Fascinating insight into the Burning Man festival courtesy of co-founder, Larry Harvey. It may be more like Wall Street than Haight-Ashbury.

[div class=attrib]From Washington Post:[end-div]

Go to Burning Man, and you’ll find everything from a thunderdome battle between a couple in tiger-striped bodypaint to a man dressed as a gigantic blueberry muffin on wheels. But underneath it all, says the festival’s co-founder, Larry Harvey, is “old-fashioned capitalism.”

There’s not a corporate logo in sight at the countercultural arts festival, and nothing is for sale but ice and coffee. But at its core, Harvey believes that Burning Man hews closely to the true spirit of a free-enterprise democracy: Ingenuity is celebrated, autonomy is affirmed, and self-reliance is expected. “If you’re talking about old-fashioned, Main Street Republicanism, we could be the poster child,” says Harvey, who hastens to add that the festival is non-ideological — and doesn’t anticipate being in GOP campaign ads anytime soon.

For more than two decades, the festival has funded itself entirely through donations and ticket sales — which now go up to $300 a pop — and it’s almost never gone in the red. And on the dry, barren plains of the Nevada desert where Burning Man materializes for a week each summer, you’re judged by what you do — your art, costumes and participation in a community that expects everyone to contribute in some form and frowns upon those who’ve come simply to gawk or mooch off others.

That’s part of the message that Harvey and his colleagues have brought to Washington this week, in his meetings with congressional staffers and the Interior Department to discuss the future of Burning Man. In fact, the festival is already a known quantity on the Hill: Harvey and his colleagues have been coming to Washington for years to explain the festival to policymakers, in least part because Burning Man takes place on public land that’s managed by the Interior Department.

In fact, Burning Man’s current challenge stems come because it’s so immensely popular, growing beyond 50,000 participants since it started some 20 years ago. “We’re no longer so taxed in explaining that it’s not a hippie debauch,” Harvey tells me over sodas in downtown Washington. “The word has leaked out so well that everyone now wants to come.” In fact, the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management that oversees the Black Rock Desert recently put the festival on probation for exceeding the land’s permitted crowd limits — a decision that organizers are now appealing.

Harvey now hopes to direct the enormous passion that Burning Man has stoked in its devotees over the years outside of Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, in the U.S. and overseas — the primary focus of this week’s visit to Washington. Last year, Burning Man transitioned from a limited liability corporation into a 501(c)3 nonprofit, which organizers believed was a better way to support their activities — not just for the festival, but for outside projects and collaborations in what festival-goers often refer to as “the default world.”

These days, Harvey — now in his mid-60s, dressed in a gray cowboy hat, silver western shirt, and aviator sunglasses — is just as likely to reference Richard Florida as the beatniks he once met on Haight Street. Most recently, he’s been talking with Tony Hsieh, the CEO of Zappos, who shares his vision of revitalizing Las Vegas, one of the cities hardest hit by the recent housing bust. “Urban renewal? We’re qualified. We’ve built up and torn down cities for 20 years,” says Harvey. “Cities everywhere are calling for artists, and it’s a blank slate there, blocks and blocks. … We want to extend the civil experiment — to see if business and art can coincide and not maim one another.”

Harvey points out that there’s been long-standing ties between Burning Man artists and to some of the private sector’s most successful executives. Its arts foundation, which distributes grants for festival projects, has received backing from everyone from real-estate magnate Christopher Bently to Mark Pincus, head of online gaming giant Zynga, as the Wall Street Journal points out. “There are a fair number of billionaires” who come to the festival every year, says Harvey, adding that some of the art is privately funded as well. In this way, Burning Man is a microcosm of San Francisco itself, stripping the bohemian artists and the Silicon Valley entrepreneurs of their usual tribal markers on the blank slate of the Nevada desert. At Burning Man, “when someone asks, ‘what do you do?’ — they meant, what did you just do” that day, he explains.

