The boss of Netflix, Ted Sarandos, is planning to kill you, with kindness. Actually, joy. His plan to recast our consumption of television programming aims to deliver mountains of joyful entertainment in place of the current wasteland of incremental TV-dross punctuated with schlock-TV.

The boss of Netflix, Ted Sarandos, is planning to kill you, with kindness. Actually, joy. His plan to recast our consumption of television programming aims to deliver mountains of joyful entertainment in place of the current wasteland of incremental TV-dross punctuated with schlock-TV.

While the plan is still in work, the fruits of Netflix’s labor are becoming apparent — binge-watching is rapidly assuming the momentum of a cultural wave in the US. The super-sized viewing gulp, from say thirteen successive hours of House of Cards or Orange is the New Black, is quickly replacing the national attention deficit disorder enabled by the once anxious and restless trigger finger on the TV-remote, as viewers flip from one mindless show to the next. Yet, by making Netflix into the next great media and entertainment empire Sarandos may be laying the foundation for an unintended, and more important, benefit — lengthening the attention-span of the average adult.

From the Guardian:

Is Ted Sarandos a force for evil? It’s a theory. Consider the evidence. Britain is already a country beset by various health-ruining, bank balance-depleting behaviours – binge-drinking, chain-smoking, overeating, watching football. Since January 2012 when Netflix launched its UK operation, Sarandos, its chief content officer, has created a new demographic of bingeing Britons –1.5 million subscribers who spend £5.99 a month to gorge on TV online.

To get a sense of what the 49-year-old Arizonan is doing to TV culture, imagine that you’ve just finished watching episode five of Joss Whedon’s Firefly on your laptop, courtesy of Netflix. You’ve got places to go, people to meet. But up pops a little box on screen saying the next episode starts in 12 seconds. Five hours later, you dimly realise that you’ve forgotten to pick up your kids from school and/or your boss has texted you 12 times wondering if you’re planning to show up today.

Dooes he feel responsible for creating this binge culture, not just here but across the world (Netflix has 38 million subscribers in 40 countries, who watch about a billion hours of TV shows and films each month), I ask Sarandos when we meet in a London hotel? He laughs. “I love it when it happens that you just have to watch. It only takes that little bit of prodding.”

Sarandos feels it is legitimate to prod the audience so that they can get what they want. Or what he thinks they want. All 13 episodes of, say, political thriller House of Cards with Kevin Spacey, or the same number of prison comedy drama Orange is the New Black with Taylor Schilling, released in one great virtual lump.

Why? “The television business is based on managed dissatisfaction. You’re watching a great television show you’re really wrapped up in? You might get 50 minutes of watching a week and then 18,000 minutes of waiting until the next episode comes along. I’d rather make it all about the joy.”

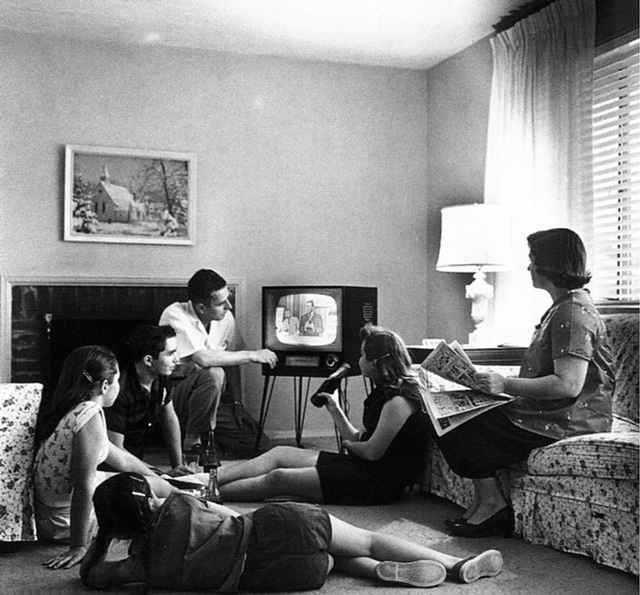

Sarandos says he got an intimation of the pleasures of binge-viewing as a teenager in Phoenix, Arizona. On Sundays in the mid-70s, he and his family would gather round the telly to watch Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, a satire on soap operas. “If you worked, the only way could catch up with the five episodes they showed in the week was watching them back to back on Sunday night. So bingeing was already big in my subconscious.”

Years later, Sarandos binged again. “I really loved the Sopranos but didn’t have HBO. So someone would send me tapes of the show with three or four episodes. I would watch one episode and go: ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to watch one more.’ I’d watch the whole tape and champ at the bit for the next one.”

The TV revolution for which Sarandos and Netflix are responsible involves eliminating bit-champing and monetising instant gratification. Netflix has done well from that revolution: its reported net income was $29.5m for the quarter ending 30 June. Profits quintupled compared with the same period in 2012 – in part due to its new UK operation.

Sarandos hasn’t done badly either. He and his wife, former US ambassador Nicole Avant, have a $5.4m Beverly Hills property and recently bought comedian David Spade’s beachside Malibu home for $10.2m. Sarandos argues viewers have long been battling schedulers bent on stopping them seeing what they want, when they want. “Before time shifting, they would use VCRs to collect episodes and view them whenever they wanted. And, more importantly, in whatever doses they wanted. Then DVD box sets and later DVRs made that self-dosing even more sophisticated.”

He began studying how viewers consumed TV while working part-time in a strip-mall video store in the early 1980s. By 30, he was an executive for a company supplying Blockbuster with videos. In 2000, he was hired by Netflix to develop its service posting rental DVDs to customers. “We saw that people would return those discs for TV series very quickly, given they had three hours of programming on them – more quickly than they would a movie. They wanted the next hit.”

