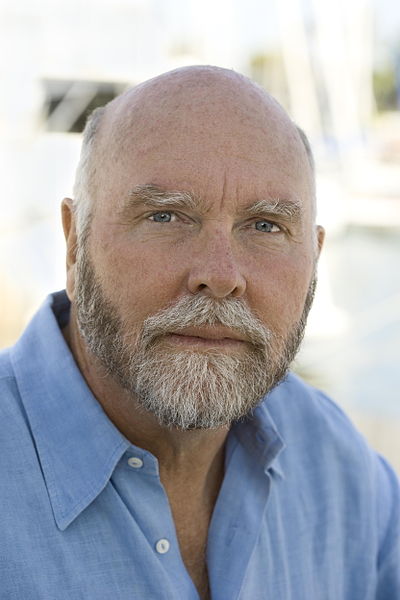

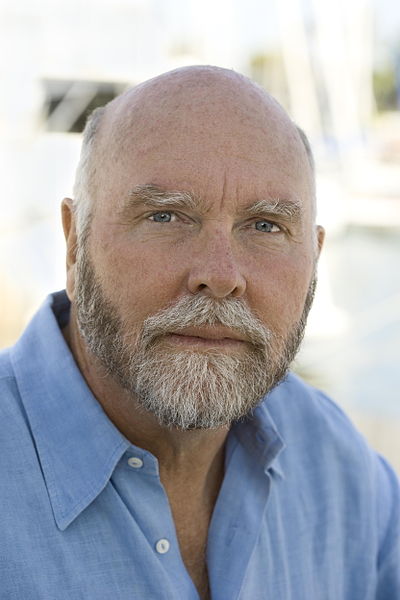

Molecular-biology entrepreneur and genomics engineering pioneer, Craig Venter, is at it again. In his new book, Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life, Venter explains his grand ideas and the coming era of discovery.

Molecular-biology entrepreneur and genomics engineering pioneer, Craig Venter, is at it again. In his new book, Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life, Venter explains his grand ideas and the coming era of discovery.

From ars technica:

J Craig Venter has been a molecular-biology pioneer for two decades. After developing expressed sequence tags in the 90s, he led the private effort to map the human genome, publishing the results in 2001. In 2010, the J Craig Venter Institute manufactured the entire genome of a bacterium, creating the first synthetic organism.

Now Venter, author of Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life, explains the coming era of discovery.

Wired: In Life at the Speed of Light, you argue that humankind is entering a new phase of evolution. How so?

