Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney.

Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney.

So, we mourn and celebrate with an excerpt from his 1995 Nobel acceptance speech. You can find more on Heaney’s remarkable life in words, here, at Poetry Foundation.

From the Independent:

When I first encountered the name of the city of Stockholm, I little thought that I would ever visit it, never mind end up being welcomed to it as a guest of the Swedish Academy and the Nobel Foundation.

At the time I am thinking of, such an outcome was not just beyond expectation: it was simply beyond conception. In the nineteen forties, when I was the eldest child of an ever-growing family in rural Co. Derry, we crowded together in the three rooms of a traditional thatched farmstead and lived a kind of den-life which was more or less emotionally and intellectually proofed against the outside world. It was an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the night sounds of the horse in the stable beyond one bedroom wall mingled with the sounds of adult conversation from the kitchen beyond the other. We took in everything that was going on, of course – rain in the trees, mice on the ceiling, a steam train rumbling along the railway line one field back from the house – but we took it in as if we were in the doze of hibernation. Ahistorical, pre-sexual, in suspension between the archaic and the modern, we were as susceptible and impressionable as the drinking water that stood in a bucket in our scullery: every time a passing train made the earth shake, the surface of that water used to ripple delicately, concentrically, and in utter silence.

But it was not only the earth that shook for us: the air around and above us was alive and signalling too. When a wind stirred in the beeches, it also stirred an aerial wire attached to the topmost branch of the chestnut tree. Down it swept, in through a hole bored in the corner of the kitchen window, right on into the innards of our wireless set where a little pandemonium of burbles and squeaks would suddenly give way to the voice of a BBC newsreader speaking out of the unexpected like a deus ex machina. And that voice too we could hear in our bedroom, transmitting from beyond and behind the voices of the adults in the kitchen; just as we could often hear, behind and beyond every voice, the frantic, piercing signalling of morse code.

We could pick up the names of neighbours being spoken in the local accents of our parents, and in the resonant English tones of the newsreader the names of bombers and of cities bombed, of war fronts and army divisions, the numbers of planes lost and of prisoners taken, of casualties suffered and advances made; and always, of course, we would pick up too those other, solemn and oddly bracing words, “the enemy” and “the allies”. But even so, none of the news of these world-spasms entered me as terror. If there was something ominous in the newscaster’s tones, there was something torpid about our understanding of what was at stake; and if there was something culpable about such political ignorance in that time and place, there was something positive about the security I inhabited as a result of it.

The wartime, in other words, was pre-reflective time for me. Pre-literate too. Pre-historical in its way. Then as the years went on and my listening became more deliberate, I would climb up on an arm of our big sofa to get my ear closer to the wireless speaker. But it was still not the news that interested me; what I was after was the thrill of story, such as a detective serial about a British special agent called Dick Barton or perhaps a radio adaptation of one of Capt. W.E. Johns’s adventure tales about an RAF flying ace called Biggles. Now that the other children were older and there was so much going on in the kitchen, I had to get close to the actual radio set in order to concentrate my hearing, and in that intent proximity to the dial I grew familiar with the names of foreign stations, with Leipzig and Oslo and Stuttgart and Warsaw and, of course, with Stockholm.

I also got used to hearing short bursts of foreign languages as the dial hand swept round from BBC to Radio Eireann, from the intonations of London to those of Dublin, and even though I did not understand what was being said in those first encounters with the gutturals and sibilants of European speech, I had already begun a journey into the wideness of the world beyond. This in turn became a journey into the wideness of language, a journey where each point of arrival – whether in one’s poetry or one’s life turned out to be a stepping stone rather than a destination, and it is that journey which has brought me now to this honoured spot. And yet the platform here feels more like a space station than a stepping stone, so that is why, for once in my life, I am permitting myself the luxury of walking on air.

