[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

TACKLING a crossword can crowd the tip of your tongue. You know that you know the answers to 3 down and 5 across, but the words just won’t come out. Then, when you’ve given up and moved on to another clue, comes blessed relief. The elusive answer suddenly occurs to you, crystal clear.

The processes leading to that flash of insight can illuminate many of the human mind’s curious characteristics. Crosswords can reflect the nature of intuition, hint at the way we retrieve words from our memory, and reveal a surprising connection between puzzle solving and our ability to recognise a human face.

“What’s fascinating about a crossword is that it involves many aspects of cognition that we normally study piecemeal, such as memory search and problem solving, all rolled into one ball,” says Raymond Nickerson, a psychologist at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. In a paper published earlier this year, he brought profession and hobby together by analysing the mental processes of crossword solving (Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, vol 18, p 217).

1 across: “You stinker!” – audible cry that allegedly marked displacement activity (6)

Most of our mental machinations take place pre-consciously, with the results dropping into our conscious minds only after they have been decided elsewhere in the brain. Intuition plays a big role in solving a crossword, Nickerson observes. Indeed, sometimes your pre-conscious mind may be so quick that it produces the goods instantly.

At other times, you might need to take a more methodical approach and consider possible solutions one by one, perhaps listing synonyms of a word in the clue.

Even if your list doesn’t seem to make much sense, it might reflect the way your pre-conscious mind is homing in on the solution. Nickerson points to work in the 1990s by Peter Farvolden at the University of Toronto in Canada, who gave his subjects four-letter fragments of seven-letter target words (as may happen in some crossword layouts, especially in the US, where many words overlap). While his volunteers attempted to work out the target, they were asked to give any other word that occurred to them in the meantime. The words tended to be associated in meaning with the eventual answer, hinting that the pre-conscious mind solves a problem in steps.

Should your powers of deduction fail you, it may help to let your mind chew over the clue while your conscious attention is elsewhere. Studies back up our everyday experience that a period of incubation can lead you to the eventual “aha” moment. Don’t switch off entirely, though. For verbal problems, a break from the clue seems to be more fruitful if you occupy yourself with another task, such as drawing a picture or reading (Psychological Bulletin, vol 135, p 94).

So if 1 across has you flummoxed, you could leave it and take a nice bath, or better still read a novel. Or just move on to the next clue.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Newspaper crossword puzzle. Courtesy of Polytechnic West.[end-div]

The social standing of atheists seems to be on the rise. Back in December we

The social standing of atheists seems to be on the rise. Back in December we  Seventeenth century polymath Blaise Pascal had it right when he remarked, “Distraction is the only thing that consoles us for our miseries, and yet it is itself the greatest of our miseries.”

Seventeenth century polymath Blaise Pascal had it right when he remarked, “Distraction is the only thing that consoles us for our miseries, and yet it is itself the greatest of our miseries.” Let’s face it, taking money out of politics in the United States, especially since the 2010 Supreme Court Decision (

Let’s face it, taking money out of politics in the United States, especially since the 2010 Supreme Court Decision (

Over the last 40 years or so physicists and cosmologists have sought to construct a single grand theory that describes our entire universe from the subatomic soup that makes up particles and describes all forces to the vast constructs of our galaxies, and all in between and beyond. Yet a major stumbling block has been how to bring together the quantum theories that have so successfully described, and predicted, the microscopic with our current understanding of gravity. String theory is one such attempt to develop a unified theory of everything, but it remains jumbled with many possible solutions and, currently, is beyond experimental verification.

Over the last 40 years or so physicists and cosmologists have sought to construct a single grand theory that describes our entire universe from the subatomic soup that makes up particles and describes all forces to the vast constructs of our galaxies, and all in between and beyond. Yet a major stumbling block has been how to bring together the quantum theories that have so successfully described, and predicted, the microscopic with our current understanding of gravity. String theory is one such attempt to develop a unified theory of everything, but it remains jumbled with many possible solutions and, currently, is beyond experimental verification.

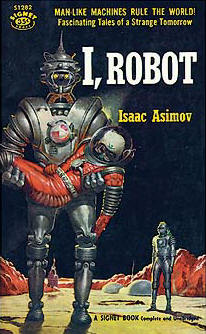

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics:

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics:

The term “Internet of Things” was first coined in 1999 by Kevin Ashton. It refers to the notion whereby physical objects of all kinds are equipped with small identifying devices and connected to a network. In essence: everything connected to anytime, anywhere by anyone. One of the potential benefits is that this would allow objects to be tracked, inventoried and status continuously monitored.

The term “Internet of Things” was first coined in 1999 by Kevin Ashton. It refers to the notion whereby physical objects of all kinds are equipped with small identifying devices and connected to a network. In essence: everything connected to anytime, anywhere by anyone. One of the potential benefits is that this would allow objects to be tracked, inventoried and status continuously monitored.

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen.

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen.

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well? Perhaps it’s time to re-think your social network when through it you know all about the stranger with whom you are sharing the elevator.

Perhaps it’s time to re-think your social network when through it you know all about the stranger with whom you are sharing the elevator. Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider.

Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider.

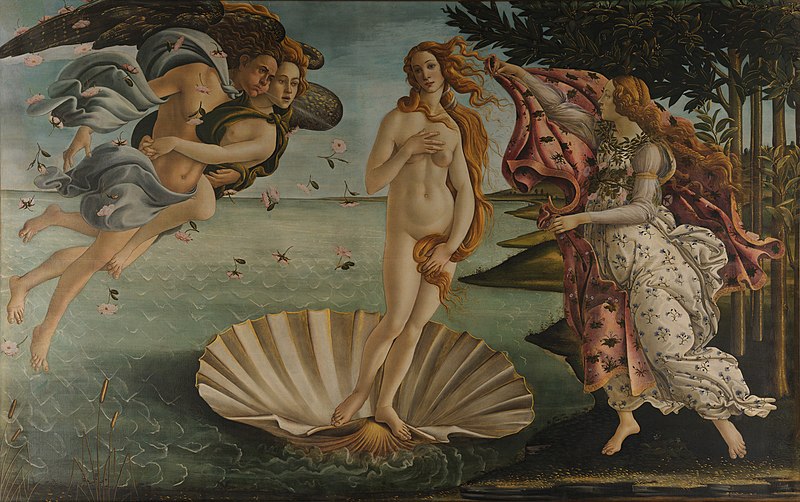

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”. Having just posted

Having just posted  The holidays approach, which for many means spending a more than usual amount of time with extended family and distant relatives. So, why talk face-to-face when you could text Great Uncle Aloysius instead?

The holidays approach, which for many means spending a more than usual amount of time with extended family and distant relatives. So, why talk face-to-face when you could text Great Uncle Aloysius instead?