Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins sprang to the public’s attention via his immensely popular book The Selfish Gene. Since its publication almost 40 years ago, its author has assumed the unofficial mantle of Atheist-In-Chief. His passionate and impatient defense — some would call it crusading offense — of all things godless has rubbed many the wrong way, including numerous unbelievers. That said, his reasoning remains crystal clear and his focus laser-like. I just wish he would stay away from Twitter.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins sprang to the public’s attention via his immensely popular book The Selfish Gene. Since its publication almost 40 years ago, its author has assumed the unofficial mantle of Atheist-In-Chief. His passionate and impatient defense — some would call it crusading offense — of all things godless has rubbed many the wrong way, including numerous unbelievers. That said, his reasoning remains crystal clear and his focus laser-like. I just wish he would stay away from Twitter.

Check out his foundation here.

From the Guardian:

In Dublin, not long ago, Richard Dawkins visited a steakhouse called Darwin’s. He was in town to give a talk on the origins of life at Trinity College with the American physicist Lawrence Krauss. In the restaurant, a large model gorilla squatted in a corner and a series of sepia paintings of early man hung in the dining room – though, Dawkins pointed out, not quite in the right chronological order. A space by the bar had been refitted to resemble the interior of the Beagle, the vessel on which Charles Darwin sailed to South America in 1831 and conceived his theory of natural selection. “Oh look at this!” Dawkins said, examining the decor. “It’s terrific! Oh, wonderful.”

Over the years, Dawkins, a zoologist by training, has expressed admiration for Darwin in the way a schoolboy might worship a sporting giant. In his first memoir, Dawkins noted the “serendipitous realisation” that his full name – Clinton Richard Dawkins – shared the same initials as Charles Robert Darwin. He owns a prized first edition of On The Origin of Species, which he can quote from memory. For Dawkins, the book is totemic, the founding text of his career. “It’s such a thorough, unanswerable case,” he said one afternoon. “[Darwin] called it one long argument.” As a description of Dawkins’s own life, particularly its late phase, “one long argument” serves fairly well. As the global face of atheism over the last decade, Dawkins has ratcheted up the rhetoric in his self-declared war against religion. He is the general who chooses to fight on the front line – whose scorched-earth tactics have won him fervent admirers, and ferocious enemies. What is less clear, however, is whether he is winning.

Over dinner – chicken for Dawkins, steak for everyone else – he spoke little. He was anxious to leave early in order to discuss the format of the event with Krauss. Though Dawkins gives a talk roughly once a fortnight, he still obsessively overprepares. On this occasion, there was no need – he and Krauss had put on a similar show the night before at the University of Ulster in Belfast. They had also appeared on a radio talkshow, during which they had attempted to debate a creationist (an “idiot”, in Dawkins’s terminology). “She simply tried to shout down everything Lawrence and I said. So she was in effect going la la la la la.” Dawkins stuck his fingers in his ears as he sang.

Krauss and Dawkins have toured frequently as a double act, partners in a global quest to broadcast the wonder of science and the nonexistence of God. Dawkins has been on this mission ever since 1976, when he published The Selfish Gene, the book that made him famous, which has now sold over a million copies. Since then, he has written another 10 influential books on science and evolution, plus The God Delusion, his atheist blockbuster, and become the most prominent of the so-called New Atheists – a group of writers, including Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris, who published anti-religion polemics in the years after 9/11.

An hour or so after dinner, the Burke Theatre in Trinity College, a large modern lecture hall with banked seating, was full. After separate presentations, Krauss and Dawkins conversed freely, swapping ideas on the origins of life. As he spoke, Dawkins took on a grandfatherly air, as though passing on hard-earned wisdom. He has always sought to inject beauty into biology, and his voice wavered with emotion as he shifted from dry fact to lyrical metaphor.

