Stories of people who risk life and limb to help a stranger and those who turn a blind eye are as current as they are ancient. Almost on a daily basis the 24-hours news cycle carries a heartwarming story of someone doing good to or for another; and seemingly just as often comes the story of indifference. Social and psychological researchers have studied this behavior in humans, and animals, for decades. However, only recently has progress been made in identifying some underlying factors. Peter Singer, a professor of bioethics at Princeton University, and researcher Agata Sagan recap some current understanding.

All of this leads to a conundrum: would it be ethical to market a “morality” pill that would make us do more good more often?

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

Last October, in Foshan, China, a 2-year-old girl was run over by a van. The driver did not stop. Over the next seven minutes, more than a dozen people walked or bicycled past the injured child. A second truck ran over her. Eventually, a woman pulled her to the side, and her mother arrived. The child died in a hospital. The entire scene was captured on video and caused an uproar when it was shown by a television station and posted online. A similar event occurred in London in 2004, as have others, far from the lens of a video camera.

Yet people can, and often do, behave in very different ways.

A news search for the words “hero saves” will routinely turn up stories of bystanders braving oncoming trains, swift currents and raging fires to save strangers from harm. Acts of extreme kindness, responsibility and compassion are, like their opposites, nearly universal.

Why are some people prepared to risk their lives to help a stranger when others won’t even stop to dial an emergency number?

Scientists have been exploring questions like this for decades. In the 1960s and early ’70s, famous experiments by Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo suggested that most of us would, under specific circumstances, voluntarily do great harm to innocent people. During the same period, John Darley and C. Daniel Batson showed that even some seminary students on their way to give a lecture about the parable of the Good Samaritan would, if told that they were running late, walk past a stranger lying moaning beside the path. More recent research has told us a lot about what happens in the brain when people make moral decisions. But are we getting any closer to understanding what drives our moral behavior?

Here’s what much of the discussion of all these experiments missed: Some people did the right thing. A recent experiment (about which we have some ethical reservations) at the University of Chicago seems to shed new light on why.

Researchers there took two rats who shared a cage and trapped one of them in a tube that could be opened only from the outside. The free rat usually tried to open the door, eventually succeeding. Even when the free rats could eat up all of a quantity of chocolate before freeing the trapped rat, they mostly preferred to free their cage-mate. The experimenters interpret their findings as demonstrating empathy in rats. But if that is the case, they have also demonstrated that individual rats vary, for only 23 of 30 rats freed their trapped companions.

The causes of the difference in their behavior must lie in the rats themselves. It seems plausible that humans, like rats, are spread along a continuum of readiness to help others. There has been considerable research on abnormal people, like psychopaths, but we need to know more about relatively stable differences (perhaps rooted in our genes) in the great majority of people as well.

Undoubtedly, situational factors can make a huge difference, and perhaps moral beliefs do as well, but if humans are just different in their predispositions to act morally, we also need to know more about these differences. Only then will we gain a proper understanding of our moral behavior, including why it varies so much from person to person and whether there is anything we can do about it.

[div class=attrib]Read more here.[end-div]

A group of new research studies show that our left- or right-handedness shapes our perception of “goodness” and “badness”.

A group of new research studies show that our left- or right-handedness shapes our perception of “goodness” and “badness”. Over the last 40 years or so physicists and cosmologists have sought to construct a single grand theory that describes our entire universe from the subatomic soup that makes up particles and describes all forces to the vast constructs of our galaxies, and all in between and beyond. Yet a major stumbling block has been how to bring together the quantum theories that have so successfully described, and predicted, the microscopic with our current understanding of gravity. String theory is one such attempt to develop a unified theory of everything, but it remains jumbled with many possible solutions and, currently, is beyond experimental verification.

