Over the coming years the words “Thwaites Glacier” will become known to many people, especially those who make their home near the world’s oceans. The thawing of Antarctic ice and the accelerating melting of its glaciers — of which Thwaites is a prime example — pose an increasing threat to our coasts, but imperil us all.

Thwaites is one of size mega-glaciers that drain into the West Antarctic’s Amundsen Sea. If all were to melt completely, as they are continuing to do, global sea-level would be projected to rise an average of 4½ feet. Astonishingly, this catastrophe in the making has passed a tipping-point — climatologists and glaciologists now tend to agree that the melting is irreversible and accelerating.

From ars technica:

Today, researchers at UC Irvine and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory have announced results indicating that glaciers across a large area of West Antarctica have been destabilized and that there is little that will stop their continuing retreat. These glaciers are all that stand between the ocean and a massive basin of ice that sits below sea level. Should the sea invade this basin, we’d be committed to several meters of sea level rise.

Even in the short term, the new findings should increase our estimates for sea level rise by the end of the century, the scientists suggest. But the ongoing process of retreat and destabilization will mean that the area will contribute to rising oceans for centuries.

The press conference announcing these results is ongoing. We will have a significant update on this story later today.

UPDATE (2:05pm CDT):

The glaciers in question are in West Antarctica, and drain into the Amundsen Sea. On the coastal side, the ends of the glacier are actually floating on ocean water. Closer to the coast, there’s what’s called a “grounding line,” where the weight of the ice above sea level pushes the bottom of the glacier down against the sea bed. From there on, back to the interior of Antarctica, all of the ice is directly in contact with the Earth.

That’s a rather significant fact, given that, just behind a range of coastal hills, all of the ice is sitting in a huge basin that’s significantly below sea level. In total, the basin contains enough ice to raise sea levels approximately four meters, largely because the ice piled in there rises significantly above sea level.

Because of this configuration, the grounding line of the glaciers that drain this basin act as a protective barrier, keeping the sea back from the base of the deeper basin. Once ocean waters start infiltrating the base of a glacier, the glacier melts, flows faster, and thins. This lessens the weight holding the glacier down, ultimately causing it to float, which hastens its break up. Since the entire basin is below sea level (in some areas by over a kilometer), water entering the basin via any of the glaciers could destabilize the entire thing.

Thus, understanding the dynamics of the grounding lines is critical. Today’s announcements have been driven by two publications. One of them models the behavior of one of these glaciers, and shows that it has likely reached a point where it will be prone to a sudden retreat sometime in the next few centuries. The second examines every glacier draining this basin, and shows that all but one of them are currently losing contact with their grounding lines.

Ungrounded

The data come from two decades worth of data from the ESA’s Earth Remote Sensing satellites. These include radar that performs two key functions: peers through the ice to get a sense of the terrain that lies buried under the ice near the grounding line. And, through interferometry, it tracks the dynamics of the ice sheet’s flow in the area, as well as its thinning and the location of the grounding line itself. The study tracks a number of glaciers that all drain into the region: Pine Island, Thwaites, Haynes, and Smith/Kohler.

As we’ve covered previously, the Pine Island Glacier came ungrounded in the second half of the past decade, retreating up to 31km in the process. Although this was the one that made headlines, all the glaciers in the area are in retreat. Thwaites saw areas retreat up to 14km over the course of the study, Haynes retracted by 10km, and the Smith/Kohler glaciers retreated by 35km.

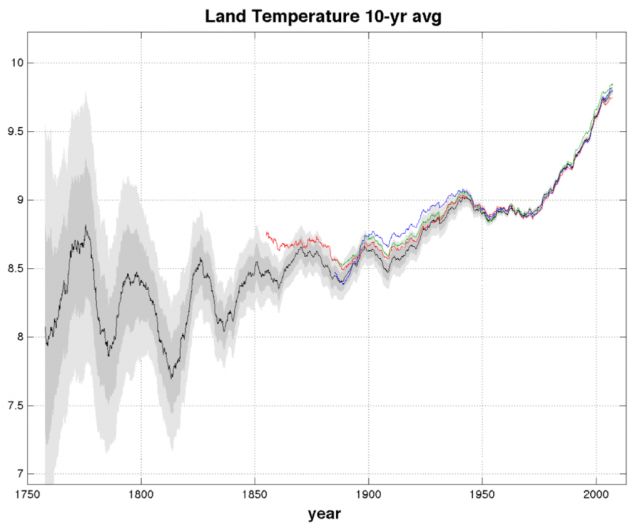

The retreating was accompanied by thinning of the glaciers, as ice that had been held back above sea levels in the interior spread forward and thinned out. This contributed to sea level rise, and the speakers at the press conference agreed that the new data shows that the recently released IPCC estimates for sea level rise are out of date; even by the end of this century, the continuation of this process will significantly increase the rate of sea level rise we can expect.