*

I credit poetry for making this space-walk possible. I credit it immediately because of a line I wrote fairly recently instructing myself (and whoever else might be listening) to “walk on air against your better judgement”. But I credit it ultimately because poetry can make an order as true to the impact of external reality and as sensitive to the inner laws of the poet’s being as the ripples that rippled in and rippled out across the water in that scullery bucket fifty years ago. An order where we can at last grow up to that which we stored up as we grew. An order which satisfies all that is appetitive in the intelligence and prehensile in the affections. I credit poetry, in other words, both for being itself and for being a help, for making possible a fluid and restorative relationship between the mind’s centre and its circumference, between the child gazing at the word “Stockholm” on the face of the radio dial and the man facing the faces that he meets in Stockholm at this most privileged moment. I credit it because credit is due to it, in our time and in all time, for its truth to life, in every sense of that phrase.

*

To begin with, I wanted that truth to life to possess a concrete reliability, and rejoiced most when the poem seemed most direct, an upfront representation of the world it stood in for or stood up for or stood its ground against. Even as a schoolboy, I loved John Keats’s ode “To Autumn” for being an ark of the covenant between language and sensation; as an adolescent, I loved Gerard Manley Hopkins for the intensity of his exclamations which were also equations for a rapture and an ache I didn’t fully know I knew until I read him; I loved Robert Frost for his farmer’s accuracy and his wily down-to-earthness; and Chaucer too for much the same reasons. Later on I would find a different kind of accuracy, a moral down-to-earthness to which I responded deeply and always will, in the war poetry of Wilfred Owen, a poetry where a New Testament sensibility suffers and absorbs the shock of the new century’s barbarism. Then later again, in the pure consequence of Elizabeth Bishop’s style, in the sheer obduracy of Robert Lowell’s and in the barefaced confrontation of Patrick Kavanagh’s, I encountered further reasons for believing in poetry’s ability – and responsibility – to say what happens, to “pity the planet,” to be “not concerned with Poetry.”

This temperamental disposition towards an art that was earnest and devoted to things as they are was corroborated by the experience of having been born and brought up in Northern Ireland and of having lived with that place even though I have lived out of it for the past quarter of a century. No place in the world prides itself more on its vigilance and realism, no place considers itself more qualified to censure any flourish of rhetoric or extravagance of aspiration. So, partly as a result of having internalized these attitudes through growing up with them, and partly as a result of growing a skin to protect myself against them, I went for years half-avoiding and half- resisting the opulence and extensiveness of poets as different as Wallace Stevens and Rainer Maria Rilke; crediting insufficiently the crystalline inwardness of Emily Dickinson, all those forked lightnings and fissures of association; and missing the visionary strangeness of Eliot. And these more or less costive attitudes were fortified by a refusal to grant the poet any more license than any other citizen; and they were further induced by having to conduct oneself as a poet in a situation of ongoing political violence and public expectation. A public expectation, it has to be said, not of poetry as such but of political positions variously approvable by mutually disapproving groups.

In such circumstances, the mind still longs to repose in what Samuel Johnson once called with superb confidence “the stability of truth”, even as it recognizes the destabilizing nature of its own operations and enquiries. Without needing to be theoretically instructed, consciousness quickly realizes that it is the site of variously contending discourses. The child in the bedroom, listening simultaneously to the domestic idiom of his Irish home and the official idioms of the British broadcaster while picking up from behind both the signals of some other distress, that child was already being schooled for the complexities of his adult predicament, a future where he would have to adjudicate among promptings variously ethical, aesthetical, moral, political, metrical, sceptical, cultural, topical, typical, post-colonial and, taken all together, simply impossible. So it was that I found myself in the mid-nineteen seventies in another small house, this time in Co. Wicklow south of Dublin, with a young family of my own and a slightly less imposing radio set, listening to the rain in the trees and to the news of bombings closer to home-not only those by the Provisional IRA in Belfast but equally atrocious assaults in Dublin by loyalist paramilitaries from the north. Feeling puny in my predicaments as I read about the tragic logic of Osip Mandelstam’s fate in the 1930s, feeling challenged yet steadfast in my noncombatant status when I heard, for example, that one particularly sweetnatured school friend had been interned without trial because he was suspected of having been involved in a political killing. What I was longing for was not quite stability but an active escape from the quicksand of relativism, a way of crediting poetry without anxiety or apology. In a poem called “Exposure” I wrote then:

If I could come on meteorite!