It’s one of the many apparent contradictions at the core of the festival: Paired with the philosophy of “radical self-reliance” — one that demands that participants cart out all their own food, water and shelter into a dust-filled desert for a week — is the festival’s communitarian ethos. Burning Man celebrates a gift economy that inspires random acts of generosity, and volunteer “rangers” traverse the festival to aid those in trouble. The climactic burning of the festival’s iconic “man”— along with a wooden temple filled with notes and memorials — is a ritual of togetherness and belonging for many participants. At the same time, one of the festival’s mottos is, ‘You have a right to hurt yourself.’ It’s the opposite of a nanny state,” Harvey says, recounting the time a participant unsuccessfully tried to sue the festival: He had walked out onto the coals after the “man”was set on fire and, predictably, burned himself.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

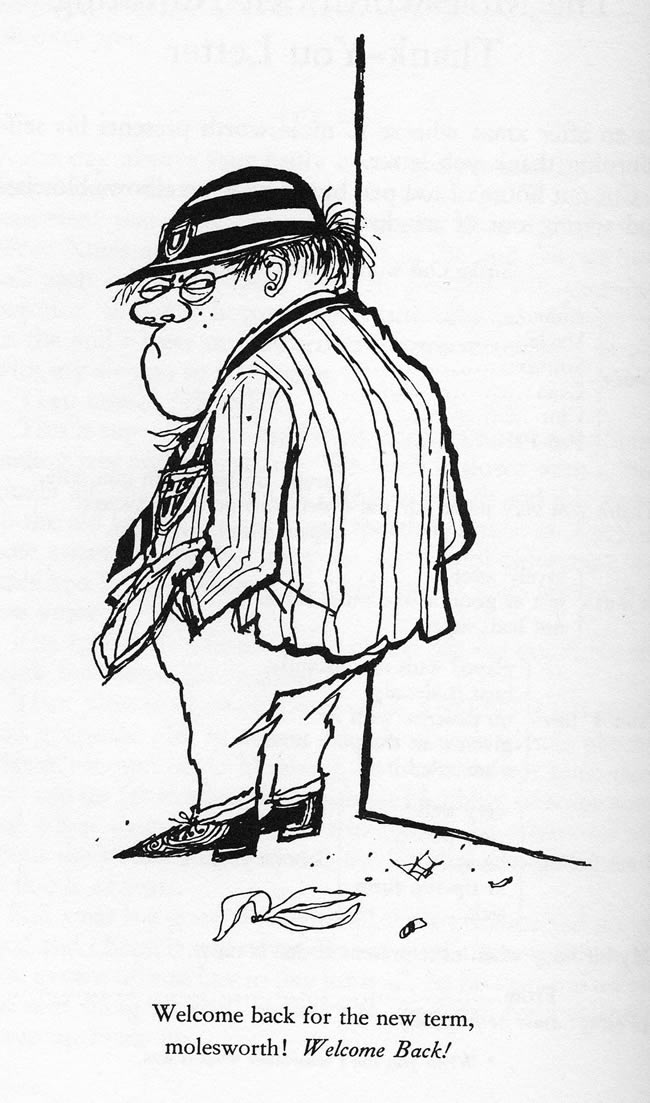

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Jailbreak.[end-div]

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,  [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

French children, it seems, unlike their cousins in the United States, don’t suffer temper tantrums, sit patiently at meal-times, defer to their parents, eat all their vegetables, respect adults, and are generally happy. Why is this and should American parents ditch the latest pop psychology handbooks for parenting lessons from La Belle France?

French children, it seems, unlike their cousins in the United States, don’t suffer temper tantrums, sit patiently at meal-times, defer to their parents, eat all their vegetables, respect adults, and are generally happy. Why is this and should American parents ditch the latest pop psychology handbooks for parenting lessons from La Belle France?

Once in a while a photographer comes along with a simple yet thoroughly new perspective. Japanese artist Photographer Hal fits this description. His images of young Japanese in a variety of contorted and enclosed situations are sometimes funny and disturbing, but certainly different and provocative.

Once in a while a photographer comes along with a simple yet thoroughly new perspective. Japanese artist Photographer Hal fits this description. His images of young Japanese in a variety of contorted and enclosed situations are sometimes funny and disturbing, but certainly different and provocative.

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen.

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen. Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?

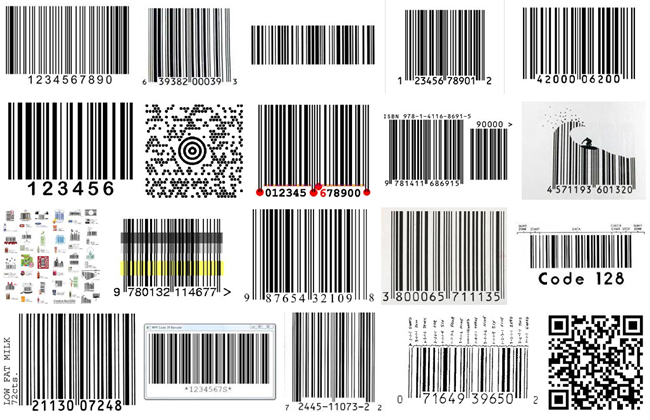

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?