[div class=attrib]From BigThink:[end-div]

Today, I’d like to revisit one of the most well-known experiments in social psychology: Solomon Asch’s lines study. Let’s look once more at his striking findings on the power of group conformity and consider what they mean now, more than 50 years later, in a world that is much changed from Asch’s 1950s America.

How long are these lines? I don’t know until you tell me.

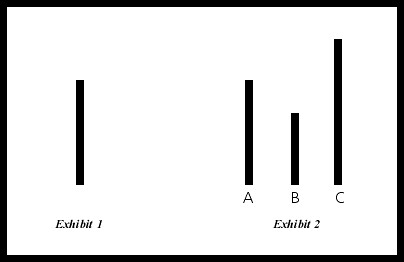

In the 1950s, Solomon Asch conducted a series of studies to examine the effects of peer pressure, in as clear-cut a setting as possible: visual perception. The idea was to see if, when presented with lines of differing lengths and asked questions about the lines (Which was the longest? Which corresponded to a reference line of a certain length?), participants would answer with the choice that was obviously correct – or would fall sway to the pressure of a group that gave an incorrect response. Here is a sample stimulus from one of the studies:

Which line matches the reference line? It seems obvious, no? Now, imagine that you were in a group with six other people – and they all said that it was, in fact, Line B. Now, you would have no idea that you were the only actual participant and that the group was carefully arranged with confederates, who were instructed to give that answer and were seated in such a way that they would answer before you. You’d think that they, like you, were participants in the study – and that they all gave what appeared to you to be a patently wrong answer. Would you call their bluff and say, no, the answer is clearly Line A? Are you all blind? Or, would you start to question your own judgment? Maybe it really is Line B. Maybe I’m just not seeing things correctly. How could everyone else be wrong and I be the only person who is right?

We don’t like to be the lone voice of dissent

While we’d all like to imagine that we fall into the second camp, statistically speaking, we are three times more likely to be in the first: over 75% of Asch’s subjects (and far more in the actual condition given above) gave the wrong answer, going along with the group opinion.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq.

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq. [div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From Institute of Physics:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Institute of Physics:[end-div] [div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div] Imagine a world without books; you’d have to commit useful experiences, narratives and data to handwritten form and memory.Imagine a world without the internet and real-time search; you’d have to rely on a trusted expert or a printed dictionary to find answers to your questions. Imagine a world without the written word; you’d have to revert to memory and oral tradition to pass on meaningful life lessons and stories.

Imagine a world without books; you’d have to commit useful experiences, narratives and data to handwritten form and memory.Imagine a world without the internet and real-time search; you’d have to rely on a trusted expert or a printed dictionary to find answers to your questions. Imagine a world without the written word; you’d have to revert to memory and oral tradition to pass on meaningful life lessons and stories. One of the most fascinating and (in)famous experiments in social psychology began in the bowels of Stanford University 40 years ago next month. The experiment intended to evaluate how people react to being powerless. However, on conclusion it took a broader look at role assignment and reaction to authority.

One of the most fascinating and (in)famous experiments in social psychology began in the bowels of Stanford University 40 years ago next month. The experiment intended to evaluate how people react to being powerless. However, on conclusion it took a broader look at role assignment and reaction to authority. [div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs / BigThink:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs / BigThink:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From ReadWriteWeb:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From ReadWriteWeb:[end-div] Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process.

Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process. David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies.

David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies. The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge:

The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge:  Editor’s Note: We are republishing this article by Paul Dirac from the May 1963 issue of Scientific American, as it might be of interest to listeners to the June 24, 2010, and June 25, 2010 Science Talk podcasts, featuring award-winning writer and physicist Graham Farmelo discussing The Strangest Man, his biography of the Nobel Prize-winning British theoretical physicist.

Editor’s Note: We are republishing this article by Paul Dirac from the May 1963 issue of Scientific American, as it might be of interest to listeners to the June 24, 2010, and June 25, 2010 Science Talk podcasts, featuring award-winning writer and physicist Graham Farmelo discussing The Strangest Man, his biography of the Nobel Prize-winning British theoretical physicist. We have, then, the development from the three-dimensional picture of the world to the four-dimensional picture. The reader will probably not be happy with this situation, because the world still appears three-dimensional to his consciousness. How can one bring this appearance into the four-dimensional picture that Einstein requires the physicist to have?

We have, then, the development from the three-dimensional picture of the world to the four-dimensional picture. The reader will probably not be happy with this situation, because the world still appears three-dimensional to his consciousness. How can one bring this appearance into the four-dimensional picture that Einstein requires the physicist to have? For the first time, scientists have created life from scratch – well, sort of.

For the first time, scientists have created life from scratch – well, sort of.  Edward M. Marcotte is looking for drugs that can kill

Edward M. Marcotte is looking for drugs that can kill