Dawkins has the stately confidence of one who has spent half a life behind a lectern. He has aged well, thanks to the determined jaw and carved cheekbones of a 1950s matinee idol. His hair remains in the style that has served him for 70 years, a lopsided sweep. A prominent brow and hawkish stare give him a look of constant urgency, as though he is waiting for everyone to catch up. In Dublin, his outfit was academic-on-tour: jacket, woolly jumper and tie, one of a collection hand-painted by his wife, Lalla Ward, which depict penguins, fish, birds of prey.

At the end of the Trinity event, a crowd of about 40 audience members descended on to the stage, clutching books to be signed. Dawkins eventually retreated into the wings to avoid a crush. One young schoolteacher lingered in the hallway long after the rest of the audience had left, in the hope of shaking Dawkins’s hand. Earlier that day, Dawkins had expressed bewilderment at his own celebrity. “I find the epidemic of selfies disconcerting,” he said. “It’s always, ‘one quick photo.’ One quick. But it never is.” Though he is used to receiving a steady flow of letters from fans of The God Delusion and new converts to atheism, he does not perceive himself as a figurehead. “I don’t need to say if I think of myself as a leader,” he said a few weeks later. “I simply need to say the book has sold three million copies.”

Dawkins turned 74 in March this year. To celebrate, he had dinner with Ward at Cherwell Boathouse, a smart restaurant overlooking the river in Oxford; the occasion was marred only slightly by a loud-voiced fellow diner, Dawkins recalled, “who quacked like Donald Duck”. An academic of his eminence could, by now, have eased into a distinguished late period: more books, the odd speech, master of an Oxford college, a gentle tending to his legacy. Though he is in a retrospective phase – one memoir published, a second on its way later this year – peaceful retreat from public life has not been the Dawkins way. “Some people might say why don’t you just get on with gardening,” he said. “I think [there’s a] passion for truth and a passion for justice that doesn’t allow me to do that.”

Instead, Dawkins remains indefatigably active. He rarely takes a holiday, but travels frequently to give talks – in the last four months he has been to Ireland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Brazil. Though he says he prefers to speak about science, God inevitably looms. “I suppose some of what I do is an attempt to change people’s minds about religion,” he said, with some understatement, between events in Ireland. “And I do think that’s a politically important thing to be doing.” For Dawkins, who describes his own politics as “vaguely left”, this means a concern for the state of the world, and a desire, ultimately, to eradicate religion from society. In his mission, Dawkins is still, at heart, a teacher. “I would like to leave the world a better place,” he said. “I like to think my science books have had a positive educational effect, but I also want to leave the world a better place in influencing opinion in other fields where there is illogic, obscurantism, pretension.” Religious faith, for Dawkins, is above all a sign of faulty thinking, of ignorance; he wants to educate the ill-informed out of their mistakes. He sees religion, as he once put it on Twitter, as “an organised licence to be acceptably stupid”.

The two strands of Dawkins’s mission – promoting science, demolishing religion – are intended to be complementary. “If they are antagonistic to each other, that would be regrettable,” he said, “but I don’t see why they should be.” But antagonism is part of Dawkins’s daily life. “I suppose some of the passions that I show are more appropriate to a young man than somebody of my age.” Since his arrival on Twitter in 2008, his public pronouncements have become more combative – and, at times, flamboyantly irritable: “How dare you force your dopey unsubstantiated superstitions on innocent children too young to resist?,” he tweeted last June. “How DARE you?”

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins)June 10, 2014

How dare you force your dopey unsubstantiated superstitions on innocent children too young to resist? How DARE you?

Read the entire story here.

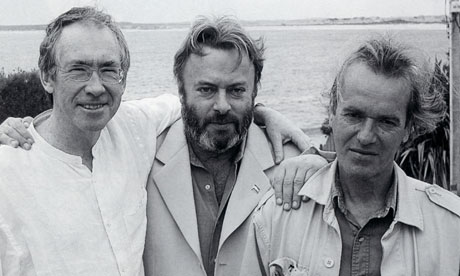

Image: Richard Dawkins, 34th annual conference of American Atheists (2008). Public domain.

Having just posted

Having just posted