The real problem, however, comes later. Glaciers can establish new grounding lines if there’s a feature in the terrain, such as a hill that rises above sea level, that provides a new anchoring point. The authors see none: “Upstream of the 2011 grounding line positions, we find no major bed obstacle that would prevent the glaciers from further retreat and draw down the entire basin.” In fact, several of the existing grounding lines are close to points where the terrain begins to slope downward into the basin.

For some of the glaciers, the problems are already starting. At Pine Island, the bottom of the glacier is now sitting on terrain that’s 400 meters deeper than where the end rested in 1992, and there are no major hills between there and the basin. As far as the Smith/Kohler glaciers, the grounding line is 800 meters deeper and “its ice shelf pinning points are vanishing.”

What’s next?

As a result, the authors concluded that these glaciers are essentially destabilized—unless something changes radically, they’re destined for retreat into the indefinite future. But what will the trajectory of that retreat look like? In this case, the data doesn’t directly help. It needs to be fed into a model that projects the current melting into the future. Conveniently, a different set of scientists has already done this modeling.

The work focuses on the Thwaites glacier, which appears to be the most stable: there are 60-80km before between the existing terminus and the deep basin, and two or three ridges within that distance that will allow the formation of new grounding lines.

The authors simulated the behavior of Thwaites using a number of different melting rates. These ranged from a low that approximated the behavior typical in the early 90s, to a high rate of melt that is similar to what was observed in recent years. Every single one of these situations saw the Thwaites retreat into the deep basin within the next 1,000 years. In the higher melt scenarios—the ones most reflective of current conditions—this typically took only a few centuries.

The other worrisome behavior is that there appeared to be a tipping point. In every simulation that saw an extensive retreat, rates of melting shifted from under 80 gigatonnes of ice per year to 150 gigatonnes or more, all within the span of a couple of decades. In the later conditions, this glacier alone contributed half a centimeter to sea level rise—every year.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Thwaites Glacier, Antarctica, 2012. Courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory.

New research models show just how precarious our planet’s climate really is. Runaway greenhouse warming would make a predicted 2-6 feet rise in average sea levels over the next 50-100 years seem like a puddle at the local splash pool.

New research models show just how precarious our planet’s climate really is. Runaway greenhouse warming would make a predicted 2-6 feet rise in average sea levels over the next 50-100 years seem like a puddle at the local splash pool. Yesterday, May 10, 2013, scientists published new measures of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). For the first time in human history CO2 levels reached an average of 400 parts per million (ppm). This is particularly troubling since CO2 has long been known as the most potent heat trapping component of the atmosphere. The sobering milestone was recorded from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii — monitoring has been underway at the site since the mid-1950s.

Yesterday, May 10, 2013, scientists published new measures of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). For the first time in human history CO2 levels reached an average of 400 parts per million (ppm). This is particularly troubling since CO2 has long been known as the most potent heat trapping component of the atmosphere. The sobering milestone was recorded from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii — monitoring has been underway at the site since the mid-1950s. It’s no surprise that in our daily lives we seek information that reinforces our perceptions, opinions and beliefs of the world around us. It’s also the case that if we do not believe in a particular position, we will overlook any evidence in our immediate surroundings that runs contrary to our disbelief — climate change is no different.