Netflix mutated from a DVD-by-post service to an on-demand internet network for films and TV series, and Sarandos found himself cutting deals with traditional TV networks to broadcast shows online a season after they were originally shown, instead of waiting for several years for them to be available for syndication.

Thanks to Netflix and its competitors, the old TV set in the living room is becoming redundant. That living-room fixture has been replaced by a host of mobile surrogates – tablet, laptop, Xbox and even smart phone.

Were that all Sarandos had achieved, he would have been minor player in the idiot box revolution. But a couple of years ago, he decided Netflix should commission its own drama series and release them globally in season-sized bundles. In making that happen, he radically changed not just how but what we watch.

Why bother? “Up till a couple of years ago, a network would make every pilot for a series into a one-off show. I started getting worried, thinking nobody’s going to make series any more, and so we wouldn’t be able to buy them [for Netflix] a season after they’ve been broadcast. So we said maybe we should develop that muscle ourselves.” Sarandos has a $2bn annual content budget, and spends as much as 10% on developing that muscle.

Strikingly, he didn’t spend that money on movies, but TV. Why? “Movies are becoming more global, which is making them less intimate. If you make a movie for the world, you don’t make it for any country.

“I think television is going in the opposite direction – richer characterisation, denser storylines – and so much more like reading a novel. It is a golden age for TV, but only because the best writers and directors increasingly like to work outside Hollywood.” Hence, perhaps, the successes of The Sopranos, The West Wing, The Wire, Downton Abbey, and by this time next year – he hopes – Netflix series such as the Wachowskis’ sci-fi drama Sense 8. TV, if Sarandos has his way, is the new Hollywood.

Netflix’s first foray into original drama came only last year with Lilyhammer, in which Steve Van Zandt, who played mobster Silvio Dante in The Sopranos, reprised his gangster chops as Frank “The Fixer” Tagliano, a mobster starting a new life in Lillehammer, Norway. The whole season of eight episodes was released on Netflix at the same time, delighting those suffering withdrawal symptoms after the end of The Sopranos. A second season is soon to be released.

Sarandos suggests Lilyhammer points the way to a new globalised future for TV drama – more than a fifth of Norway’s population watched the show. “It opened a world of possibilities – mainstream viewing of subtitled programming in the US and releasing in every language and every territory at the exact same moment. To me, that’s what the future will be like.”

Sarandos also tore up another page of the TV rulebook, the one that says each episode of a series must be the same length. “If you watched Arrested Development [the sitcom he recommissioned in May, seven years after it last broadcast] none of those episodes has the same running time – some were 28 minutes, some 47 minutes. I’m saying take as much time as you need to tell the story well. You couldn’t really do that on linear television because you have a grid, commercial breaks and the like.”

House of Cards, his second commissioned drama series whose first season was released in February, even better demonstrates Sarandos’s diabolical genius (if that is what it is). He once described himself as “a human algorithm” for his ability, developed in that Phoenix strip mall, for recommending movies based on a customer’s previous rentals. He did something similar when he commissioned House of Cards.

“It was generated by algorithm,” Sarandos says, grinning. But he’s not entirely joking. “I didn’t use data to make the show, but I used data to determine the potential audience to a level of accuracy very few people can do.”

It worked like this. In 2011, he learned that Hollywood director David Fincher, then working on his movie adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, was pitching his first TV series. Based on a script by Oscar-nominated writer Beau Willimon, it was to be a remake the 1990 BBC series House of Cards, and would star Kevin Spacey as an amoral US senator.

Some networks were sceptical, but Sarandos – not least because he’s a political junkie who loves political thrillers and, along with his wife, helped raise nearly $700m for Obama’s re-election campaign – was tempted. He unleashed his spreadsheets, using Netflix data to determine how many subscribers watched political dramas such as The West Wing or the original House of Cards.

“We’ve been collecting data for a long time. It showed how many Netflix members love The West Wing and the original House of Cards. It also showed who loved David Fincher’s films and Kevin Spacey’s.”

Armed with this data, Sarandos made the biggest gamble of his life. He went to David Fincher’s West Hollywood office and announced he wanted to spend $100m on not one, but two 13-part seasons of House of Cards. Based on his calculations, he says: “I felt that sounded like a pretty safe bet.”

Read the entire article here.

Image: Netflix logo. Courtesy of Wikipedia / Netflix.

In almost 90 years since television was invented it has done more to re-shape our world than conquering armies and pandemics. Whether you see TV as a force for good or evil — or more recently, as a method for delivering absurd banality — you would be hard-pressed to find another human invention that has altered us so profoundly, psychologically, socially and culturally. What would its creator — John Logie Baird — think of his invention now, almost 70 years after his death?

In almost 90 years since television was invented it has done more to re-shape our world than conquering armies and pandemics. Whether you see TV as a force for good or evil — or more recently, as a method for delivering absurd banality — you would be hard-pressed to find another human invention that has altered us so profoundly, psychologically, socially and culturally. What would its creator — John Logie Baird — think of his invention now, almost 70 years after his death? Robert Hof argues that the time is ripe for Steve Jobs’ corporate legacy to reinvent the TV. Apple transformed the personal computer industry, the mobile phone market and the music business. Clearly the company has all the components in place to assemble another innovation.

Robert Hof argues that the time is ripe for Steve Jobs’ corporate legacy to reinvent the TV. Apple transformed the personal computer industry, the mobile phone market and the music business. Clearly the company has all the components in place to assemble another innovation.

A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes,

A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes,