Attend a wedding. Gather the hundred or so guests, and take their blood. Take samples that is. Then, measure the levels of a hormone called oxytocin. This is where neuroeconomist Paul Zak’s story beings — around a molecular messenger thought to be responsible for facilitating trust and empathy in all our intimate relationships.

[div class=attrib]From “The Moral Molecule” by Paul J. Zak, to be published May 10, courtesy of the Wall Street Journal:[end-div]

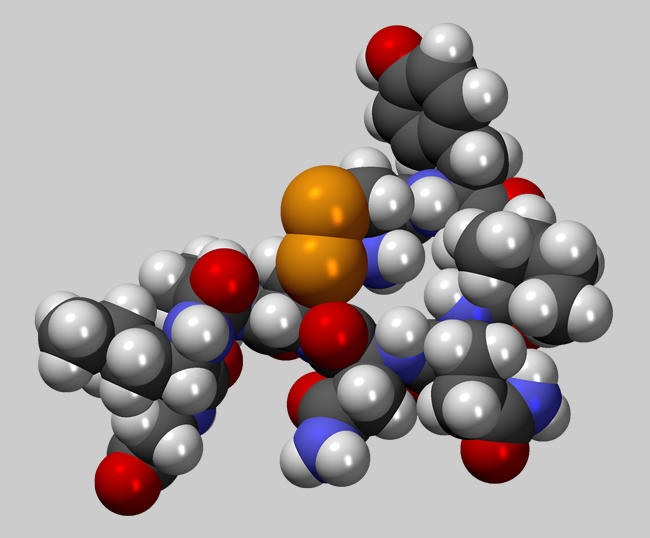

Could a single molecule—one chemical substance—lie at the very center of our moral lives?

Research that I have done over the past decade suggests that a chemical messenger called oxytocin accounts for why some people give freely of themselves and others are coldhearted louts, why some people cheat and steal and others you can trust with your life, why some husbands are more faithful than others, and why women tend to be nicer and more generous than men. In our blood and in the brain, oxytocin appears to be the chemical elixir that creates bonds of trust not just in our intimate relationships but also in our business dealings, in politics and in society at large.

Known primarily as a female reproductive hormone, oxytocin controls contractions during labor, which is where many women encounter it as Pitocin, the synthetic version that doctors inject in expectant mothers to induce delivery. Oxytocin is also responsible for the calm, focused attention that mothers lavish on their babies while breast-feeding. And it is abundant, too, on wedding nights (we hope) because it helps to create the warm glow that both women and men feel during sex, a massage or even a hug.

Since 2001, my colleagues and I have conducted a number of experiments showing that when someone’s level of oxytocin goes up, he or she responds more generously and caringly, even with complete strangers. As a benchmark for measuring behavior, we relied on the willingness of our subjects to share real money with others in real time. To measure the increase in oxytocin, we took their blood and analyzed it. Money comes in conveniently measurable units, which meant that we were able to quantify the increase in generosity by the amount someone was willing to share. We were then able to correlate these numbers with the increase in oxytocin found in the blood.

Later, to be certain that what we were seeing was true cause and effect, we sprayed synthetic oxytocin into our subjects’ nasal passages—a way to get it directly into their brains. Our conclusion: We could turn the behavioral response on and off like a garden hose. (Don’t try this at home: Oxytocin inhalers aren’t available to consumers in the U.S.)

More strikingly, we found that you don’t need to shoot a chemical up someone’s nose, or have sex with them, or even give them a hug in order to create the surge in oxytocin that leads to more generous behavior. To trigger this “moral molecule,” all you have to do is give someone a sign of trust. When one person extends himself to another in a trusting way—by, say, giving money—the person being trusted experiences a surge in oxytocin that makes her less likely to hold back and less likely to cheat. Which is another way of saying that the feeling of being trusted makes a person more…trustworthy. Which, over time, makes other people more inclined to trust, which in turn…

If you detect the makings of an endless loop that can feed back onto itself, creating what might be called a virtuous circle—and ultimately a more virtuous society—you are getting the idea.

Obviously, there is more to it, because no one chemical in the body functions in isolation, and other factors from a person’s life experience play a role as well. Things can go awry. In our studies, we found that a small percentage of subjects never shared any money; analysis of their blood indicated that their oxytocin receptors were malfunctioning. But for everyone else, oxytocin orchestrates the kind of generous and caring behavior that every culture endorses as the right way to live—the cooperative, benign, pro-social way of living that every culture on the planet describes as “moral.” The Golden Rule is a lesson that the body already knows, and when we get it right, we feel the rewards immediately.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]CPK model of the Oxitocin molecule C43H66N12O12S2. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]