Instead, I walk through damp leaves,

Husks, the spent flukes of autumn,

Imagining a hero

On some muddy compound,

His gift like a slingstone

Whirled for the desperate.

How did I end up like this?

I often think of my friends’

Beautiful prismatic counselling

And the anvil brains of some who hate me

As I sit weighing and weighing

My responsible tristia.

For what? For the ear? For the people?

For what is said behind-backs?

Rain comes down through the alders,

Its low conducive voices

Mutter about let-downs and erosions

And yet each drop recalls

The diamond absolutes.

I am neither internee nor informer;

An inner émigré, a grown long-haired

And thoughtful; a wood-kerne

Escaped from the massacre,

Taking protective colouring

From bole and bark, feeling

Every wind that blows;

Who, blowing up these sparks

For their meagre heat, have missed

The once in a lifetime portent,

The comet’s pulsing rose.

(from North)

Read the entire article here.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

The French have a formal language police.

The French have a formal language police. Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?

Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?

Seamus Heaney, poet, Nobel Laureate and above all observer of the Irish condition passed away last week.

Seamus Heaney, poet, Nobel Laureate and above all observer of the Irish condition passed away last week. Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney.

Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney. Do you prefer the Beatles to Beethoven? Do you prefer Rembrandt over the Sunday comics or the latest Marvel? Do you read Patterson or Proust? Gary Gutting professor of philosophy argues that the distinguishing value of aesthetics must drive us to appreciate fine art over popular work. So, you had better dust off those volumes of Shakespeare.

Do you prefer the Beatles to Beethoven? Do you prefer Rembrandt over the Sunday comics or the latest Marvel? Do you read Patterson or Proust? Gary Gutting professor of philosophy argues that the distinguishing value of aesthetics must drive us to appreciate fine art over popular work. So, you had better dust off those volumes of Shakespeare. Iain (M.) Banks is now where he rightfully belongs — hurtling through space. Though, we fear that he may well not be traveling as fast as he would have wished.

Iain (M.) Banks is now where he rightfully belongs — hurtling through space. Though, we fear that he may well not be traveling as fast as he would have wished. Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence?

Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence? On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great.

On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great. If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time.

