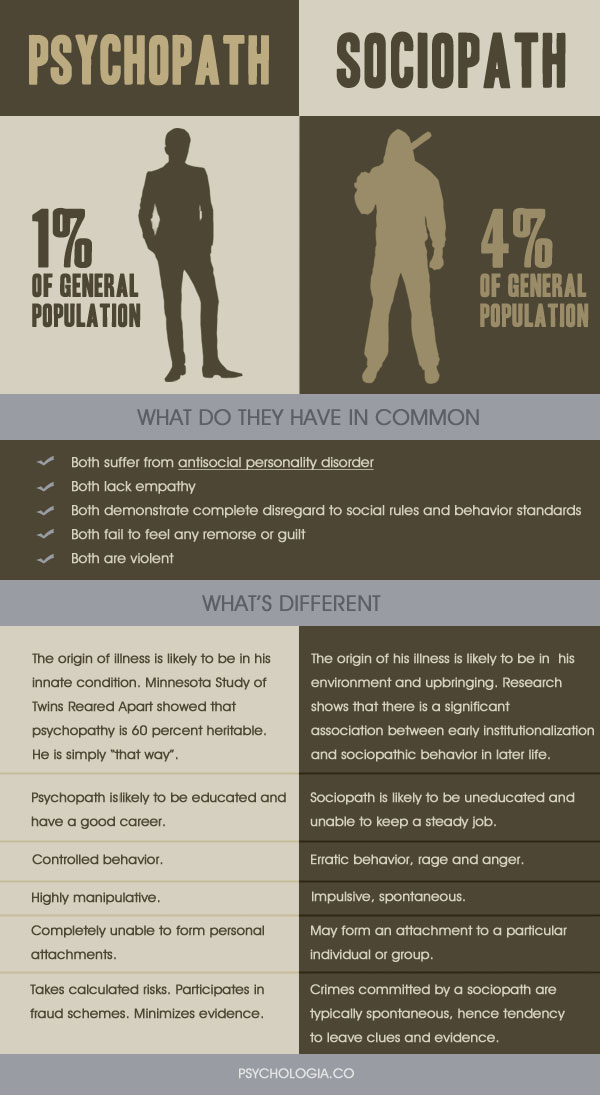

So while we may be no clearer in fully understanding the underlying causes of anti-social, destructive and violent behavior many researchers continue their quests. In one camp are those who maintain that such behavior is learned or comes as a consequence of poor choices or life-events, usually traumatic, or through exposure to an acute psychological or physiological stressor. In the other camp, are those who argue that genes and their subsequent expression, especially those controlling brain function, are a principal cause.

Some recent neurological studies of criminals and psychopaths shows fascinating, though not unequivocal, results.

From the Wall Street Journal:

The scientific study of crime got its start on a cold, gray November morning in 1871, on the east coast of Italy. Cesare Lombroso, a psychiatrist and prison doctor at an asylum for the criminally insane, was performing a routine autopsy on an infamous Calabrian brigand named Giuseppe Villella. Lombroso found an unusual indentation at the base of Villella’s skull. From this singular observation, he would go on to become the founding father of modern criminology.

Lombroso’s controversial theory had two key points: that crime originated in large measure from deformities of the brain and that criminals were an evolutionary throwback to more primitive species. Criminals, he believed, could be identified on the basis of physical characteristics, such as a large jaw and a sloping forehead. Based on his measurements of such traits, Lombroso created an evolutionary hierarchy, with Northern Italians and Jews at the top and Southern Italians (like Villella), along with Bolivians and Peruvians, at the bottom.

These beliefs, based partly on pseudoscientific phrenological theories about the shape and size of the human head, flourished throughout Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Lombroso was Jewish and a celebrated intellectual in his day, but the theory he spawned turned out to be socially and scientifically disastrous, not least by encouraging early-20th-century ideas about which human beings were and were not fit to reproduce—or to live at all.

The racial side of Lombroso’s theory fell into justifiable disrepute after the horrors of World War II, but his emphasis on physiology and brain traits has proved to be prescient. Modern-day scientists have now developed a far more compelling argument for the genetic and neurological components of criminal behavior. They have uncovered, quite literally, the anatomy of violence, at a time when many of us are preoccupied by the persistence of violent outrages in our midst.