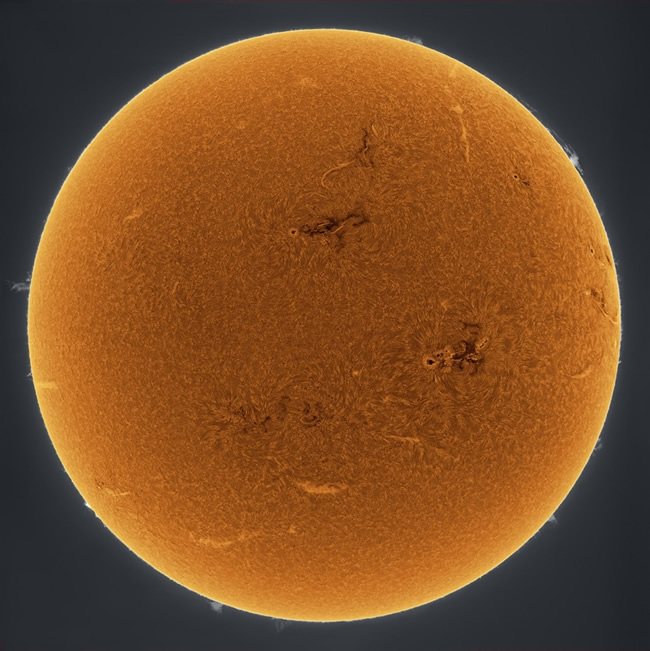

Over the last 40 years or so physicists and cosmologists have sought to construct a single grand theory that describes our entire universe from the subatomic soup that makes up particles and describes all forces to the vast constructs of our galaxies, and all in between and beyond. Yet a major stumbling block has been how to bring together the quantum theories that have so successfully described, and predicted, the microscopic with our current understanding of gravity. String theory is one such attempt to develop a unified theory of everything, but it remains jumbled with many possible solutions and, currently, is beyond experimental verification.

Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider.

Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider. As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”. Davide Castelvecchi over at Degrees of Freedom visits with one of the founding fathers of modern cosmology, Alan Guth.

Davide Castelvecchi over at Degrees of Freedom visits with one of the founding fathers of modern cosmology, Alan Guth. The world lost pioneering biologist Lynn Margulis on November 22.

The world lost pioneering biologist Lynn Margulis on November 22. Contemporary medical and surgical procedures have been completely transformed through the use of patient anaesthesia. Prior to the first use of diethyl ether as an anaesthetic in the United States in 1842, surgery, even for minor ailments, was often a painful process of last resort.

Contemporary medical and surgical procedures have been completely transformed through the use of patient anaesthesia. Prior to the first use of diethyl ether as an anaesthetic in the United States in 1842, surgery, even for minor ailments, was often a painful process of last resort.

Long before the first galaxy clusters and the first galaxies appeared in our universe, and before the first stars, came the first basic elements — hydrogen, helium and lithium.

Long before the first galaxy clusters and the first galaxies appeared in our universe, and before the first stars, came the first basic elements — hydrogen, helium and lithium.

In early 2010 a Japanese research team grew retina-like structures from a culture of mouse embryonic stem cells. Now, only a year later, the same team at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology announced their success in growing a much more complex structure following a similar process — a mouse pituitary gland. This is seen as another major step towards bioengineering replacement organs for human transplantation.

In early 2010 a Japanese research team grew retina-like structures from a culture of mouse embryonic stem cells. Now, only a year later, the same team at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology announced their success in growing a much more complex structure following a similar process — a mouse pituitary gland. This is seen as another major step towards bioengineering replacement organs for human transplantation. [div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div] We promise. There is no screeching embedded audio of someone slowly dragging a piece of chalk, or worse, fingernails, across a blackboard! Though, even the thought of this sound causes many to shudder. Why? A plausible explanation over at Wired UK.

We promise. There is no screeching embedded audio of someone slowly dragging a piece of chalk, or worse, fingernails, across a blackboard! Though, even the thought of this sound causes many to shudder. Why? A plausible explanation over at Wired UK.

The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was recently awarded to three scientists: Adam Riess, Saul Perlmutter and Brian Schmidt. Their computations and observations of a very specific type of exploding star upended decades of commonly accepted beliefs of our universe. Namely, that the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was recently awarded to three scientists: Adam Riess, Saul Perlmutter and Brian Schmidt. Their computations and observations of a very specific type of exploding star upended decades of commonly accepted beliefs of our universe. Namely, that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. Would you like to know when you will die?

Would you like to know when you will die?

The world of particle physics is agog with recent news of an experiment that shows a very unexpected result – sub-atomic particles traveling faster than the speed of light. If verified and independently replicated the results would violate one of the universe’s fundamental properties described by Einstein in the Special Theory of Relativity. The speed of light — 186,282 miles per second (299,792 kilometers per second) — has long been considered an absolute cosmic speed limit.

