In case you may not have heard, sugar is bad for you. In fact, an increasing number of food scientists will tell you that sugar is a poison, and that it’s time to fight the sugar oligarchs in much the same way that health advocates resolved to take on big tobacco many decades ago.

In case you may not have heard, sugar is bad for you. In fact, an increasing number of food scientists will tell you that sugar is a poison, and that it’s time to fight the sugar oligarchs in much the same way that health advocates resolved to take on big tobacco many decades ago.

From the Guardian:

If you have any interest at all in diet, obesity, public health, diabetes, epidemiology, your own health or that of other people, you will probably be aware that sugar, not fat, is now considered the devil’s food. Dr Robert Lustig’s book, Fat Chance: The Hidden Truth About Sugar, Obesity and Disease, for all that it sounds like a Dan Brown novel, is the difference between vaguely knowing something is probably true, and being told it as a fact. Lustig has spent the past 16 years treating childhood obesity. His meta-analysis of the cutting-edge research on large-cohort studies of what sugar does to populations across the world, alongside his own clinical observations, has him credited with starting the war on sugar. When it reaches the enemy status of tobacco, it will be because of Lustig.

“Politicians have to come in and reset the playing field, as they have with any substance that is toxic and abused, ubiquitous and with negative consequence for society,” he says. “Alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine. We don’t have to ban any of them. We don’t have to ban sugar. But the food industry cannot be given carte blanche. They’re allowed to make money, but they’re not allowed to make money by making people sick.”

Lustig argues that sugar creates an appetite for itself by a determinable hormonal mechanism – a cycle, he says, that you could no more break with willpower than you could stop feeling thirsty through sheer strength of character. He argues that the hormone related to stress, cortisol, is partly to blame. “When cortisol floods the bloodstream, it raises blood pressure; increases the blood glucose level, which can precipitate diabetes. Human research shows that cortisol specifically increases caloric intake of ‘comfort foods’.” High cortisol levels during sleep, for instance, interfere with restfulness, and increase the hunger hormone ghrelin the next day. This differs from person to person, but I was jolted by recognition of the outrageous deliciousness of doughnuts when I haven’t slept well.

“The problem in obesity is not excess weight,” Lustig says, in the central London hotel that he has made his anti-metabolic illness HQ. “The problem with obesity is that the brain is not seeing the excess weight.” The brain can’t see it because appetite is determined by a binary system. You’re either in anorexigenesis – “I’m not hungry and I can burn energy” – or you’re in orexigenesis – “I’m hungry and I want to store energy.” The flip switch is your leptin level (the hormone that regulates your body fat) but too much insulin in your system blocks the leptin signal.

It helps here if you have ever been pregnant or remember much of puberty and that savage hunger; the way it can trick you out of your best intentions, the lure of ridiculous foods: six-month-old Christmas cake, sweets from a bin. If you’re leptin resistant – that is, if your insulin is too high as a result of your sugar intake – you’ll feel like that all the time.

Telling people to simply lose weight, he tells me, “is physiologically impossible and it’s clinically dangerous. It’s a goal that’s not achievable.” He explains further in the book: “Biochemistry drives behaviour. You see a patient who drinks 10 gallons of water a day and urinates 10 gallons of water a day. What is wrong with him? Could he have a behavioural disorder and be a psychogenic water drinker? Could be. Much more likely he has diabetes.” To extend that, you could tell people with diabetes not to drink water, and 3% of them might succeed – the outliers. But that wouldn’t help the other 97% just as losing the weight doesn’t, long-term, solve the metabolic syndrome – the addiction to sugar – of which obesity is symptomatic.

Many studies have suggested that diets tend to work for two months, some for as long as six. “That’s what the data show. And then everybody’s weight comes roaring back.” During his own time working night shifts, Lustig gained 3st, which he never lost and now uses exuberantly to make two points. The first is that weight is extremely hard to lose, and the second – more important, I think – is that he’s no diet and fitness guru himself. He doesn’t want everybody to be perfect: he’s just a guy who doesn’t want to surrender civilisation to diseases caused by industry. “I’m not a fitness guru,” he says, puckishly. “I’m 45lb overweight!”

