Our collective addiction for purchasing anything, anytime may be wonderfully satisfying for a culture that collects objects and values unrestricted choice and instant gratification. However, it comes at a human cost. Not merely for those who produce our toys, clothes, electronics and furnishings in faraway, anonymous factories, but for those who get the products to our swollen mailboxes.

An intrepid journalist ventured to the very heart of the beast — an Amazon fulfillment center — to discover how the blood of internet commerce circulates; the Observer’s Carole Cadwalladr worked at Amazon’s warehouse, in Swansea, UK, for a week. We excerpt her tale below.

From the Guardian:

The first item I see in Amazon’s Swansea warehouse is a package of dog nappies. The second is a massive pink plastic dildo. The warehouse is 800,000 square feet, or, in what is Amazon’s standard unit of measurement, the size of 11 football pitches (its Dunfermline warehouse, the UK’s largest, is 14 football pitches). It is a quarter of a mile from end to end. There is space, it turns out, for an awful lot of crap.

But then there are more than 100m items on its UK website: if you can possibly imagine it, Amazon sells it. And if you can’t possibly imagine it, well, Amazon sells it too. To spend 10½ hours a day picking items off the shelves is to contemplate the darkest recesses of our consumerist desires, the wilder reaches of stuff, the things that money can buy: a One Direction charm bracelet, a dog onesie, a cat scratching post designed to look like a DJ’s record deck, a banana slicer, a fake twig. I work mostly in the outsize “non-conveyable” section, the home of diabetic dog food, and bio-organic vegetarian dog food, and obese dog food; of 52in TVs, and six-packs of water shipped in from Fiji, and oversized sex toys – the 18in double dong (regular-sized sex toys are shelved in the sortables section).

On my second day, the manager tells us that we alone have picked and packed 155,000 items in the past 24 hours. Tomorrow, 2 December – the busiest online shopping day of the year – that figure will be closer to 450,000. And this is just one of eight warehouses across the country. Amazon took 3.5m orders on a single day last year. Christmas is its Vietnam – a test of its corporate mettle and the kind of challenge that would make even the most experienced distribution supply manager break down and weep. In the past two weeks, it has taken on an extra 15,000 agency staff in Britain. And it expects to double the number of warehouses in Britain in the next three years. It expects to continue the growth that has made it one of the most powerful multinationals on the planet.

Right now, in Swansea, four shifts will be working at least a 50-hour week, hand-picking and packing each item, or, as the Daily Mail put it in an article a few weeks ago, being “Amazon’s elves” in the “21st-century Santa’s grotto”.

If Santa had a track record in paying his temporary elves the minimum wage while pushing them to the limits of the EU working time directive, and sacking them if they take three sick breaks in any three-month period, this would be an apt comparison. It is probably reasonable to assume that tax avoidance is not “constitutionally” a part of the Santa business model as Brad Stone, the author of a new book on Amazon, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, tells me it is in Amazon’s case. Neither does Santa attempt to bully his competitors, as Mark Constantine, the founder of Lush cosmetics, who last week took Amazon to the high court, accuses it of doing. Santa was not called before the Commons public accounts committee and called “immoral” by MPs.

For a week, I was an Amazon elf: a temporary worker who got a job through a Swansea employment agency – though it turned out I wasn’t the only journalist who happened upon this idea. Last Monday, BBC’s Panorama aired a programme that featured secret filming from inside the same warehouse. I wonder for a moment if we have committed the ultimate media absurdity and the show’s undercover reporter, Adam Littler, has secretly filmed me while I was secretly interviewing him. He didn’t, but it’s not a coincidence that the heat is on the world’s most successful online business. Because Amazon is the future of shopping; being an Amazon “associate” in an Amazon “fulfilment centre” – take that for doublespeak, Mr Orwell – is the future of work; and Amazon’s payment of minimal tax in any jurisdiction is the future of global business. A future in which multinational corporations wield more power than governments.

But then who hasn’t absent-mindedly clicked at something in an idle moment at work, or while watching telly in your pyjamas, and, in what’s a small miracle of modern life, received a familiar brown cardboard package dropping on to your doormat a day later. Amazon is successful for a reason. It is brilliant at what it does. “It solved these huge challenges,” says Brad Stone. “It mastered the chaos of storing tens of millions of products and figuring out how to get them to people, on time, without fail, and no one else has come even close.” We didn’t just pick and pack more than 155,000 items on my first day. We picked and packed the right items and sent them to the right customers. “We didn’t miss a single order,” our section manager tells us with proper pride.

At the end of my first day, I log into my Amazon account. I’d left my mum’s house outside Cardiff at 6.45am and got in at 7.30pm and I want some Compeed blister plasters for my toes and I can’t do it before work and I can’t do it after work. My finger hovers over the “add to basket” option but, instead, I look at my Amazon history. I made my first purchase, The Rough Guide to Italy, in February 2000 and remember that I’d bought it for an article I wrote on booking a holiday on the internet. It’s so quaint reading it now. It’s from the age before broadband (I itemise my phone bill for the day and it cost me £25.10), when Google was in its infancy. It’s littered with the names of defunct websites (remember Sir Bob Geldof’s deckchair.com, anyone?). It was a frustrating task and of pretty much everything I ordered, only the book turned up on time, as requested.

