The internet and its user-friendly interface, the World Wide Web (Web), was founded on the principle of openness. The acronym soup of standards, such as TCP/IP, HTTP and HTML, paved the way for unprecedented connectivity and interoperability. Anyone armed with a computer and a connection, adhering to these standards, could now connect and browse and share data with any one else.

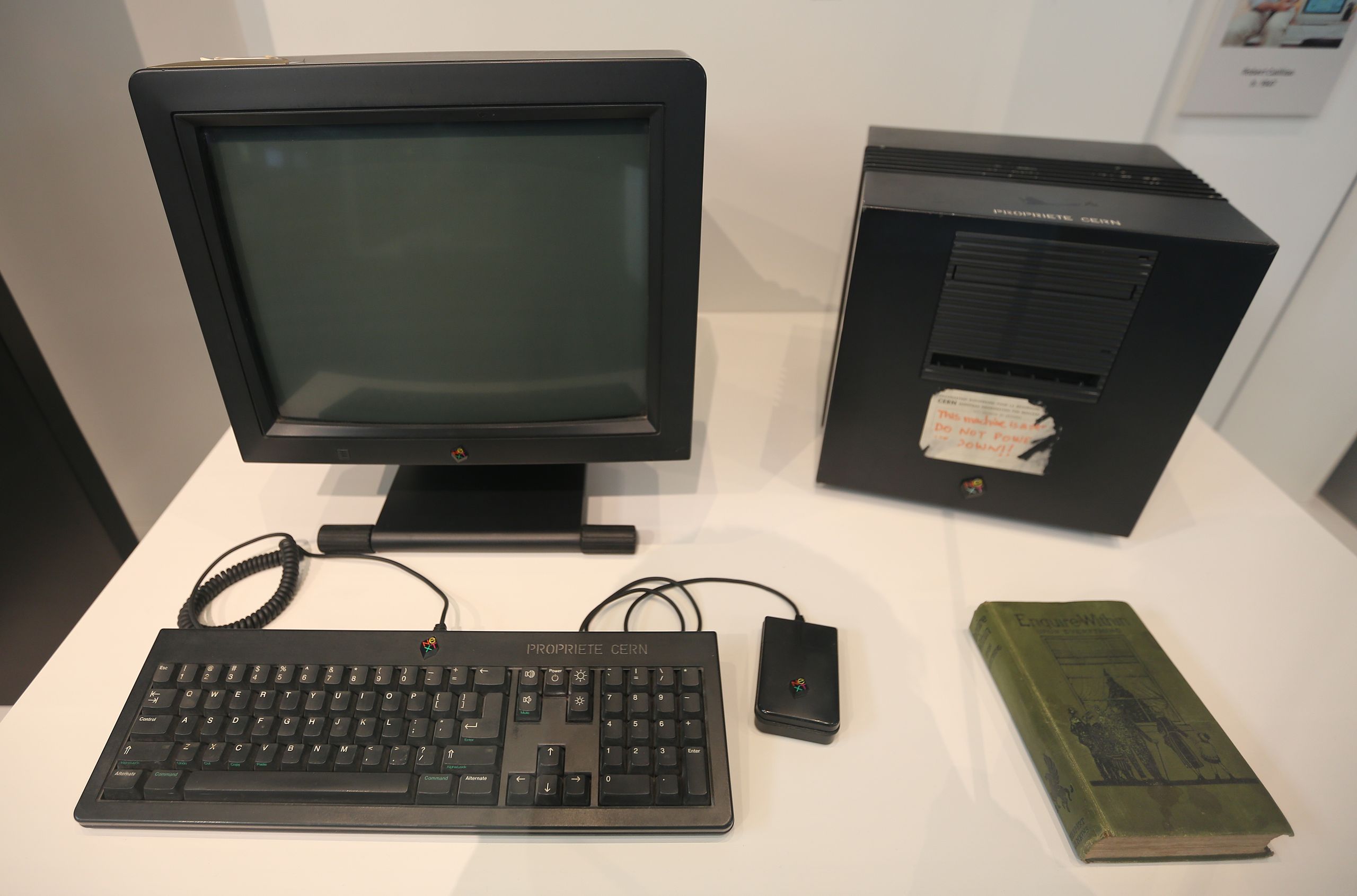

This is a simplified view of Sir Tim Berners-Lee vision for the Web in 1989 — the same year that brought us Seinfeld and The Simpsons. Berners-Lee invented the Web. His invention fostered an entire global technological and communications revolution over the next quarter century.

However, Berners-Lee did something much more important. Rather than keeping the Web to himself and his colleagues, and turning to Silicon Valley to found and fund the next billion dollar startup, he pursued a path to give the ideas and technologies away. Critically, the open standards of the internet and Web enabled countless others to innovate and to profit.

One of the innovators to reap the greatest rewards from this openness is Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. Yet, in the ultimate irony, Facebook has turned the Berners-Lee model of openness and permissionless innovation on its head. It’s billion-plus users are members of a private, corporate-controlled walled garden. