Having just posted this article on Christopher Hitchens earlier in the week we at theDiagonal are compelled to mourn and signal his departure. Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011 from pneumonia and complications from esophageal cancer.

Having just posted this article on Christopher Hitchens earlier in the week we at theDiagonal are compelled to mourn and signal his departure. Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011 from pneumonia and complications from esophageal cancer.

His incisive mind, lucid reason, quick wit and forceful skepticism will be sorely missed. Luckily, his written words, of which there are many, will live on.

Richard Dawkins writes of his fellow atheist:

Farewell, great voice. Great voice of reason, of humanity, of humour. Great voice against cant, against hypocrisy, against obscurantism and pretension, against all tyrants including God.

Author Ian McEwan writes of his close friend’s last weeks, which we excerpt below.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

The place where Christopher Hitchens spent his last few weeks was hardly bookish, but he made it his own. Close to downtown Houston, Texas is the medical centre, a cluster of high-rises like La Défense of Paris, or the City of London, a financial district of a sort, where the common currency is illness. This complex is one of the world’s great concentrations of medical expertise and technology. Its highest building, 40 or 50 storeys up, denies the possibility of a benevolent god – a neon sign proclaims from its roof a cancer hospital for children. This “clean-sliced cliff”, as Larkin puts it in his poem about a tower-block hospital, was right across the way from Christopher’s place – which was not quite as high, and adults only.

No man was ever as easy to visit in hospital. He didn’t want flowers and grapes, he wanted conversation, and presence. All silences were useful. He liked to find you still there when he woke from his frequent morphine-induced dozes. He wasn’t interested in being ill, the way most ill people are. He didn’t want to talk about it.

When I arrived from the airport on my last visit, he saw sticking out of my luggage a small book. He held out his hand for it – Peter Ackroyd‘s London Under, a subterranean history of the city. Then we began a 10-minute celebration of its author. We had never spoken of him before, and Christopher seemed to have read everything. Only then did we say hello. He wanted the Ackroyd, he said, because it was small and didn’t hurt his wrist to hold. But soon he was making pencilled notes in its margins. By that evening he’d finished it.

He could have written a review, but he was due to turn in a long piece on Chesterton. And so this was how it would go: talk about books and politics, then he dozed while I read or wrote, then more talk, then we both read. The intensive care unit room was crammed with flickering machines and sustaining tubes, but they seemed almost decorative. Books, journalism, the ideas behind both, conquered the sterile space, or warmed it, they raised it to the condition of a good university library. And they protected us from the bleak high-rise view through the plate glass windows, of that world, in Larkin’s lines, whose loves and chances “are beyond the stretch/Of any hand from here!”

In the afternoon I was helping him out of bed, the idea being that he was to take a shuffle round the nurses’ station to exercise his legs. As he leaned his trembling, diminished weight on me, I said, only because I knew he was thinking it, “Take my arm old toad …” He gave me that shifty sideways grin I remembered so well from healthy days. It was the smile of recognition, or one that anticipates in late afternoon an “evening of shame” – that is to say, pleasure, or, one of his favourite terms, “sodality”.

…

His unworldly fluency never deserted him, his commitment was passionate, and he never deserted his trade. He was the consummate writer, the brilliant friend. In Walter Pater’s famous phrase, he burned “with this hard gem-like flame”. Right to the end.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article here.[end-div]

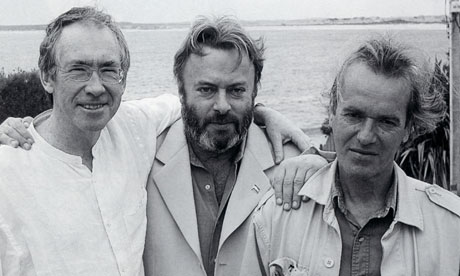

[div class=attrib]Image: Christopher Hitchens with Ian McEwan (left) and Martin Amis in Uruguay, posing for a picture which appeared in his memoirs, Hitch 22. Courtesy of Guardian / PR.[end-div]