Author Andrew Keen ponders the true value of the internet in his new book The Internet is Not the Answer. Quite rightfully he asserts that many billions of consumers have benefited from the improved convenience and usually lower prices of every product imaginable delivered through a couple of clicks online. But there is a higher price to pay — one that touches on the values we want for our society and the deeper costs to our culture.

From the Guardian:

During every minute of every day of 2014, according to Andrew Keen’s new book, the world’s internet users – all three billion of them – sent 204m emails, uploaded 72 hours of YouTube video, undertook 4m Google searches, shared 2.46m pieces of Facebook content, published 277,000 tweets, posted 216,000 new photos on Instagram and spent $83,000 on Amazon.

By any measure, for a network that has existed recognisably for barely 20 years (the first graphical web browser, Mosaic, was released in 1993), those are astonishing numbers: the internet, plainly, has transformed all our lives, making so much of what we do every day – communicating, shopping, finding, watching, booking – unimaginably easier than it was. A Pew survey in the United States found last year that 90% of Americans believed the internet had been good for them.

So it takes a brave man to argue that there is another side to the internet; that stratospheric numbers and undreamed-of personal convenience are not the whole story. Keen (who was once so sure the internet was the answer that he sank all he had into a startup) is now a thoughtful and erudite contrarian who believes the internet is actually doing untold damage. The net, he argues, was meant to be “power to the people, a platform for equality”: an open, decentralised, democratising technology that liberates as it empowers as it informs.

Instead, it has handed extraordinary power and wealth to a tiny handful of people, while simultaneously, for the rest of us, compounding and often aggravating existing inequalities – cultural, social and economic – whenever and wherever it has found them. Individually, it may work wonders for us. Collectively, it’s doing us no good at all. “It was supposed to be win-win,” Keen declares. “The network’s users were supposed to be its beneficiaries. But in a lot of ways, we are its victims.”

This is not, Keen acknowledges, a very popular view, especially in Silicon Valley, where he has spent the best part of the past 30-odd years after an uneventful north London childhood (the family was in the rag trade). But The Internet is Not the Answer – Keen’s third book (the first questioned the value of user-generated content, the second the point of social media; you get where he’s coming from) – has been “remarkably well received”, he says. “I’m not alone in making these points. Moderate opinion is starting to see that this is a problem.”

What seems most unarguable is that, whatever else it has done, the internet – after its early years as a network for academics and researchers from which vulgar commercial activity was, in effect, outlawed – has been largely about the money. The US government’s decision, in 1991, to throw the nascent network open to private enterprise amounted, as one leading (and now eye-wateringly wealthy) Californian venture capitalist has put it, to “the largest creation of legal wealth in the history of the planet”.

The numbers Keen reels off are eye-popping: Google, which now handles 3.5bn searches daily and controls more than 90% of the market in some countries, including Britain, was valued at $400bn last year – more than seven times General Motors, which employs nearly four times more people. Its two founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, are worth $30bn apiece. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, head of the world’s second biggest internet site – used by 19% of people in the world, half of whom access it six days a week or more – is sitting on a similar personal pile, while at $190bn in July last year, his company was worth more than Coca-Cola, Disney and AT&T.

Jeff Bezos of Amazon also has $30bn in his bank account. And even more recent online ventures look to be headed the same way: Uber, a five-year-old startup employing about 1,000 people and once succinctly described as “software that eats taxis”, was valued last year at more than $18bn – roughly the same as Hertz and Avis combined. The 700-staff lodging rental site Airbnb was valued at $10bn in February last year, not far off half as much as the Hilton group, which owns nearly 4,000 hotels and employs 150,000 people. The messaging app WhatsApp, bought by Facebook for $19bn, employs just 55, while the payroll of Snapchat – which turned down an offer of $3bn – numbers barely 20.

Part of the problem here, argues Keen, is that the digital economy is, by its nature, winner-takes-all. “There’s no inevitable or conspiratorial logic here; no one really knew it would happen,” he says. “There are just certain structural qualities that mean the internet lends itself to monopolies. The internet is a perfect global platform for free-market capitalism – a pure, frictionless, borderless economy … It’s a libertarian’s wet dream. Digital Milton Friedman.”Nor are those monopolies confined to just one business. Keen cites San Francisco-based writer Rebecca Solnit’s incisive take on Google: imagine it is 100 years ago, and the post office, the phone company, the public libraries, the printing houses, Ordnance Survey maps and the cinemas were all controlled by the same secretive and unaccountable organisation. Plus, he adds, almost as an afterthought: “Google doesn’t just own the post office – it has the right to open everyone’s letters.”

This, Keen argues, is the net economy’s natural tendency: “Google is the search and information monopoly and the largest advertising company in history. It is incredibly strong, joining up the dots across more and more industries. Uber’s about being the transport monopoly; Airbnb the hospitality monopoly; TaskRabbit the labour monopoly. These are all, ultimately, monopoly plays – that’s the logic. And that should worry people.”

