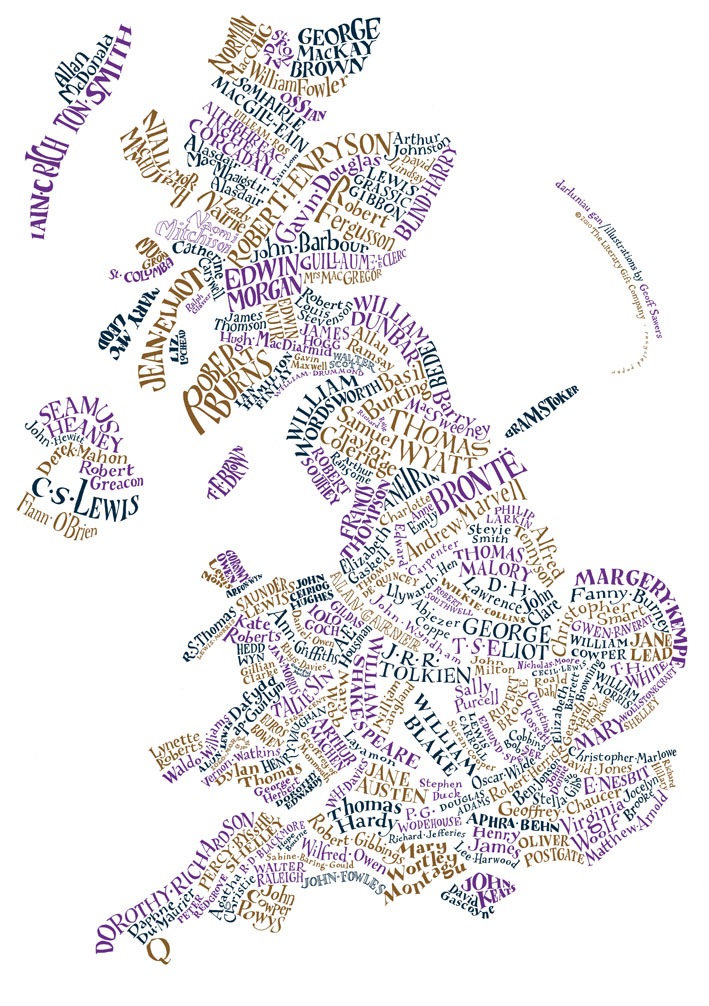

Frank Jacobs over at Strange Maps has found another really cool map. This one shows 181 British writers placed according to the part of the British Isles with which they are best associated.

Frank Jacobs over at Strange Maps has found another really cool map. This one shows 181 British writers placed according to the part of the British Isles with which they are best associated.

[div class=attrib]From Strange Maps:[end-div]

Maps usually display only one layer of information. In most cases, they’re limited to the topography, place names and traffic infrastructure of a certain region. True, this is very useful, and in all fairness quite often it’s all we ask for. But to reduce cartography to a schematic of accessibility is to exclude the poetry of place.

Or in this case, the poetry and prose of place. This literary map of Britain is composed of the names of 181 British writers, each positioned in parts of the country with which they are associated.

This is not the best navigational tool imaginable. If you want to go from William Wordsworth to Alfred Tennyson, you could pass through Coleridge and Thomas Wyatt, slice through the Brontë sisters, step over Andrew Marvell and finally traverse Philip Larkin. All of which sounds kind of messy.

t’s also rather limited. To reduce the whole literary history of Britain to nine score and one writers can only be done by the exclusion of many other, at least equally worthy contributors to the country’s literary landscape. But completeness is not the point of this map: it is not an instrument for literary-historical navigation either. Its main purpose is sheer cartographic joy.

An added bonus is that we’re able to geo-locate some of English literature’s best-known names. Seamus Heaney is about as Irish as a pint of Guinness for breakfast on March 17th, but it’s a bit of a surprise to see C.S. Lewis placed in Northern Ireland as well. The writer of the Narnia saga is closely associated with Oxford, but was indeed born and raised in Belfast.

Thomas Hardy’s name fills out an area close to Wessex, the fictional west country where much of his stories are set. London is occupied by Ben Jonson and John Donne, among others. Hanging around the capital are Geoffrey Chaucer, who was born there, and Christopher Marlowe, a native of Canterbury. The Isle of Wight is formed by the names of David Gascoyne, the surrealist poet, and John Keats, the romantic poet. Neither was born on the island, but both spent some time there.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]