Two million people annually take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator assessment. Over 10,000 businesses and 2,500 colleges in the United States use the test.

Two million people annually take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator assessment. Over 10,000 businesses and 2,500 colleges in the United States use the test.

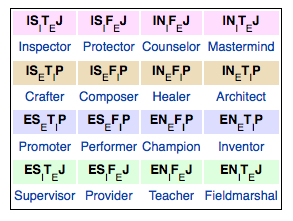

It’s very likely that you have taken the test at some point in your life: during high school, or to get into university or to secure your first job. The test categorizes humans along 4 discrete axes (or dichotomies) of personality types: Extraversion (E) and Introversion (I); Sensing (S) and Intuition (N); Thinking (T) and Feeling (F); Judging (J) and Perceiving (P). If your have a partner it’s likely that he or she has, at sometime or another, (mis-)labeled you as an E or an I, and as a “feeler” rather than a “thinker”, and so on. Countless arguments will have ensued.

[div class=attrib]From the Washington Post:[end-div]

Some grandmothers pass down cameo necklaces. Katharine Cook Briggs passed down the world’s most widely used personality test.

Chances are you’ve taken the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or will. Roughly 2 million people a year do. It has become the gold standard of psychological assessments, used in businesses, government agencies and educational institutions. Along the way, it has spawned a multimillion-dollar business around its simple concept that everyone fits one of 16 personality types.

Now, 50 years after the first time anyone paid money for the test, the Myers-Briggs legacy is reaching the end of the family line. The youngest heirs don’t want it. And it’s not clear whether organizations should, either.

That’s not to say it hasn’t had a major influence.

More than 10,000 companies, 2,500 colleges and universities and 200 government agencies in the United States use the test. From the State Department to McKinsey & Co., it’s a rite of passage. It’s estimated that 50 million people have taken the Myers-Briggs personality test since the Educational Testing Service first added the research to its portfolio in 1962.

The test, whose first research guinea pigs were George Washington University students, has seen financial success commensurate to this cultlike devotion among its practitioners. CPP, the private company that publishes Myers-Briggs, brings in roughly $20 million a year from it and the 800 other products, such as coaching guides, that it has spawned.

Yet despite its widespread use and vast financial success, and although it was derived from the work of Carl Jung, one of the most famous psychologists of the 20th century, the test is highly questioned by the scientific community.

To begin even before its arrival in Washington: Myers-Briggs traces its history to 1921, when Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, published his theory of personality types in the book “Psychologische Typen.” Jung had become well known for his pioneering work in psychoanalysis and close collaboration with Sigmund Freud, though by the 1920s the two had severed ties.

Psychoanalysis was a young field and one many regarded skeptically. Still, it had made its way across the Atlantic not only to the university offices of scientists but also to the home of a mother in Washington.

Katharine Cook Briggs was a voracious reader of the new psychology books coming out in Europe, and she shared her fascination with Jung’s latest work — in which he developed the concepts of introversion and extroversion — with her daughter, Isabel Myers. They would later use Jung’s work as a basis for their own theory, which would become the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. MBTI is their framework for classifying personality types along four distinct axes: introversion vs. extroversion, sensing vs. intuition, thinking vs. feeling and judging vs. perceiving. A person, according to their hypothesis, has one dominant preference in each of the four pairs. For example, he might be introverted, a sensor, a thinker and a perceiver. Or, in Myers-Briggs shorthand, an “ISTP.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article following the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Keirsey Temperament Sorter, which utilizes Myers-Briggs dichotomies to group personalities into 16 types. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]