Every couple of years a (hell)fire and brimstone preacher floats into the national consciousness and makes the headlines with certain predictions from the book regarding imminent destruction of our species and home. Most recently Harold Camping, the radio evangelist, predicted the apocalypse would begin on Saturday, May 21, 2011. His subsequent revision placed the “correct date” at October 21, 2011. Well, we’re still here, so the next apocalyptic date to prepare for, according to watchers of all things Mayan, is December 21, 2012.

So not to be outdone by prophesy from one particular religion or another, science has come out swinging with its own list of potential apocalyptic end-of-days. No surprise, many scenarios may well be at our own hands.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

Stories of brimstone, fire and gods make good tales and do a decent job of stirring up the requisite fear and jeopardy. But made-up doomsday tales pale into nothing, creatively speaking, when contrasted with what is actually possible. Look through the lens of science and “the end” becomes much more interesting.

Since the beginning of life on Earth, around 3.5 billion years ago, the fragile existence has lived in the shadow of annihilation. On this planet, extinction is the norm – of the 4 billion species ever thought to have evolved, 99% have become extinct. In particular, five times in this past 500 million years the steady background rate of extinction has shot up for a period of time. Something – no one knows for sure what – turned the Earth into exactly the wrong planet for life at these points and during each mass extinction, more than 75% of the existing species died off in a period of time that was, geologically speaking, a blink of the eye.

One or more of these mass extinctions occurred because of what we could call the big, Hollywood-style, potential doomsday scenarios. If a big enough asteroid hit the Earth, for example, the impact would cause huge earthquakes and tsunamis that could cross the globe. There would be enough dust thrown into the air to block out the sun for several years. As a result, the world’s food resources would be destroyed, leading to famine. It has happened before: the dinosaurs (along with more than half the other species on Earth) were wiped out 65 million years ago by a 10km-wide asteroid that smashed into the area around Mexico.

…

Other natural disasters include sudden changes in climate or immense volcanic eruptions. All of these could cause global catastrophes that would wipe out large portions of the planet’s life, but, given we have survived for several hundreds of thousands of years while at risk of these, it is unlikely that a natural disaster such as that will cause catastrophe in the next few centuries.

In addition, cosmic threats to our existence have always been with us, even thought it has taken us some time to notice: the collision of our galaxy, the Milky Way, with our nearest neighbour, Andromeda, for example, or the arrival of a black hole. Common to all of these threats is that there is very little we can do about them even when we know the danger exists, except trying to work out how to survive the aftermath.

But in reality, the most serious risks for humans might come from our own activities. Our species has the unique ability in the history of life on Earth to be the first capable of remaking our world. But we can also destroy it.

…

All too real are the human-caused threats born of climate change, excess pollution, depletion of natural resources and the madness of nuclear weapons. We tinker with our genes and atoms at our own peril. Nanotechnology, synthetic biology and genetic modification offer much potential in giving us better food to eat, safer drugs and a cleaner world, but they could also go wrong if misapplied or if we charge on without due care.

…

Some strange ways to go and their corresponding danger signs listed below:

DEATH BY EUPHORIA

Many of us use drugs such as caffeine or nicotine every day. Our increased understanding of physiology brings new drugs that can lift mood, improve alertness or keep you awake for days. How long before we use so many drugs we are no longer in control? Perhaps the end of society will not come with a bang, but fade away in a haze.

Danger sign: Drugs would get too cheap to meter, but you might be too doped up to notice.

VACUUM DECAY

If the Earth exists in a region of space known as a false vacuum, it could collapse into a lower-energy state at any point. This collapse would grow at the speed of light and our atoms would not hold together in the ensuing wave of intense energy – everything would be torn apart.

Danger sign: There would be no signs. It could happen half way through this…

STRANGELETS

Quantum mechanics contains lots of frightening possibilities. Among them is a particle called a strangelet that can transform any other particle into a copy of itself. In just a few hours, a small chunk of these could turn a planet into a featureless mass of strangelets. Everything that planet was would be no more.

Danger sign: Everything around you starts cooking, releasing heat.

END OF TIME

What if time itself somehow came to a finish because of the laws of physics? In 2007, Spanish scientists proposed an alternative explanation for the mysterious dark energy that accounts for 75% of the mass of the universe and acts as a sort of anti-gravity, pushing galaxies apart. They proposed that the effects we observe are due to time slowing down as it leaked away from our universe.

Danger sign: It could be happening right now. We would never know.