But then it’s a phenomenal operation. And to work in – and I find it hard to type these words without suffering irony seizure – a “fulfilment centre” is to be a tiny cog in a massive global distribution machine. It’s an industrialised process, on a truly massive scale, made possible by new technology. The place might look like it’s been stocked at 2am by a drunk shelf-filler: a typical shelf might have a set of razor blades, a packet of condoms and a My Little Pony DVD. And yet everything is systemised, because it has to be. It’s what makes it all the more unlikely that at the heart of the operation, shuffling items from stowing to picking to packing to shipping, are those flesh-shaped, not-always-reliable, prone-to-malfunctioning things we know as people.

It’s here, where actual people rub up against the business demands of one of the most sophisticated technology companies on the planet, that things get messy. It’s a system that includes unsystemisable things like hopes and fears and plans for the future and children and lives. And in places of high unemployment and low economic opportunities, places where Amazon deliberately sites its distribution centres – it received £8.8m in grants from the Welsh government for bringing the warehouse here – despair leaks around the edges. At the interview – a form-filling, drug- and alcohol-testing, general-checking-you-can-read session at a local employment agency – we’re shown a video. The process is explained and a selection of people are interviewed. “Like you, I started as an agency worker over Christmas,” says one man in it. “But I quickly got a permanent job and then promoted and now, two years later, I’m an area manager.”

Amazon will be taking people on permanently after Christmas, we’re told, and if you work hard, you can be one of them. In the Swansea/Neath/Port Talbot area, an area still suffering the body blows of Britain’s post-industrial decline, these are powerful words, though it all starts to unravel pretty quickly. There are four agencies who have supplied staff to the warehouse, and their reps work from desks on the warehouse floor. Walking from one training session to another, I ask one of them how many permanent employees work in the warehouse but he mishears me and answers another question entirely: “Well, obviously not everyone will be taken on. Just look at the numbers. To be honest, the agencies have to say that just to get people through the door.”

It does that. It’s what the majority of people in my induction group are after. I train with Pete – not his real name – who has been unemployed for the past three years. Before that, he was a care worker. He lives at the top of the Rhondda Valley, and his partner, Susan (not her real name either), an unemployed IT repair technician, has also just started. It took them more than an hour to get to work. “We had to get the kids up at five,” he says. After a 10½-hour shift, and about another hour’s drive back, before picking up the children from his parents, they got home at 9pm. The next day, they did the same, except Susan twisted her ankle on the first shift. She phones in but she will receive a “point”. If she receives three points, she will be “released”, which is how you get sacked in modern corporatese.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Amazon distribution warehouse in Milton Keynes, UK. Courtesy of Reuters / Dylan Martinez.

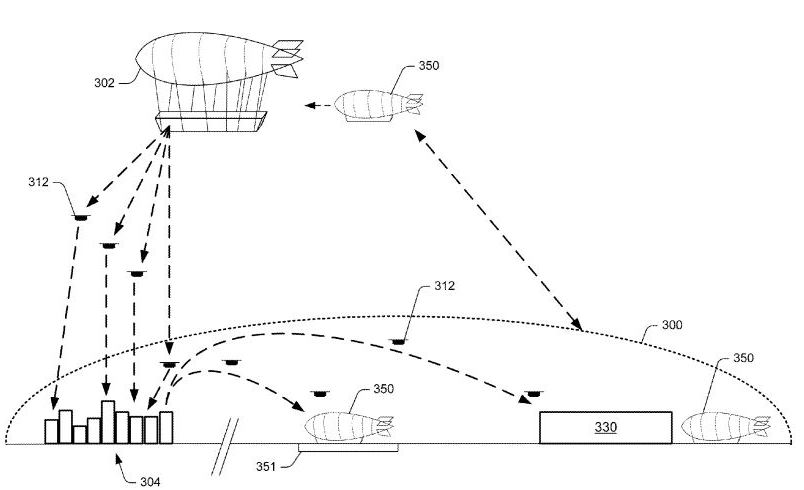

Soon courtesy of Amazon, Google and other retail giants, and of course lubricated by the likes of the ubiquitous UPS and Fedex trucks, you may be able to dispense with the weekly or even daily trip to the grocery store. Amazon is expanding a trial of its same-day grocery delivery service, and others are following suit in select local and regional tests.

Soon courtesy of Amazon, Google and other retail giants, and of course lubricated by the likes of the ubiquitous UPS and Fedex trucks, you may be able to dispense with the weekly or even daily trip to the grocery store. Amazon is expanding a trial of its same-day grocery delivery service, and others are following suit in select local and regional tests.

[div class=attrib]From Eurozine:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Eurozine:[end-div]