“Sugar causes diseases: unrelated to their calories and unrelated to the attendant weight gain. It’s an independent primary-risk factor. Now, there will be food-industry people who deny it until the day they die, because their livelihood depends on it.” And here we have the reason why he sees this is a crusade and not a diet book, the reason that Lustig is in London and not Washington. This is an industry problem; the obesity epidemic began in 1980. Back then, nobody knew about leptin. And nobody knew about insulin resistance until 1984.

“What they knew was, when they took the fat out they had to put the sugar in, and when they did that, people bought more. And when they added more, people bought more, and so they kept on doing it. And that’s how we got up to current levels of consumption.” Approximately 80% of the 600,000 packaged foods you can buy in the US have added calorific sweeteners (this includes bread, burgers, things you wouldn’t add sugar to if you were making them from scratch). Daily fructose consumption has doubled in the past 30 years in the US, a pattern also observable (though not identical) here, in Canada, Malaysia, India, right across the developed and developing world. World sugar consumption has tripled in the past 50 years, while the population has only doubled; it makes sense of the obesity pandemic.

“It would have happened decades earlier; the reason it didn’t was that sugar wasn’t cheap. The thing that made it cheap was high-fructose corn syrup. They didn’t necessarily know the physiology of it, but they knew the economics of it.” Adding sugar to everyday food has become as much about the industry prolonging the shelf life as it has about palatability; if you’re shopping from corner shops, you’re likely to be eating unnecessary sugar in pretty well everything. It is difficult to remain healthy in these conditions. “You here in Britain are light years ahead of us in terms of understanding the problem. We don’t get it in the US, we have this libertarian streak. You don’t have that. You’re going to solve it first. So it’s in my best interests to help you, because that will help me solve it back there.”

The problem has mushroomed all over the world in 30 years and is driven by the profits of the food and diet industries combined. We’re not looking at a global pandemic of individual greed and fecklessness: it would be impossible for the citizens of the world to coordinate their human weaknesses with that level of accuracy. Once you stop seeing it as a problem of personal responsibility it’s easier to accept how profound and serious the war on sugar is. Life doesn’t have to become wholemeal and joyless, but traffic-light systems and five-a-day messaging are under-ambitious.

“The problem isn’t a knowledge deficit,” an obesity counsellor once told me. “There isn’t a fat person on Earth who doesn’t know vegetables are good for you.” Lustig agrees. “I, personally, don’t have a lot of hope that those things will turn things around. Education has not solved any substance of abuse. This is a substance of abuse. So you need two things, you need personal intervention and you need societal intervention. Rehab and laws, rehab and laws. Education would come in with rehab. But we need laws.”

Read the entire article here.

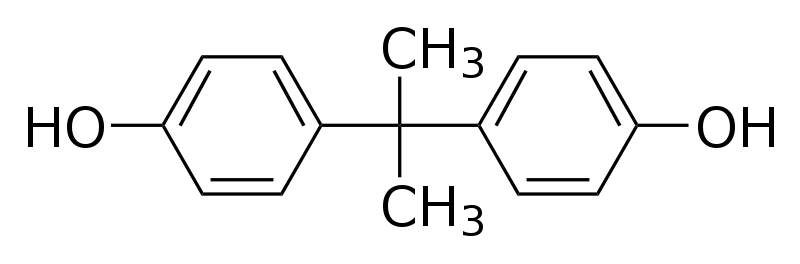

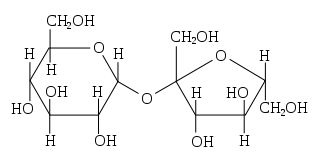

Image: Molecular diagrams of sucrose (left) and fructose (right). Courtesy of Wikipedia.