MEGA TSUNAMI

Geologists worry that a future volcanic eruption at La Palma in the Canary Islands might dislodge a chunk of rock twice the volume of the Isle of Man into the Atlantic Ocean, triggering waves a kilometre high that would move at the speed of a jumbo jet with catastrophic effects for the shores of the US, Europe, South America and Africa.

Danger sign: Half the world’s major cities are under water. All at once.

GEOMAGNETIC REVERSAL

The Earth’s magnetic field provides a shield against harmful radiation from our sun that could rip through DNA and overload the world’s electrical systems. Every so often, Earth’s north and south poles switch positions and, during the transition, the magnetic field will weaken or disappear for many years. The last known transition happened almost 780,000 years ago and it is likely to happen again.

Danger sign: Electronics stop working.

GAMMA RAYS FROM SPACE

When a supermassive star is in its dying moments, it shoots out two beams of high-energy gamma rays into space. If these were to hit Earth, the immense energy would tear apart the atmosphere’s air molecules and disintegrate the protective ozone layer.

Danger sign: The sky turns brown and all life on the surface slowly dies.

RUNAWAY BLACK HOLE

Black holes are the most powerful gravitational objects in the universe, capable of tearing Earth into its constituent atoms. Even within a billion miles, a black hole could knock Earth out of the solar system, leaving our planet wandering through deep space without a source of energy.

Danger sign: Increased asteroid activity; the seasons get really extreme.

INVASIVE SPECIES

Invasive species are plants, animals or microbes that turn up in an ecosystem that has no protection against them. The invader’s population surges and the ecosystem quickly destabilises towards collapse. Invasive species are already an expensive global problem: they disrupt local ecosystems, transfer viruses, poison soils and damage agriculture.

Danger sign: Your local species disappear.

TRANSHUMANISM

What if biological and technological enhancements took humans to a level where they radically surpassed anything we know today? “Posthumans” might consist of artificial intelligences based on the thoughts and memories of ancient humans, who uploaded themselves into a computer and exist only as digital information on superfast computer networks. Their physical bodies might be gone but they could access and store endless information and share their thoughts and feelings immediately and unambiguously with other digital humans.

Danger sign: You are outcompeted, mentally and physically, by a cyborg.

[div class=attrib]Read more of this article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]End is Nigh Sign. Courtesy of frontporchrepublic.com.[end-div]

Pseudoscience can be fun — for comedic purposes only of course. But when it is taken seriously and dogmatically, as it often is by a significant number of people, it imperils rational dialogue and threatens real scientific and cultural progress. There is no end to the lengthy list of fake scientific claims and theories — some of our favorites include: the moon “landing” conspiracy, hollow Earth, Bermuda triangle, crop circles, psychic surgery, body earthing, room temperature fusion, perpetual and motion machines.

