Yes, it’s official. There really is a subset of the Queen’s English for the contemporary art scene — dubbed International Art English (IAE). If you’ve visited a gallery over the last couple of decades you may be familiar with this type language on press releases and wall tags. It uses multisyllabic words in breathless, flowery, billowy sentences; high-brow phraseology replete with pretentious insider nods and winks; it’s often enthusiastically festooned with adverbs and esoteric adjectives, in apparently random but clear juxtaposition. So, it’s rather like the preceding sentence. Will IAE become as pervasive as International Sport English – you know, that subset of language increasingly spoken, in the same accent, by international sports celebrities? Time will tell.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

The Simon Lee Gallery in Mayfair is currently showing work by the veteran American artist Sherrie Levine. A dozen small pink skulls in glass cases face the door. A dozen small bronze mirrors, blandly framed but precisely arranged, wink from the walls. In the deep, quiet space of the London gallery, shut away from Mayfair’s millionaire traffic jams, all is minimal, tasteful and oddly calming.

Until you read the exhibition hand-out. “The artist brings the viewer face to face with their own preconceived hierarchy of cultural values and assumptions of artistic worth,” it says. “Each mirror imaginatively propels its viewer forward into the seemingly infinite progression of possible reproductions that the artist’s practice engenders, whilst simultaneously pulling them backwards in a quest for the ‘original’ source or referent that underlines Levine’s oeuvre.”

If you’ve been to see contemporary art in the last three decades, you will probably be familiar with the feelings of bafflement, exhaustion or irritation that such gallery prose provokes. You may well have got used to ignoring it. As Polly Staple, art writer and director of the Chisenhale Gallery in London, puts it: “There are so many people who come to our shows who don’t even look at the programme sheet. They don’t want to look at any writing about art.”

With its pompous paradoxes and its plagues of adverbs, its endless sentences and its strained rebellious poses, much of this promotional writing serves mainly, it seems, as ammunition for those who still insist contemporary art is a fraud. Surely no one sensible takes this jargon seriously?

David Levine and Alix Rule do. “Art English is something that everyone in the art world bitches about all the time,” says Levine, a 42-year-old American artist based in New York and Berlin. “But we all use it.” Three years ago, Levine and his friend Rule, a 29-year-old critic and sociology PhD student at Columbia university in New York, decided to try to anatomise it. “We wanted to map it out,” says Levine, “to describe its contours, rather than just complain about it.”

They christened it International Art English, or IAE, and concluded that its purest form was the gallery press release, which – in today’s increasingly globalised, internet-widened art world – has a greater audience than ever. “We spent hours just printing them out and reading them to each other,” says Levine. “We’d find some super-outrageous sentence and crack up about it. Then we’d try to understand the reality conveyed by that sentence.”

Next, they collated thousands of exhibition announcements published since 1999 by e-flux, a powerful New York-based subscriber network for art-world professionals. Then they used some language-analysing software called Sketch Engine, developed by a company in Brighton, to discover what, if anything, lay behind IAE’s great clouds of verbiage.

Their findings were published last year as an essay in the voguish American art journal Triple Canopy; it has since become one of the most widely and excitedly circulated pieces of online cultural criticism. It is easy to see why. Levine and Rule write about IAE in a droll, largely jargon-free style. They call it “a unique language” that has “everything to do with English, but is emphatically not English. [It] is oddly pornographic: we know it when we see it.”

IAE always uses “more rather than fewer words”. Sometimes it uses them with absurd looseness: “Ordinary words take on non-specific alien functions. ‘Reality,’ writes artist Tania Bruguera, ‘functions as my field of action.'” And sometimes it deploys words with faddish precision: “Usage of the word speculative spiked unaccountably in 2009; 2011 saw a sudden rage for rupture; transversal now seems poised to have its best year ever.”