It is already having consequences, Keen says, in the real world. Take – surely the most glaring example – Amazon. Keen’s book cites a 2013 survey by the US Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which found that while it takes, on average, a regular bricks-and-mortar store 47 employees to generate $10m in turnover, Bezos’s many-tentacled, all-consuming and completely ruthless “Everything Store” achieves the same with 14. Amazon, that report concluded, probably destroyed 27,000 US jobs in 2012.

“And we love it,” Keen says. “We all use Amazon. We strike this Faustian deal. It’s ultra-convenient, fantastic service, great interface, absurdly cheap prices. But what’s the cost? Truly appalling working conditions; we know this. Deep hostility to unions. A massive impact on independent retail; in books, savage bullying of publishers. This is back to the early years of the 19th century. But we’re seduced into thinking it’s good; Amazon has told us what we want to hear. Bezos says, ‘This is about you, the consumer.’ The problem is, we’re not just consumers. We’re citizens, too.”

Read the entire article here.

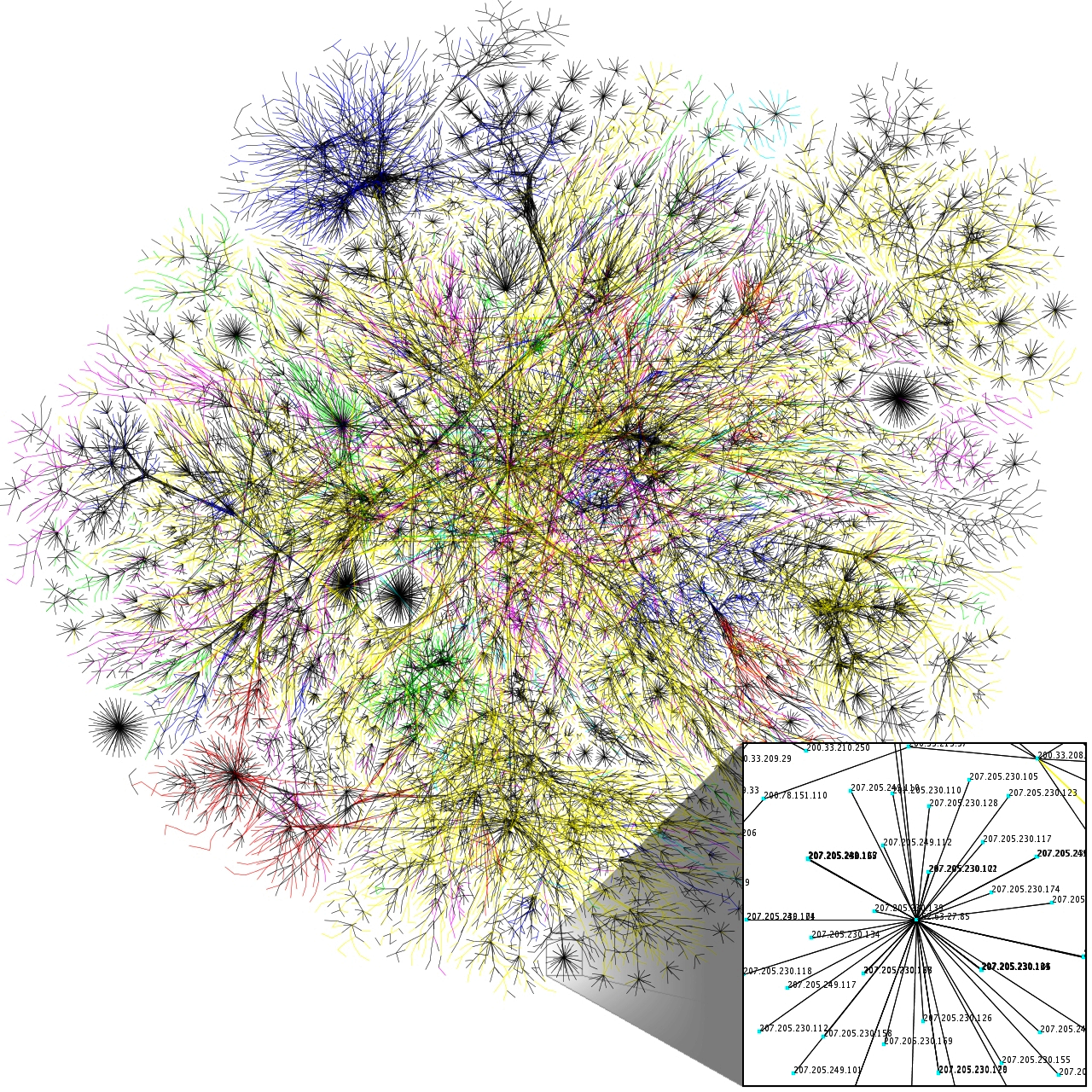

Image: Visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet. Courtesy of the Opte Project.

Technology is altering the lives of us all. Often it is a positive influence, offering its users tremendous benefits from time-saving to life-extension. However, the relationship of technology to our employment is more complex and usually detrimental.

Technology is altering the lives of us all. Often it is a positive influence, offering its users tremendous benefits from time-saving to life-extension. However, the relationship of technology to our employment is more complex and usually detrimental.