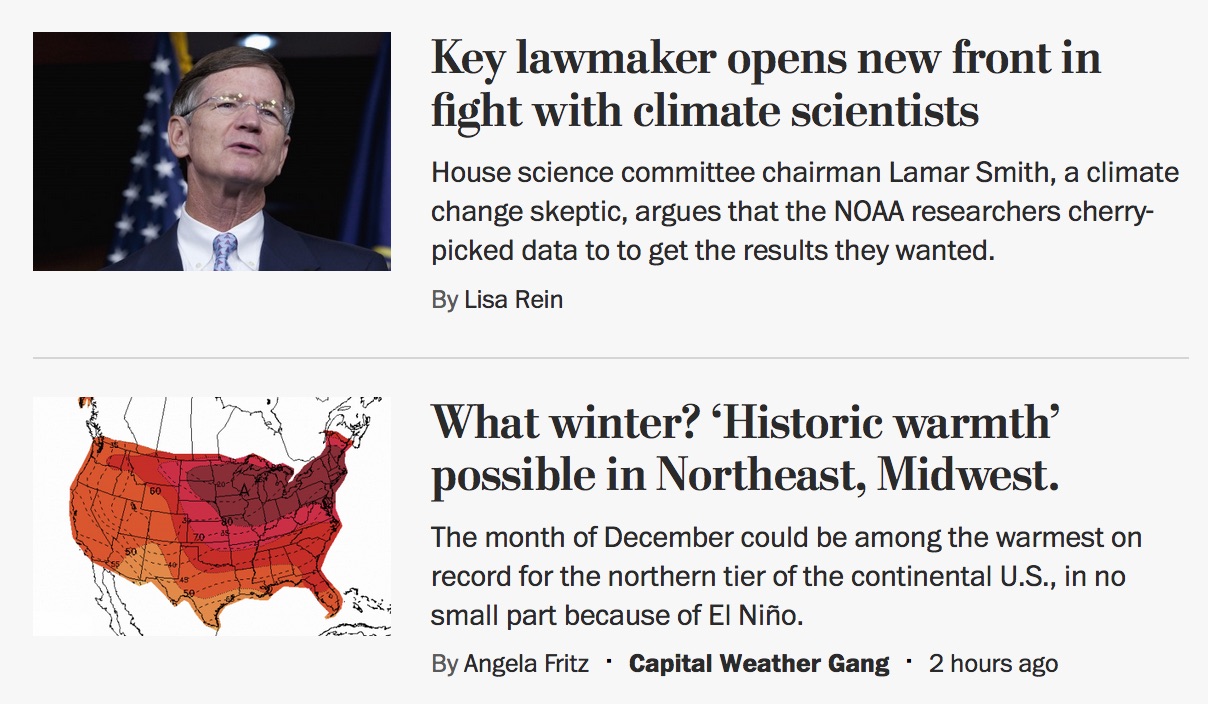

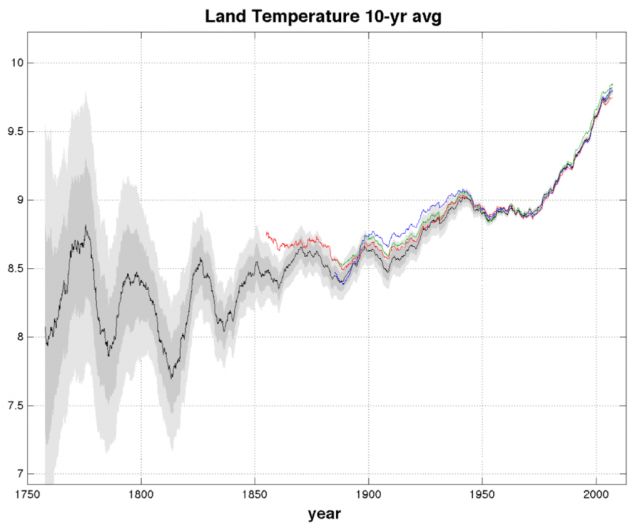

Pseudoscience can be fun — for comedic purposes only of course. But when it is taken seriously and dogmatically, as it often is by a significant number of people, it imperils rational dialogue and threatens real scientific and cultural progress. There is no end to the lengthy list of fake scientific claims and theories — some of our favorites include: the moon “landing” conspiracy, hollow Earth, Bermuda triangle, crop circles, psychic surgery, body earthing, room temperature fusion, perpetual and motion machines. Some believe that AIDS was created by the U.S. Government or bestowed by a malevolent god. Some believe that Neil Armstrong never set foot on the moon, while others believe that Nazis first established a moon base in 1942. Some believe that recent tsunamis were caused by the U.S. military, and that said military is hiding evidence of alien visits in Area 51, Nevada. The latest of course is the great conspiracy of climate change, which apparently is created by socialists seeking to destroy the United States. This conspiratorial thinking makes for good reality-TV, and presents wonderful opportunities for psychological research. Why after all, in the face of seemingly insurmountable evidence, widespread common consensus and fundamental scientific reasoning, do such ideas, and their believers persist?

Some believe that AIDS was created by the U.S. Government or bestowed by a malevolent god. Some believe that Neil Armstrong never set foot on the moon, while others believe that Nazis first established a moon base in 1942. Some believe that recent tsunamis were caused by the U.S. military, and that said military is hiding evidence of alien visits in Area 51, Nevada. The latest of course is the great conspiracy of climate change, which apparently is created by socialists seeking to destroy the United States. This conspiratorial thinking makes for good reality-TV, and presents wonderful opportunities for psychological research. Why after all, in the face of seemingly insurmountable evidence, widespread common consensus and fundamental scientific reasoning, do such ideas, and their believers persist? Why study the science of climate change when you can study the complexities of climate change deniers themselves? That was the question that led several groups of independent researchers to study why some groups of people cling to mistaken beliefs and hold inaccurate views of the public consensus.

Why study the science of climate change when you can study the complexities of climate change deniers themselves? That was the question that led several groups of independent researchers to study why some groups of people cling to mistaken beliefs and hold inaccurate views of the public consensus.

Skeptic

Skeptic