“I don’t see the point in measuring life in time any more… I would rather measure it in terms of what I actually achieve. I’d rather measure it in terms of making a difference, which I think is a much more valid and pragmatic measure.”

These are the inspiring and insightful words of 19 year-old, Stephen Sutton, from Birmingham in Britain, about a week before he died from bowel cancer. His upbeat attitude and selflessness during his last days captured the hearts and minds of the nation, and he raised around $5½ million for cancer charities in the process.

From the Guardian:

Few scenarios can seem as cruel or as bleak as a 19-year-old boy dying of cancer. And yet, in the case of Stephen Sutton, who died peacefully in his sleep in the early hours of Wednesday morning, it became an inspiring, uplifting tale for millions of people.

Sutton was already something of a local hero in Birmingham, where he was being treated, but it was an extraordinary Facebook update in April that catapulted him into the national spotlight.

“It’s a final thumbs up from me,” he wrote, accompanied by a selfie of him lying in a sickbed, covered in drips, smiling cheerfully with his thumbs in the air. “I’ve done well to blag things as well as I have up till now, but unfortunately I think this is just one hurdle too far.”

It was an extraordinary moment: many would have forgiven him being full of rage and misery. And yet here was a simple, understated display of cheerful defiance.

Sutton had originally set a fundraising target of £10,000 for the Teenage Cancer Trust. But the emotional impact of that selfie was so profound that, in a matter of days, more than £3m was donated.

He made a temporary recovery that baffled doctors; he explained that he had “coughed up” a tumour. And so began an extraordinary dialogue with his well-wishers.

To his astonishment, nearly a million people liked his Facebook page and tens of thousands followed him on Twitter. It is fashionable to be downbeat about social media: to dismiss it as being riddled with the banal and the narcissistic, or for stripping human interaction of warmth as conversations shift away from the “real world” to the online sphere.

But it was difficult not to be moved by the online response to Stephen’s story: a national wave of emotion that is not normally forthcoming for those outside the world of celebrity.

His social-media updates were relentlessly upbeat, putting those of us who have tweeted moaning about a cold to shame. “Just another update to let everyone know I am still doing and feeling very well,” he reassured followers less than a week before his death. “My disease is very advanced and will get me eventually, but I will try my damn hardest to be here as long as possible.”

Sutton was diagnosed with bowel cancer in September 2010 when he was 15; tragically, he had been misdiagnosed and treated for constipation months earlier.

But his response was unabashed positivity from the very beginning, even describing his diagnosis as a “good thing” and a “kick up the backside”.

The day he began chemotherapy, he attended a party dressed as a granny – he was so thin and pale, he said, that he was “quite convincing”. He refused to take time off school, where he excelled.

When he was diagnosed as terminally ill two years later, he set up a Facebook page with a bucket list of things he wanted to achieve, including sky-diving, crowd-surfing in a rubber dinghy, and hugging an animal bigger than him (an elephant, it turned out).

But it was his fundraising for cancer research that became his passion, and his efforts will undoubtedly transform the lives of some of the 2,200 teenagers and young adults diagnosed with cancer each year.

The Teenage Cancer Trust on Wednesday said it was humbled and hugely grateful for his efforts, with donations still ticking up and reaching £3.34m by mid-afternoon .

His dream had been to become a doctor. With that ambition taken from him, he sought and found new ways to help people. “Spreading positivity” was another key aim. Four days ago, he organised a National Good Gestures Day, in Birmingham, giving out “free high-fives, hugs, handshakes and fist bumps”.

Indeed, it was not just money for cancer research that Sutton was after. He became an evangelist for a new approach to life.

“I don’t see the point in measuring life in time any more,” he told one crowd. “I would rather measure it in terms of what I actually achieve. I’d rather measure it in terms of making a difference, which I think is a much more valid and pragmatic measure.”

By such a measure, Sutton could scarcely have lived a longer, richer and more fulfilling life.

Read the entire story here.

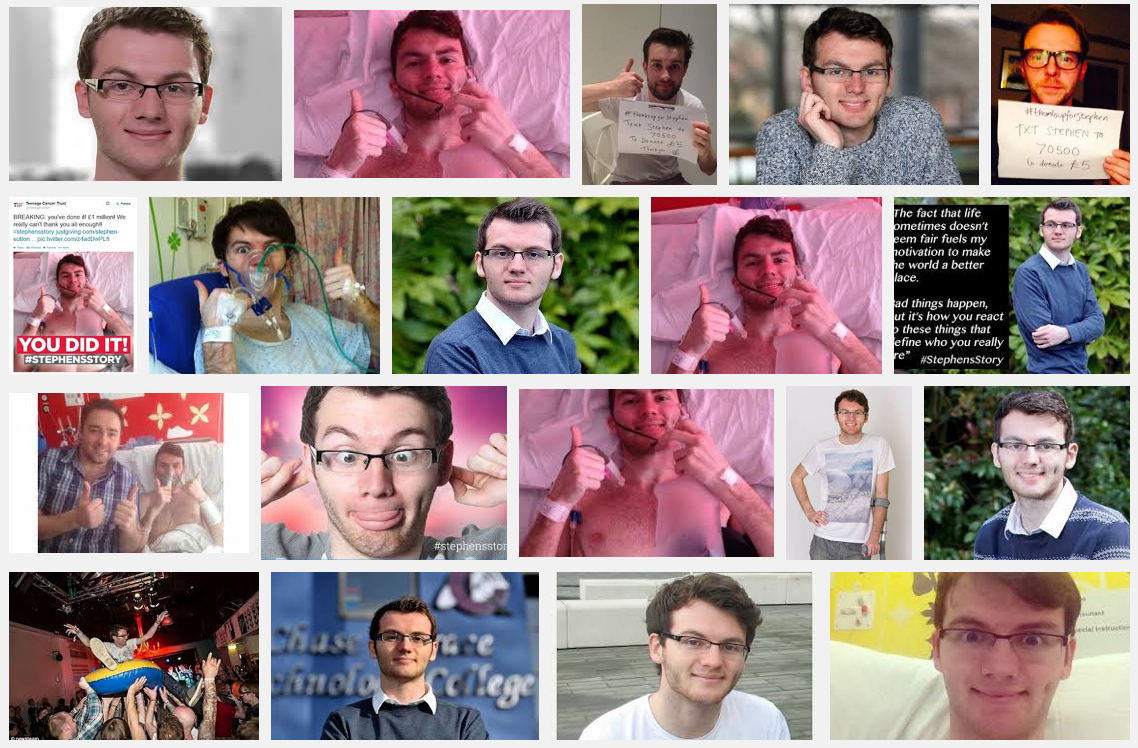

Image: Stephen Sutton. Courtesy of Google Search.

The illustrious Vaccinia virus may well have an Act Two in its future.

The illustrious Vaccinia virus may well have an Act Two in its future. The title could be mistaken for a dark and violent crime novel from the likes of (Stieg) Larrson, Nesbø, Sjöwall-Wahlöö, or Henning Mankell. But, this story is somewhat more mundane, though much more consequential. It’s a story about a Swedish cancer killer.

The title could be mistaken for a dark and violent crime novel from the likes of (Stieg) Larrson, Nesbø, Sjöwall-Wahlöö, or Henning Mankell. But, this story is somewhat more mundane, though much more consequential. It’s a story about a Swedish cancer killer.