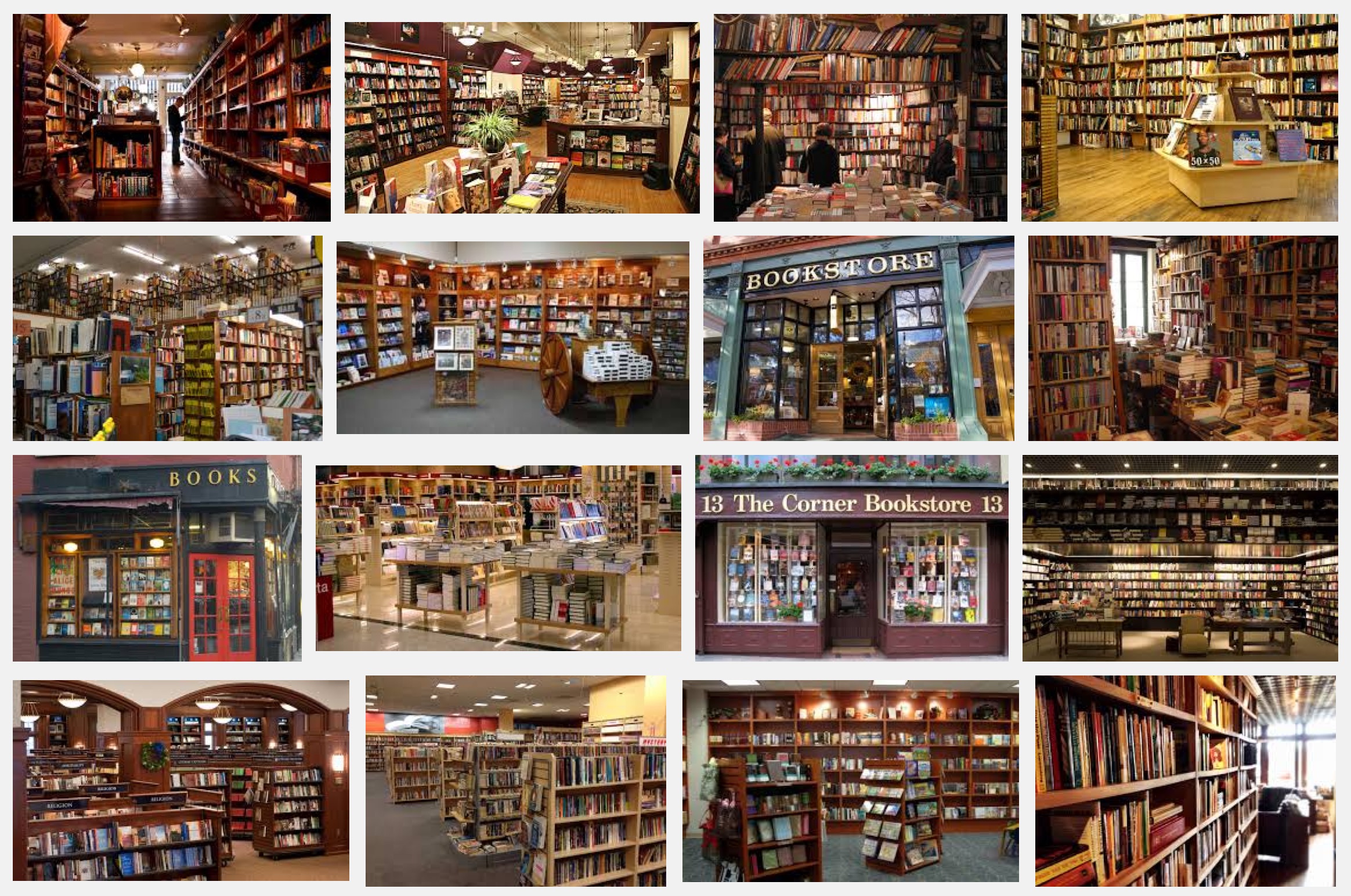

If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time. Last week Amazon purchased Goodreads the online book review site. Since 2007 Goodreads has grown to become home to over 16 million members who share a passion for discovering and sharing great literature. Now, with Amazon’s acquisition many are concerned that this represents another step towards a monolithic and monopolistic enterprise that controls vast swathes of the market. While Amazon’s innovation has upended the bricks-and-mortar worlds of publishing and retailing, its increasingly dominant market power raises serious concerns over access, distribution and choice. This is another worrying example of the so-called filter bubble — where increasingly edited selections and personalized recommendations act to limit and dumb-down content.

Last week Amazon purchased Goodreads the online book review site. Since 2007 Goodreads has grown to become home to over 16 million members who share a passion for discovering and sharing great literature. Now, with Amazon’s acquisition many are concerned that this represents another step towards a monolithic and monopolistic enterprise that controls vast swathes of the market. While Amazon’s innovation has upended the bricks-and-mortar worlds of publishing and retailing, its increasingly dominant market power raises serious concerns over access, distribution and choice. This is another worrying example of the so-called filter bubble — where increasingly edited selections and personalized recommendations act to limit and dumb-down content. Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

Emily Dickinson has been much written about, but still remains enigmatic. Many of her peers thought her to be eccentric and withdrawn. Only after her death did the full extent of her prolific writing become apparent. To this day, her unique poetry is regarded as having ushered in a new era of personal observation and expression.

Emily Dickinson has been much written about, but still remains enigmatic. Many of her peers thought her to be eccentric and withdrawn. Only after her death did the full extent of her prolific writing become apparent. To this day, her unique poetry is regarded as having ushered in a new era of personal observation and expression.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another. The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names. A month in to fall and it really does now seem like Autumn — leaves are turning and falling, jackets have reappeared, brisk morning walks are now shrouded in darkness.

A month in to fall and it really does now seem like Autumn — leaves are turning and falling, jackets have reappeared, brisk morning walks are now shrouded in darkness. Author Joe Queenan explains why reading over 6,000 books may be because, as he puts it, he “find[s] ‘reality’ a bit of a disappointment”.

Author Joe Queenan explains why reading over 6,000 books may be because, as he puts it, he “find[s] ‘reality’ a bit of a disappointment”.