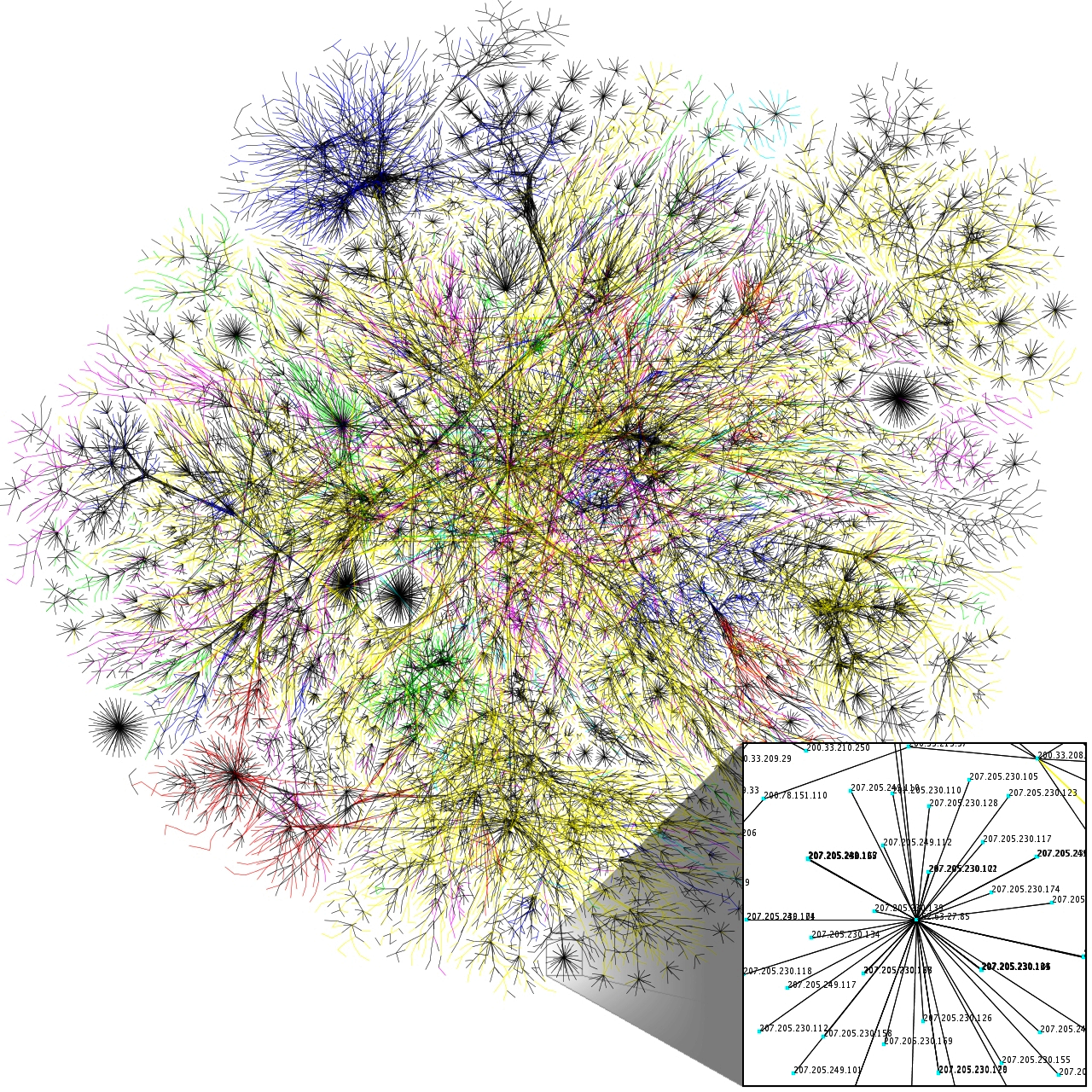

J Craig Venter: As the industrial age is drawing to a close, I think that we’re witnessing the dawn of the era of biological design. DNA, as digitized information, is accumulating in computer databases. Thanks to genetic engineering, and now the field of synthetic biology, we can manipulate DNA to an unprecedented extent, just as we can edit software in a computer. We can also transmit it as an electromagnetic wave at or near the speed of light and, via a “biological teleporter,” use it to recreate proteins, viruses, and living cells at another location, changing forever how we view life.

So you view DNA as the software of life?

All the information needed to make a living, self-replicating cell is locked up within the spirals of DNA’s double helix. As we read and interpret that software of life, we should be able to completely understand how cells work, then change and improve them by writing new cellular software.

The software defines the manufacture of proteins that can be viewed as its hardware, the robots and chemical machines that run a cell. The software is vital because the cell’s hardware wears out. Cells will die in minutes to days if they lack their genetic-information system. They will not evolve, they will not replicate, and they will not live.

Of all the experiments you have done over the past two decades involving the reading and manipulation of the software of life, which are the most important?

I do think the synthetic cell is my most important contribution. But if I were to select a single study, paper, or experimental result that has really influenced my understanding of life more than any other, I would choose one that my team published in 2007, in a paper with the title Genome Transplantation in Bacteria: Changing One Species to Another. The research that led to this paper in the journal Science not only shaped my view of the fundamentals of life but also laid the groundwork to create the first synthetic cell. Genome transplantation not only provided a way to carry out a striking transformation, converting one species into another, but would also help prove that DNA is the software of life.

What has happened since your announcement in 2010 that you created a synthetic cell, JCVI-syn1.0?

At the time, I said that the synthetic cell would give us a better understanding of the fundamentals of biology and how life works, help develop techniques and tools for vaccine and pharmaceutical development, enable development of biofuels and biochemicals, and help to create clean water, sources of food, textiles, bioremediation. Three years on that vision is being borne out.

Your book contains a dramatic account of the slog and setbacks that led to the creation of this first synthetic organism. What was your lowest point?

When we started out creating JCVI-syn1.0 in the lab, we had selected M. genitalium because of its extremely small genome. That decision we would come to really regret: in the laboratory, M. genitalium grows slowly. So whereas E. coli divides into daughter cells every 20 minutes, M. genitalium requires 12 hours to make a copy of itself. With logarithmic growth, it’s the difference between having an experimental result in 24 hours versus several weeks. It felt like we were working really hard to get nowhere at all. I changed the target to the M. mycoides genome. It’s twice as large as that of genitalium, but it grows much faster. In the end, that move made all the difference.

Some of your peers were blown away by the synthetic cell; others called it a technical tour de force. But there were also those who were underwhelmed because it was not “life from scratch.”

