At any point in time, every major religion seems to be home to a handful of outspoken radicals who act as both standard-bearers and lightening rods for the broader movement. And, atheism is no different. If you Google “atheist” it is highly likely that the most frequent hits will highlight Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, our beloved, and recently departed, Chris Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins.

At any point in time, every major religion seems to be home to a handful of outspoken radicals who act as both standard-bearers and lightening rods for the broader movement. And, atheism is no different. If you Google “atheist” it is highly likely that the most frequent hits will highlight Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, our beloved, and recently departed, Chris Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins.

Of course, they all have their very own, very different approaches to prosletyzing — that is, if atheists are indeed allowed to do such a thing. Hitchens, for example, used his unsurpassed erudition, elephantine memory and linguistic eloquence, and logic, to crush contrary opinion in a relentless but very thoughtful and charming way. Dawkins on the other hand comes across as more arrogant and impatient. He’s on a mission to save the world from the believers.

From the Guardian:

On the top floor of Random House’s offices in London, the world’s number one thinker – according to Prospect magazine’s annual poll – walks in from the roof terrace and shakes my hand. Richard Dawkins is a trim 72-year-old with one of those faces that, no matter the accumulation of lines, will always draw the adjective “boyish”.

There’s a smoothness to the way he carries himself – a touch of the Nigel Havers – that could no doubt be construed as an arrogance befitting his intellectual status, but in conversation he is restrained, even hesitant, and faultlessly modest throughout our interview.

Perhaps the renowned evolutionary biologist and the world’s most famous atheist was feeling especially cautious. The day before I met him he had become embroiled in a Twitterstorm, which grew into a broader media monsoon, after he had tweeted the following: “All the world’s Muslims have fewer Nobel prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge. They did great things in the middle ages, though.”

He defended himself in the ensuing furore by saying that he was merely stating a fact. And it’s true, it was a fact. Many objected that it was a fact used to demonise Muslims, that it was racist (Dawkins responded by pointing out that Islam is not a race), and that, out of context, it was, at the very least, mischievous and misleading.

I returned later to this dispute, but first of all we got down to discussing his memoir, An Appetite for Wonder, a sort of portrait of the scientist as a young man. The first of two volumes, it takes us from boyhood to the publication of his landmark bestseller, The Selfish Gene. The story begins with his colonial childhood in Kenya and Nyasaland (now Malawi), and is full of dusty anecdotes of our young hero rummaging without a care in the great African outdoors. Does he look back with nostalgia at that now largely disappeared way of life?

“Yes,” he says slowly, as if watchful for hidden traps. “It’s now unfashionable and in many ways it’s something we British have to live down. But yes, there is a nostalgia for it and, although I was never in India, I get it reading novels of the Raj. It’s a lost era that you can’t help having a certain affection for, even if you disapprove politically.”

His parents were hardy, practical types, unflustered by war or life in the bush or, it seems, anything else. His father was a botanist, working in the agricultural office in Nyasaland, so Dawkins grew up in a family that took a scientific interest in living organisms, though he insists he never inherited his parents’ extensive knowledge of flora and fauna.

He moved to England when he was nine and went through a very typical public school experience for the era, except that he managed to fend off the sexual predations of older boys. Other than in relation to genetic research, sex doesn’t raise its titillating head at all in the book – apart from one occasion. We learn that at the ripe age of 22 he lost his virginity to a cellist in London. She “removed her skirt in order to play to me in her bedsitter (you can’t play the cello in a tight skirt) – and then removed everything else.”

But that’s all that Dawkins allows in terms of romance.

“Well that was a little token to say, ‘This is all you’re going to get,’?” he says firmly. “I wanted to announce that this is not going to be that kind of autobiography.”

Why not? “Fear of betraying confidences,” he says, shifting in his chair. “These things are private. Some people let it all hang out but I prefer not to.”

You can say that again. Dawkins may have an appetite for wonder, but he is positively anorexic when it comes to personal revelation. Perhaps the most confessional section – and it can hardly be called exposing – deals with his years teaching at Berkeley in the late 60s, when the campus was a hotbed of countercultural revolt. Dawkins took part in protests against the Vietnam war, of which he remains proud, but also got caught up in a local militant initiative to take over some university waste ground and turn it into a “people’s park”. “With hindsight,” he writes, “it was a trumped-up excuse for radical activism for its own sake.”

I suggest that radical movements invariably function on peer pressure and he agrees that he succumbed to the impulse to belong. “There was a sort of feeling of flower power and drugs,” he says. “I never actually took drugs, oddly enough. I never had the opportunity. But the music of the time and the atmosphere – there was a feeling of loyalty to the protesters: these are my people. The same people who marched against the Vietnam war marched for the people’s park and it was an automatic decision to join them. One should be more independent-minded than that.”

That’s Dawkins at his most self-reflective. He avoids any details of interest about his first marriage – to the ethologist Marian Stamp. And according to him, he is unlikely to be any more forthcoming in the second volume about his second marriage to Eve Barham, or his third to the actress Lalla Ward, a former assistant to Dr Who, who was introduced to him by his late friend Douglas Adams.

The couple live in Oxford, where Dawkins has resided almost all of his adult life, and where he spent 13 years until his retirement in 2008 as the professor for public understanding of science. As he was free in that role to pursue his own interests, he says his “nominal retirement” has made no difference at all.

The memoir is strong on the professional excitement of his early years as an academic, but it assiduously sidesteps the rivalries and disputes that mark even the most unremarkable scientific careers, let alone one as distinguished as Dawkins’s. He didn’t want any score settling, he says, or to “appear hostile”.

So although he notes that the biologists Richard Lewontin and Steven Rose were two of the rare voices who criticised The Selfish Gene on its widely acclaimed publication in 1976, he fails to discuss their arguments or his thoughts on them, other than to say that both came from the “political left”. Did he think their case against him was political rather than scientific?

“Yes, I think politics,” he says after another anxious pause. “I actually wrote a fairly savage review of the joint book they produced later [Not in Our Genes] which I suppose I’ll probably mention in volume two.” He weighs his words again and then adds, “It was sarcastic rather than savage.”

Dawkins seems determined in both the memoir and our interview to present a calm, conciliatory side to his character that has not always been associated with his public image. Later the photographer, Andy Hall, will tell me that Dawkins requested to look at the screen on Hall’s camera to see what he had captured during the shoot. “You’ve made me look too harsh,” complained the biologist.

Hall told him he was merely giving him appropriate gravitas.

“I don’t want fucking gravitas,” Dawkins snapped. “I want humanity.”

One senses that for all the recognition he’s garnered – the world’s leading intellectual, the bestselling books, the rapt audiences etc – Dawkins would like to be a little more loved. I ask him if he thinks he’s misunderstood by the media and the general public.

Read the entire article here.

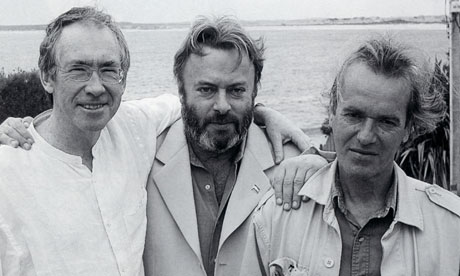

Image: Richard Dawkins, 2010. Courtesy of Cooper Union / Wikipedia.

Having just posted

Having just posted