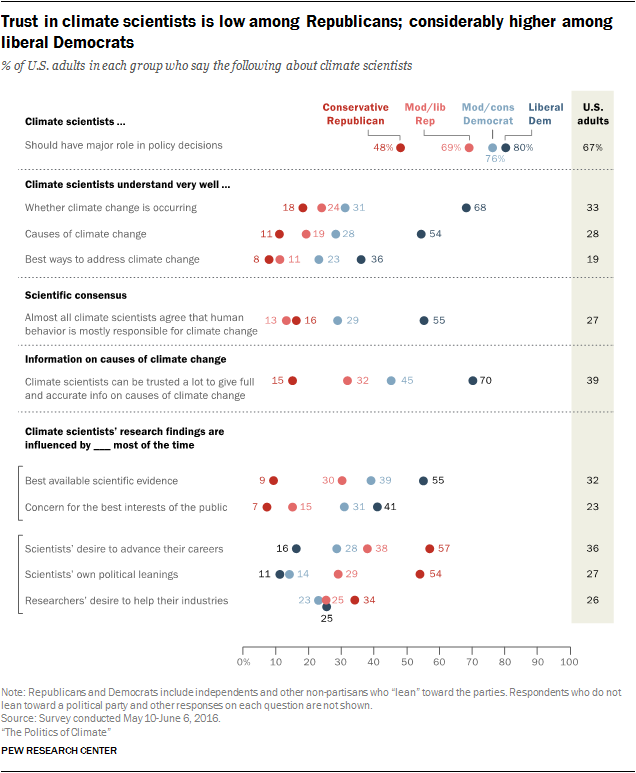

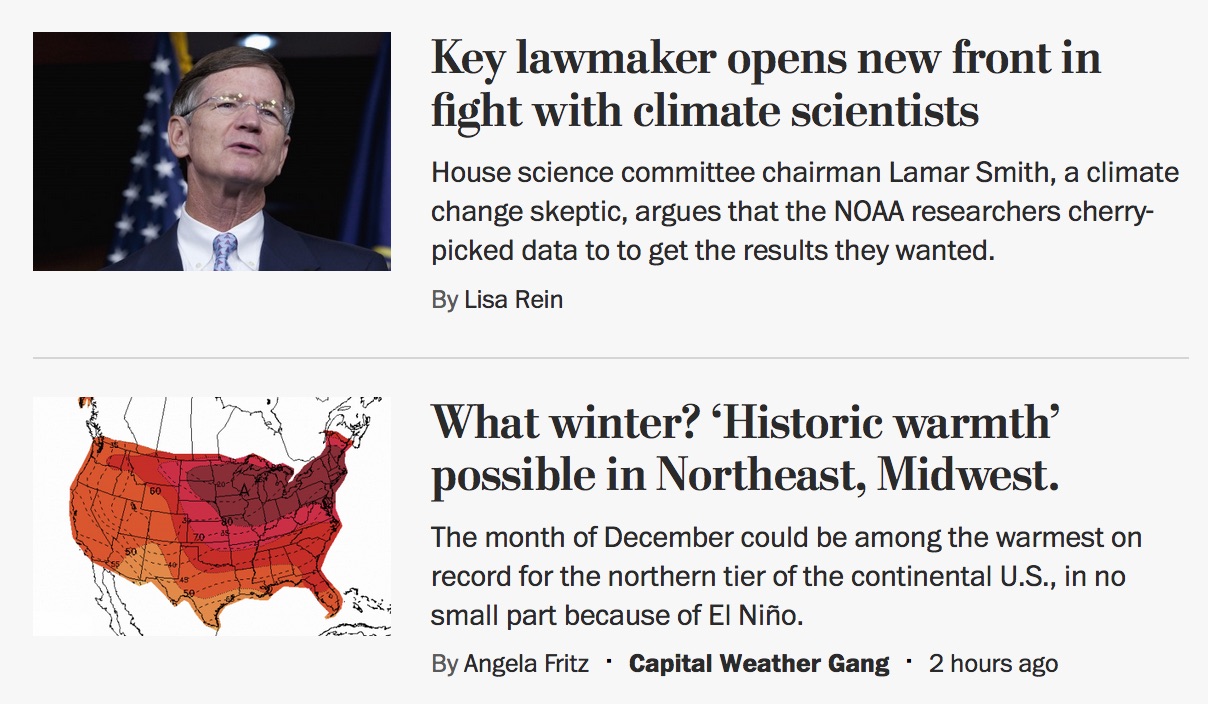

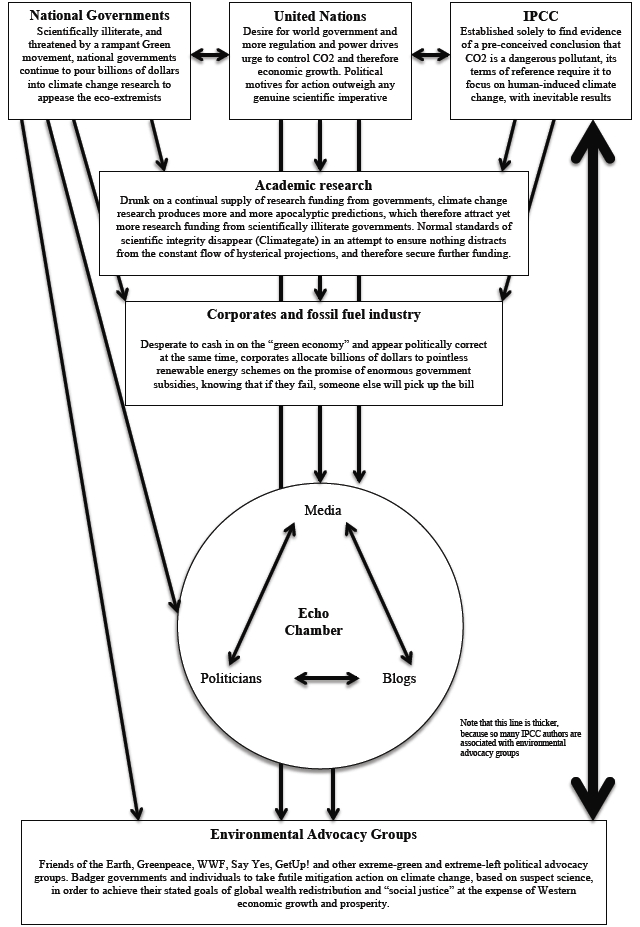

It’s no surprise that in our daily lives we seek information that reinforces our perceptions, opinions and beliefs of the world around us. It’s also the case that if we do not believe in a particular position, we will overlook any evidence in our immediate surroundings that runs contrary to our disbelief — climate change is no different. Why study the science of climate change when you can study the complexities of climate change deniers themselves? That was the question that led several groups of independent researchers to study why some groups of people cling to mistaken beliefs and hold inaccurate views of the public consensus.

Why study the science of climate change when you can study the complexities of climate change deniers themselves? That was the question that led several groups of independent researchers to study why some groups of people cling to mistaken beliefs and hold inaccurate views of the public consensus.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

While scientific evidence of climate change continues to mount and an increasing number of studies point causal fingers at ourselves there is perhaps another way to visualize the risk of inaction or over-reaction. So, since most people can leave ideology aside when it comes to their own health, a medical metaphor, courtesy of Andrew Revkin over at Dot Earth, may be of use to broaden acceptance of the message.