They haven’t thought much about what they are actually trying to say when they talk about “life from scratch.” How about baking a cake “from scratch”? You could buy one and then ice it at home. Or buy a cake mix, to which you add only eggs, water and oil. Or combining the individual ingredients, such as baking powder, sugar, salt, eggs, milk, shortening and so on. But I doubt that anyone would mean formulating his own baking powder by combining sodium, hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen to produce sodium bicarbonate, or producing homemade corn starch. If we apply the same strictures to creating life “from scratch,” it could mean producing all the necessary molecules, proteins, lipids, organelles, DNA, and so forth from basic chemicals or perhaps even from the fundamental elements carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphate, iron, and so on.

There’s a parallel effort to create virtual life, which you go into in the book. How sophisticated are these models of cells in silico?

In the past year we have really seen how virtual cells can help us understand the real things. This work dates back to 1996 when Masaru Tomita and his students at the Laboratory for Bioinformatics at Keio started investigating the molecular biology of Mycoplasma genitalium—which we had sequenced in 1995—and by the end of that year had established the E-Cell Project. The most recent work on Mycoplasma genitalium has been done in America, by the systems biologist Markus W Covert, at Stanford University. His team used our genome data to create a virtual version of the bacterium that came remarkably close to its real-life counterpart.

You’ve discussed the ethics of synthetic organisms for a long time—where is the ethical argument today?

The Janus-like nature of innovation—its responsible use and so on—was evident at the very birth of human ingenuity, when humankind first discovered how to make fire on demand. (Do I use it burn down a rival’s settlement, or to keep warm?) Every few months, another meeting is held to discuss how powerful technology cuts both ways. It is crucial that we invest in underpinning technologies, science, education, and policy in order to ensure the safe and efficient development of synthetic biology. Opportunities for public debate and discussion on this topic must be sponsored, and the lay public must engage. But it is important not to lose sight of the amazing opportunities that this research presents. Synthetic biology can help address key challenges facing the planet and its population. Research in synthetic biology may lead to new things such as programmed cells that self-assemble at the sites of disease to repair damage.

What worries you more: bioterror or bioerror?

I am probably more concerned about an accidental slip. Synthetic biology increasingly relies on the skills of scientists who have little experience in biology, such as mathematicians and electrical engineers. The democratization of knowledge and the rise of “open-source biology;” the availability of kitchen-sink versions of key laboratory tools, such as the DNA-copying method PCR, make it easier for anyone—including those outside the usual networks of government, commercial, and university laboratories and the culture of responsible training and biosecurity—to play with the software of life.

Following the precautionary principle, should we abandon synthetic biology?

My greatest fear is not the abuse of technology, but that we will not use it at all, and turn our backs to an amazing opportunity at a time when we are over-populating our planet and changing environments forever.

You’re bullish about where this is headed.

I am—and a lot of that comes from seeing the next generation of synthetic biologists. We can get a view of what the future holds from a series of contests that culminate in a yearly event in Cambridge, Massachusetts—the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition. High-school and college students shuffle a standard set of DNA subroutines into something new. It gives me hope for the future.

You’ve been working to convert DNA into a digital signal that can be transmitted to a unit which then rebuilds an organism.

At Synthetic Genomics, Inc [which Venter founded with his long-term collaborator, the Nobel laureate Ham Smith], we can feed digital DNA code into a program that works out how to re-synthesize the sequence in the lab. This automates the process of designing overlapping pieces of DNA base-pairs, called oligonucleotides, adding watermarks, and then feeding them into the synthesizer. The synthesizer makes the oligonucleotides, which are pooled and assembled using what we call our Gibson-assembly robot (named after my talented colleague Dan Gibson). NASA has funded us to carry out experiments at its test site in the Mojave Desert. We will be using the JCVI mobile lab, which is equipped with soil-sampling, DNA-isolation and DNA sequencing equipment, to test the steps for autonomously isolating microbes from soil, sequencing their DNA and then transmitting the information to the cloud with what we call a “digitized-life-sending unit”. The receiving unit, where the transmitted DNA information can be downloaded and reproduced anew, has a number of names at present, including “digital biological converter,” “biological teleporter,” and—the preference of former US Wired editor-in-chief and CEO of 3D Robotics, Chris Anderson—”life replicator”.

Read the entire article here.

Image: J Craig Venter. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

We all need heroes. So, if you wish to become one, you would stand a better chance if you took your dying breaths atop a hill. Also, it would really help your cause if you arrived via virgin birth.

We all need heroes. So, if you wish to become one, you would stand a better chance if you took your dying breaths atop a hill. Also, it would really help your cause if you arrived via virgin birth.

Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world.

Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world.

Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers.

Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers. Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource.

Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource. “You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate:

“You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate: Skeptic

Skeptic Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable.

Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable. Classic dystopian novels from the likes of

Classic dystopian novels from the likes of

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq.

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq. [div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div] Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath?

Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath? Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process.

Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process. David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies.

David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies.