One has to wonder how Jean-Paul Sartre would have been regarded today had he accepted the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, or had the characters of Monty Python not used him as a punching bag in one of their infamous, satyrical philosopher sketches:

…

Mrs Conclusion: What was Jean-Paul like?

Mrs Premise: Well, you know, a bit moody. Yes, he didn’t join in the fun much. Just sat there thinking. Still, Mr Rotter caught him a few times with the whoopee cushion. (she demonstrates) Le Capitalisme et La Bourgeoisie ils sont la m~me chose… Oooh we did laugh…

From the Guardian:

In this age in which all shall have prizes, in which every winning author knows what’s necessary in the post-award trial-by-photoshoot (Book jacket pressed to chest? Check. Wall-to-wall media? Check. Backdrop of sponsor’s logo? Check) and in which scarcely anyone has the couilles, as they say in France, to politely tell judges where they can put their prize, how lovely to recall what happened on 22 October 1964, when Jean-Paul Sartre turned down the Nobel prize for literature.

“I have always declined official honours,” he explained at the time. “A writer should not allow himself to be turned into an institution. This attitude is based on my conception of the writer’s enterprise. A writer who adopts political, social or literary positions must act only within the means that are his own – that is, the written word.”

Throughout his life, Sartre agonised about the purpose of literature. In 1947’s What is Literature?, he jettisoned a sacred notion of literature as capable of replacing outmoded religious beliefs in favour of the view that it should have a committed social function. However, the last pages of his enduringly brilliant memoir Words, published the same year as the Nobel refusal, despair over that function: “For a long time I looked on my pen as a sword; now I know how powerless we are.” Poetry, wrote Auden, makes nothing happen; politically committed literature, Sartre was saying, was no better. In rejecting the honour, Sartre worried that the Nobel was reserved for “the writers of the west or the rebels of the east”. He didn’t damn the Nobel in quite the bracing terms that led Hari Kunzru to decline the 2003 John Llewellyn Rhys prize, sponsored by the Mail on Sunday (“As the child of an immigrant, I am only too aware of the poisonous effect of the Mail’s editorial line”), but gently pointed out its Eurocentric shortcomings. Plus, one might say 50 years on, ça change. Sartre said that he might have accepted the Nobel if it had been offered to him during France’s imperial war in Algeria, which he vehemently opposed, because then the award would have helped in the struggle, rather than making Sartre into a brand, an institution, a depoliticised commodity. Truly, it’s difficult not to respect his compunctions.

But the story is odder than that. Sartre read in Figaro Littéraire that he was in the frame for the award, so he wrote to the Swedish Academy saying he didn’t want the honour. He was offered it anyway. “I was not aware at the time that the Nobel prize is awarded without consulting the opinion of the recipient,” he said. “But I now understand that when the Swedish Academy has made a decision, it cannot subsequently revoke it.”

Regrets? Sartre had a few – at least about the money. His principled stand cost him 250,000 kronor (about £21,000), prize money that, he reflected in his refusal statement, he could have donated to the “apartheid committee in London” who badly needed support at the time. All of which makes one wonder what his compatriot, Patrick Modiano, the 15th Frenchman to win the Nobel for literature earlier this month, did with his 8m kronor (about £700,000).

The Swedish Academy had selected Sartre for having “exerted a far-reaching influence on our age”. Is this still the case? Though he was lionised by student radicals in Paris in May 1968, his reputation as a philosopher was on the wane even then. His brand of existentialism had been eclipsed by structuralists (such as Lévi-Strauss and Althusser) and post-structuralists (such as Derrida and Deleuze). Indeed, Derrida would spend a great deal of effort deriding Sartrean existentialism as a misconstrual of Heidegger. Anglo-Saxon analytic philosophy, with the notable exception of Iris Murdoch and Arthur Danto, has for the most part been sniffy about Sartre’s philosophical credentials.

Sartre’s later reputation probably hasn’t benefited from being championed by Paris’s philosophical lightweight, Bernard-Henri Lévy, who subtitled his biography of his hero The Philosopher of the Twentieth Century (Really? Not Heidegger, Russell, Wittgenstein or Adorno?); still less by his appearance in Monty Python’s least funny philosophy sketch, “Mrs Premise and Mrs Conclusion visit Jean-Paul Sartre at his Paris home”. Sartre has become more risible than lisible: unremittingly depicted as laughable philosopher toad – ugly, randy, incomprehensible, forever excitably over-caffeinated at Les Deux Magots with Simone de Beauvoir, encircled with pipe smoke and mired in philosophical jargon, not so much a man as a stock pantomime figure. He deserves better.

How then should we approach Sartre’s writings in 2014? So much of his lifelong intellectual struggle and his work still seems pertinent. When we read the “Bad Faith” section of Being and Nothingness, it is hard not to be struck by the image of the waiter who is too ingratiating and mannered in his gestures, and how that image pertains to the dismal drama of inauthentic self-performance that we find in our culture today. When we watch his play Huis Clos, we might well think of how disastrous our relations with other people are, since we now require them, more than anything else, to confirm our self-images, while they, no less vexingly, chiefly need us to confirm theirs. When we read his claim that humans can, through imagination and action, change our destiny, we feel something of the burden of responsibility of choice that makes us moral beings. True, when we read such sentences as “the being by which Nothingness comes to the world must be its own Nothingness”, we might want to retreat to a dark room for a good cry, but let’s not spoil the story.

His lifelong commitments to socialism, anti-fascism and anti-imperialism still resonate. When we read, in his novel Nausea, of the protagonost Antoine Roquentin in Bouville’s art gallery, looking at pictures of self-satisfied local worthies, we can apply his fury at their subjects’ self-entitlement to today’s images of the powers that be (the suppressed photo, for example, of Cameron and his cronies in Bullingdon pomp), and share his disgust that such men know nothing of what the world is really like in all its absurd contingency.

In his short story Intimacy, we confront a character who, like all of us on occasion, is afraid of the burden of freedom and does everything possible to make others take her decisions for her. When we read his distinctions between being-in-itself (être-en-soi), being-for-itself (être-pour-soi) and being-for-others (être-pour-autrui), we are encouraged to think about the tragicomic nature of what it is to be human – a longing for full control over one’s destiny and for absolute identity, and at the same time, a realisation of the futility of that wish.

The existential plight of humanity, our absurd lot, our moral and political responsibilities that Sartre so brilliantly identified have not gone away; rather, we have chosen the easy path of ignoring them. That is not a surprise: for Sartre, such refusal to accept what it is to be human was overwhelmingly, paradoxically, what humans do.

Read the entire article here.

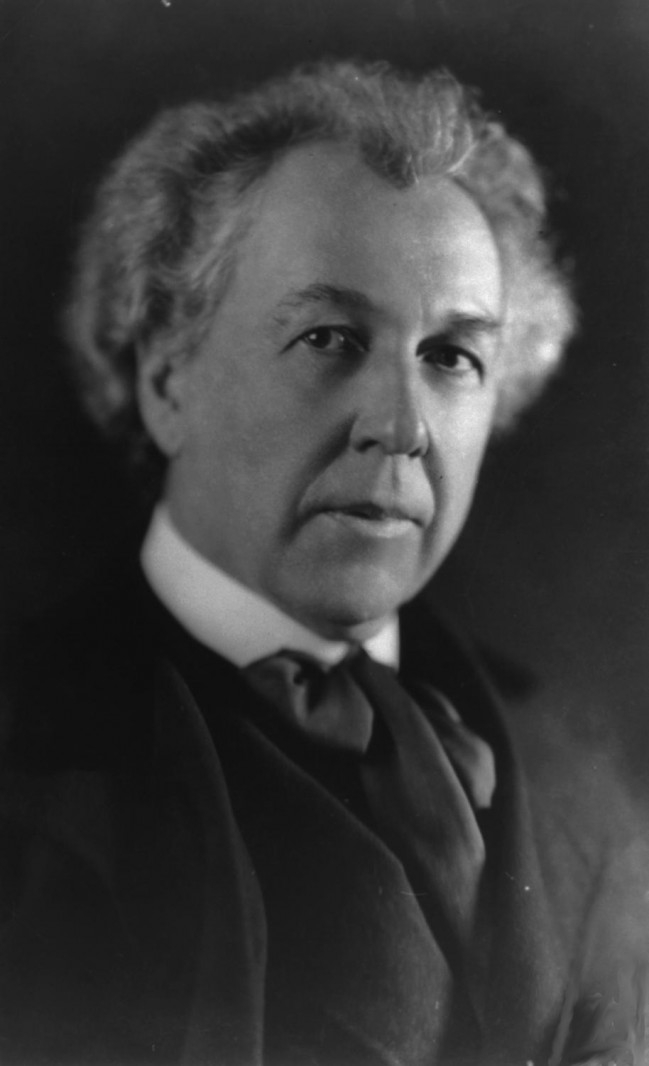

Image: Jean-Paul Sartre (c1950). Courtesy: Archivo del diario Clarín, Buenos Aires, Argentina