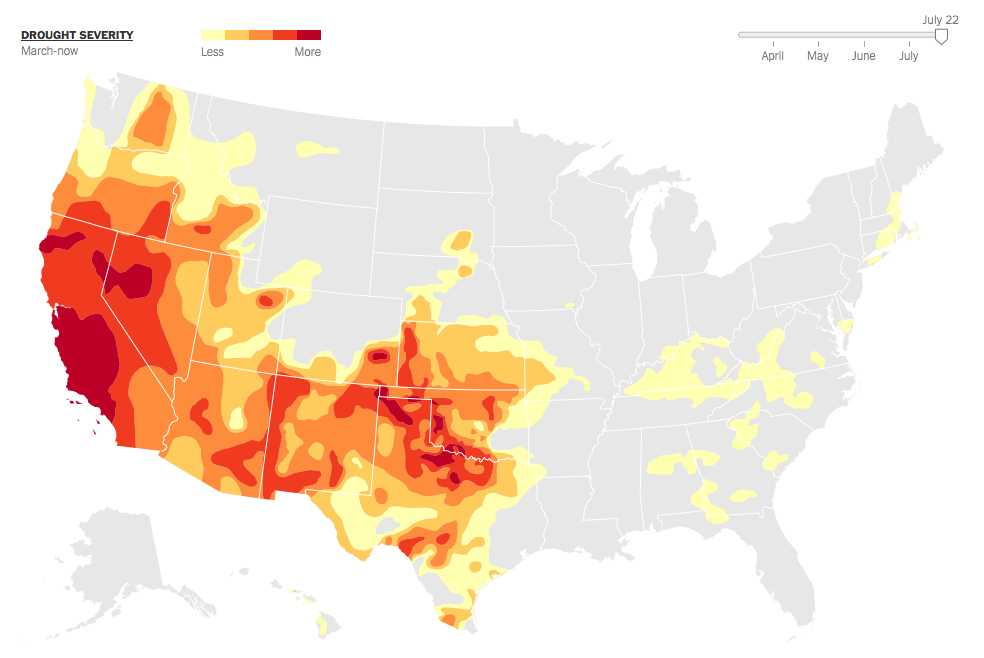

While scientific evidence of climate change continues to mount and an increasing number of studies point causal fingers at ourselves there is perhaps another way to visualize the risk of inaction or over-reaction. So, since most people can leave ideology aside when it comes to their own health, a medical metaphor, courtesy of Andrew Revkin over at Dot Earth, may be of use to broaden acceptance of the message. It’s #$% hot in the southern plains of the United States, with high temperatures constantly above 100 degrees F, and lows never dipping below 80. For that matter, it’s hotter than average this year in most parts of the country. So, a timely article over at Slate gives a great overview of the history of the air conditioning system, courtesy of inventor Willis Carrier.

It’s #$% hot in the southern plains of the United States, with high temperatures constantly above 100 degrees F, and lows never dipping below 80. For that matter, it’s hotter than average this year in most parts of the country. So, a timely article over at Slate gives a great overview of the history of the air conditioning system, courtesy of inventor Willis Carrier. [div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div]