Ray Bradbury’s death on June 5 reminds us of his uncanny gift for inventing a future that is much like our modern day reality.

Bradbury’s body of work beginning in the early 1940s introduced us to ATMs, wall mounted flat screen TVs, ear-piece radios, online social networks, self-driving cars, and electronic surveillance. Bravely and presciently he also warned us of technologically induced cultural amnesia, social isolation, indifference to violence, and dumbed-down 24/7 mass media.

An especially thoughtful opinion from author Tim Kreider on Bradbury’s life as a “misanthropic humanist”.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

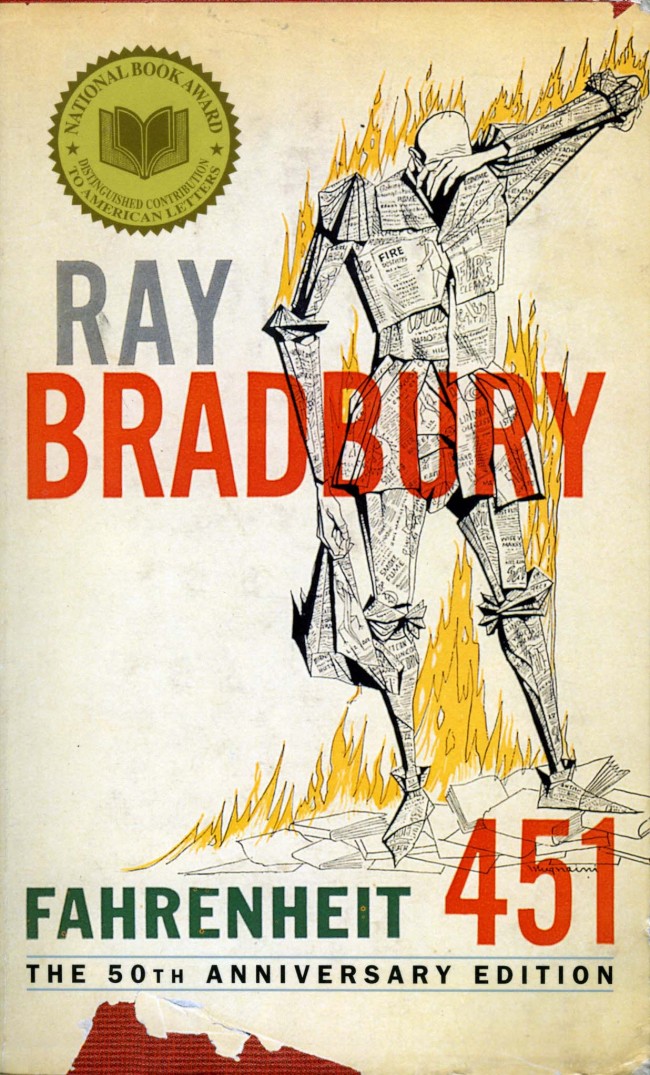

IF you’d wanted to know which way the world was headed in the mid-20th century, you wouldn’t have found much indication in any of the day’s literary prizewinners. You’d have been better advised to consult a book from a marginal genre with a cover illustration of a stricken figure made of newsprint catching fire.

Prescience is not the measure of a science-fiction author’s success — we don’t value the work of H. G. Wells because he foresaw the atomic bomb or Arthur C. Clarke for inventing the communications satellite — but it is worth pausing, on the occasion of Ray Bradbury’s death, to notice how uncannily accurate was his vision of the numb, cruel future we now inhabit.

Mr. Bradbury’s most famous novel, “Fahrenheit 451,” features wall-size television screens that are the centerpieces of “parlors” where people spend their evenings watching interactive soaps and vicious slapstick, live police chases and true-crime dramatizations that invite viewers to help catch the criminals. People wear “seashell” transistor radios that fit into their ears. Note the perversion of quaint terms like “parlor” and “seashell,” harking back to bygone days and vanished places, where people might visit with their neighbors or listen for the sound of the sea in a chambered nautilus.

Mr. Bradbury didn’t just extrapolate the evolution of gadgetry; he foresaw how it would stunt and deform our psyches. “It’s easy to say the wrong thing on telephones; the telephone changes your meaning on you,” says the protagonist of the prophetic short story “The Murderer.” “First thing you know, you’ve made an enemy.”

Anyone who’s had his intended tone flattened out or irony deleted by e-mail and had to explain himself knows what he means. The character complains that he’s relentlessly pestered with calls from friends and employers, salesmen and pollsters, people calling simply because they can. Mr. Bradbury’s vision of “tired commuters with their wrist radios, talking to their wives, saying, ‘Now I’m at Forty-third, now I’m at Forty-fourth, here I am at Forty-ninth, now turning at Sixty-first” has gone from science-fiction satire to dreary realism.

“It was all so enchanting at first,” muses our protagonist. “They were almost toys, to be played with, but the people got too involved, went too far, and got wrapped up in a pattern of social behavior and couldn’t get out, couldn’t admit they were in, even.”

Most of all, Mr. Bradbury knew how the future would feel: louder, faster, stupider, meaner, increasingly inane and violent. Collective cultural amnesia, anhedonia, isolation. The hysterical censoriousness of political correctness. Teenagers killing one another for kicks. Grown-ups reading comic books. A postliterate populace. “I remember the newspapers dying like huge moths,” says the fire captain in “Fahrenheit,” written in 1953. “No one wanted them back. No one missed them.” Civilization drowned out and obliterated by electronic chatter. The book’s protagonist, Guy Montag, secretly trying to memorize the Book of Ecclesiastes on a train, finally leaps up screaming, maddened by an incessant jingle for “Denham’s Dentrifice.” A man is arrested for walking on a residential street. Everyone locked indoors at night, immersed in the social lives of imaginary friends and families on TV, while the government bombs someone on the other side of the planet. Does any of this sound familiar?

The hero of “The Murderer” finally goes on a rampage and smashes all the yammering, blatting devices around him, expressing remorse only over the Insinkerator — “a practical device indeed,” he mourns, “which never said a word.” It’s often been remarked that for a science-fiction writer, Mr. Bradbury was something of a Luddite — anti-technology, anti-modern, even anti-intellectual. (“Put me in a room with a pad and a pencil and set me up against a hundred people with a hundred computers,” he challenged a Wired magazine interviewer, and swore he would “outcreate” every one.)

But it was more complicated than that; his objections were not so much reactionary or political as they were aesthetic. He hated ugliness, noise and vulgarity. He opposed the kind of technology that deadened imagination, the modernity that would trash the past, the kind of intellectualism that tried to centrifuge out awe and beauty. He famously did not care to drive or fly, but he was a passionate proponent of space travel, not because of its practical benefits but because he saw it as the great spiritual endeavor of the age, our generation’s cathedral building, a bid for immortality among the stars.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Technorati.[end-div]

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].