Through Sketch Engine, Rule and Levine found that “the real” – used as a portentous, would-be philosophical abstract noun – occurred “179 times more often” in IAE than in standard English. In fact, in its declarative, multi-clause sentences, and in its odd combination of stiffness and swagger, they argued that IAE “sounds like inexpertly translated French”. This was no coincidence, they claimed, having traced the origins of IAE back to French post-structuralism and the introduction of its slippery ideas and prose style into American art writing via October, the New York critical journal founded in 1976. Since then, IAE had spread across the world so thoroughly that there was even, wrote Rule and Levine, an “IAE of the French press release … written, we can only imagine, by French interns imitating American interns imitating American academics imitating French academics”.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article following the jump.[end-div]

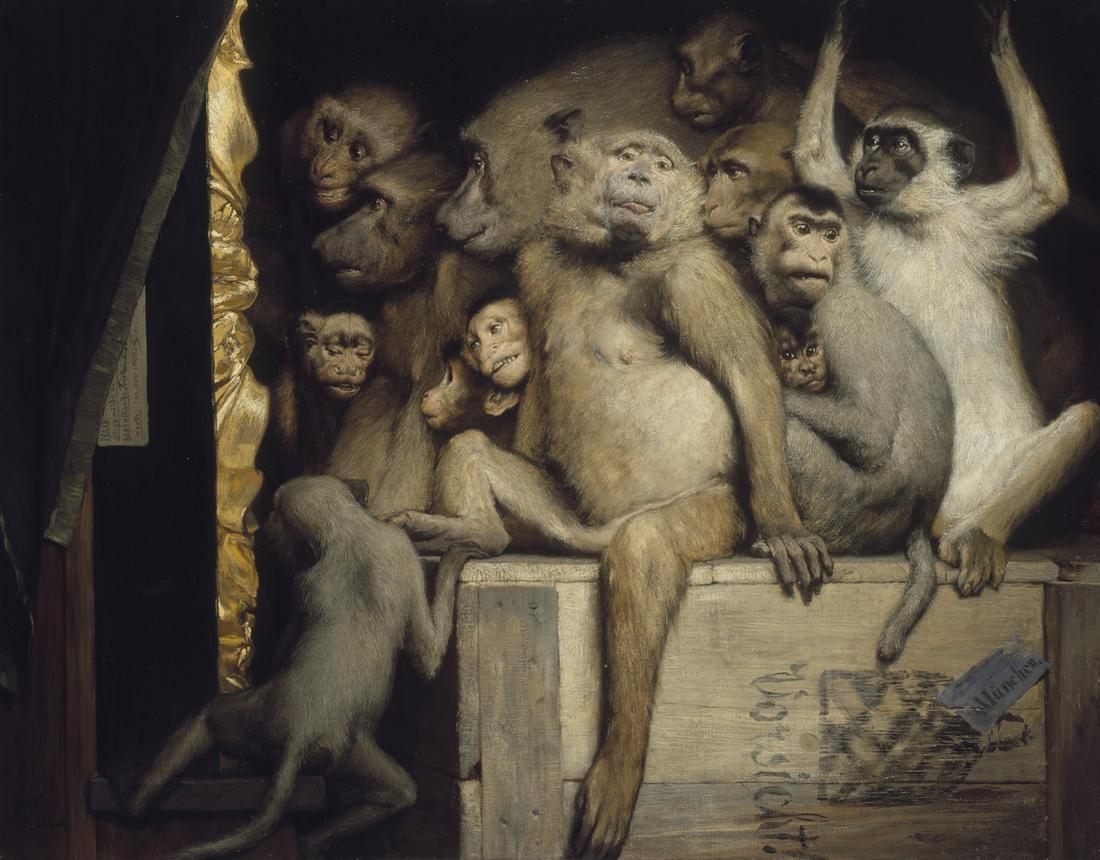

[div class=attrib]Image: Monkeys as Judges of Art, 1889, by Gabriel Cornelius von Max. Courtesy of Wikipedia / Public Domain.[end-div]

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

Accessorize

Accessorize

Slip

Slip

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

Once in a while a photographer comes along with a simple yet thoroughly new perspective. Japanese artist Photographer Hal fits this description. His images of young Japanese in a variety of contorted and enclosed situations are sometimes funny and disturbing, but certainly different and provocative.

Once in a while a photographer comes along with a simple yet thoroughly new perspective. Japanese artist Photographer Hal fits this description. His images of young Japanese in a variety of contorted and enclosed situations are sometimes funny and disturbing, but certainly different and provocative. Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?