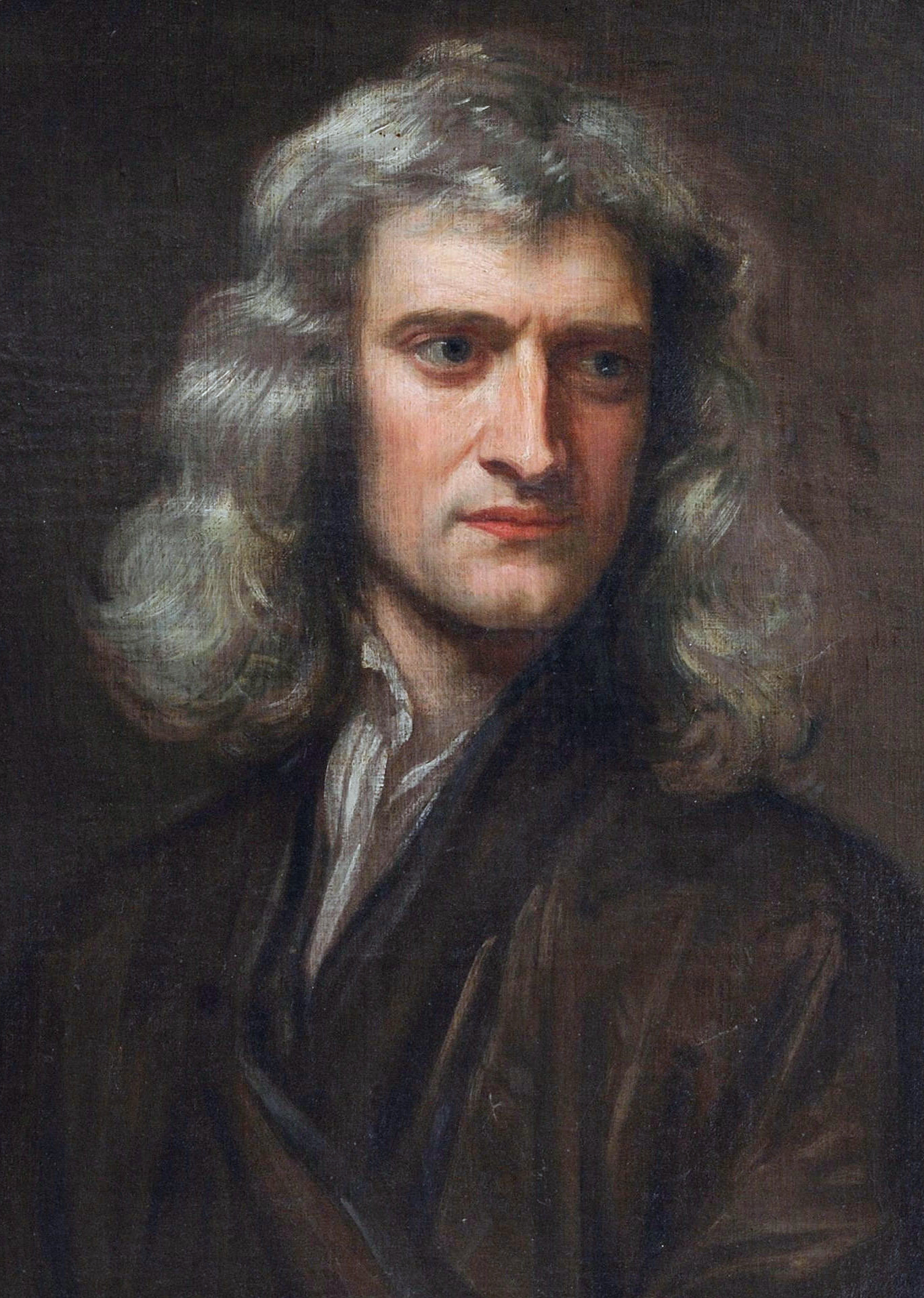

The world of particle physics is agog with recent news of an experiment that shows a very unexpected result – sub-atomic particles traveling faster than the speed of light. If verified and independently replicated the results would violate one of the universe’s fundamental properties described by Einstein in the Special Theory of Relativity. The speed of light — 186,282 miles per second (299,792 kilometers per second) — has long been considered an absolute cosmic speed limit. Aside from founding classical mechanics — think universal gravitation and laws of motion, laying the building blocks of calculus, and inventing the reflecting telescope Isaac Newton made time for spiritual pursuits. In fact, Newton was a highly religious individual (though a somewhat unorthodox Christian).

Aside from founding classical mechanics — think universal gravitation and laws of motion, laying the building blocks of calculus, and inventing the reflecting telescope Isaac Newton made time for spiritual pursuits. In fact, Newton was a highly religious individual (though a somewhat unorthodox Christian).