A week ago, on July 4, 2012 researchers at CERN told the world that they had found evidence of a new fundamental particle — the so-called Higgs boson, or something closely similar. If further particle collisions at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider uphold this finding over the coming years, this will rank as significant a discovery as that of the proton or the electro-magnetic force. While practical application of this discovery, in our lifetimes at least, is likely to be scant, it undeniably furthers our quest to understand the underlying mechanism of our existence.

So where might this discovery lead next?

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

“As a layman, I would say, I think we have it,” said Rolf-Dieter Heuer, director general of CERN at Wednesday’s seminar announcing the results of the search for the Higgs boson. But when pressed by journalists afterwards on what exactly “it” was, things got more complicated. “We have discovered a boson – now we have to find out what boson it is,” he said cryptically. Eh? What kind of particle could it be if it isn’t the Higgs boson? And why would it show up right where scientists were looking for the Higgs? We asked scientists at CERN to explain.

If we don’t know the new particle is a Higgs, what do we know about it?

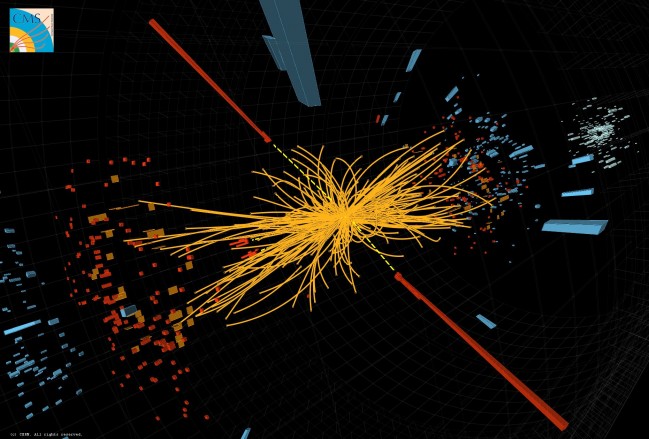

We know it is some kind of boson, says Vivek Sharma of CMS, one of the two Large Hadron Collider experiments that presented results on Wednesday. There are only two types of elementary particle in the standard model: fermions, which include electrons, quarks and neutrinos, and bosons, which include photons and the W and Z bosons. The Higgs is a boson – and we know the new particle is too because one of the things it decays into is a pair of high-energy photons, or gamma rays. According to the rules of mathematical symmetry, only a boson could decay into exactly two other photons.

Anything else?

Another thing we can say about the new particle is that nothing yet suggests it isn’t a Higgs. The standard model, our leading explanation for the known particles and the forces that act on them, predicts the rate at which a Higgs of a given mass should decay into various particles. The rates of decay reported for the new particle yesterday are not exactly what would be predicted for its mass of about 125 gigaelectronvolts (GeV) – leaving the door open to more exotic stuff. “If there is such a thing as a 125 GeV Higgs, we know what its rate of decay should be,” says Sharma. But the decay rates are close enough for the differences to be statistical anomalies that will disappear once more data is taken. “There are no serious inconsistencies,” says Joe Incandela, head of CMS, who reported the results on Wednesday.

In that case, are the CERN scientists just being too cautious? What would be enough evidence to call it a Higgs boson?

As there could be many different kinds of Higgs bosons, there’s no straight answer. An easier question to answer is: what would make the new particle neatly fulfil the Higgs boson’s duty in the standard model? Number one is to give other particles mass via the Higgs field – an omnipresent entity that “slows” some particles down more than others, resulting in mass. Any particle that makes up this field must be “scalar”. The opposite of a vector, this means that, unlike a magnetic field, or gravity, it doesn’t have any directionality. “Only a scalar boson fixes the problem,” says Oliver Buchmueller, also of CMS.

When will we know whether it’s a scalar boson?

By the end of the year, reckons Buchmueller, when at least one outstanding property of the new particle – its spin – should be determined. Scalars’ lack of directionality means they have spin 0. As the particle is a boson, we already know its spin is a whole number and as it decays into two photons, mathematical symmetry again dictates that the spin can’t be 1. Buchmueller says LHC researchers will able to determine whether it has a spin of 0 or 2 by examining whether the Higgs’ decay particles shoot into the detector in all directions or with a preferred direction – the former would suggest spin 0. “Most people think it is a scalar, but it still needs to be proven,” says Buchmueller. Sharma is pretty sure it’s a scalar boson – that’s because it is more difficult to make a boson with spin 2. He adds that, although it is expected, confirmation that this is a scalar boson is still very exciting: “The beautiful thing is, if this turns out to be a scalar particle, we are seeing a new kind of particle. We have never seen a fundamental particle that is a scalar.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: A typical candidate event including two high-energy photons whose energy (depicted by dashed yellow lines and red towers) is measured in the CMS electromagnetic calorimeter. The yellow lines are the measured tracks of other particles produced in the collision.[end-div]