The field of neurocriminology—using neuroscience to understand and prevent crime—is revolutionizing our understanding of what drives “bad” behavior. More than 100 studies of twins and adopted children have confirmed that about half of the variance in aggressive and antisocial behavior can be attributed to genetics. Other research has begun to pinpoint which specific genes promote such behavior.

Brain-imaging techniques are identifying physical deformations and functional abnormalities that predispose some individuals to violence. In one recent study, brain scans correctly predicted which inmates in a New Mexico prison were most likely to commit another crime after release. Nor is the story exclusively genetic: A poor environment can change the early brain and make for antisocial behavior later in life.

Most people are still deeply uncomfortable with the implications of neurocriminology. Conservatives worry that acknowledging biological risk factors for violence will result in a society that takes a soft approach to crime, holding no one accountable for his or her actions. Liberals abhor the potential use of biology to stigmatize ostensibly innocent individuals. Both sides fear any seeming effort to erode the idea of human agency and free will.

It is growing harder and harder, however, to avoid the mounting evidence. With each passing year, neurocriminology is winning new adherents, researchers and practitioners who understand its potential to transform our approach to both crime prevention and criminal justice.

The genetic basis of criminal behavior is now well established. Numerous studies have found that identical twins, who have all of their genes in common, are much more similar to each other in terms of crime and aggression than are fraternal twins, who share only 50% of their genes.

In a landmark 1984 study, my colleague Sarnoff Mednick found that children in Denmark who had been adopted from parents with a criminal record were more likely to become criminals in adulthood than were other adopted kids. The more offenses the biological parents had, the more likely it was that their offspring would be convicted of a crime. For biological parents who had no offenses, 13% of their sons had been convicted; for biological parents with three or more offenses, 25% of their sons had been convicted.

As for environmental factors that affect the young brain, lead is neurotoxic and particularly damages the prefrontal region, which regulates behavior. Measured lead levels in our bodies tend to peak at 21 months—an age when toddlers are apt to put their fingers into their mouths. Children generally pick up lead in soil that has been contaminated by air pollution and dumping.

Rising lead levels in the U.S. from 1950 through the 1970s neatly track increases in violence 20 years later, from the ’70s through the ’90s. (Violence peaks when individuals are in their late teens and early 20s.) As lead in the environment fell in the ’70s and ’80s—thanks in large part to the regulation of gasoline—violence fell correspondingly. No other single factor can account for both the inexplicable rise in violence in the U.S. until 1993 and the precipitous drop since then.

Lead isn’t the only culprit. Other factors linked to higher aggression and violence in adulthood include smoking and drinking by the mother before birth, complications during birth and poor nutrition early in life.

Genetics and environment may work together to encourage violent behavior. One pioneering study in 2002 by Avshalom Caspi and Terrie Moffitt of Duke University genotyped over 1,000 individuals in a community in New Zealand and assessed their levels of antisocial behavior in adulthood. They found that a genotype conferring low levels of the enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), when combined with early child abuse, predisposed the individual to later antisocial behavior. Low MAOA has been linked to reduced volume in the amygdala—the emotional center of the brain—while physical child abuse can damage the frontal part of the brain, resulting in a double hit.

Brain-imaging studies have also documented impairments in offenders. Murderers, for instance, tend to have poorer functioning in the prefrontal cortex—the “guardian angel” that keeps the brakes on impulsive, disinhibited behavior and volatile emotions.

Read the entire article following the jump.

Image: The Psychopath Test by Jon Ronson, book cover. Courtesy of Goodreads.

New research — probably conducted by a group of early-risers — shows that people who prefer to stay up late, and rise late, are more likely to be narcissistic, insensitive, manipulative and psychopathic.

New research — probably conducted by a group of early-risers — shows that people who prefer to stay up late, and rise late, are more likely to be narcissistic, insensitive, manipulative and psychopathic. Pathological criminals and the non-criminals who seek to understand them have no doubt co-existed since humans first learned to steal from and murder one another.

Pathological criminals and the non-criminals who seek to understand them have no doubt co-existed since humans first learned to steal from and murder one another. Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath?

Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath?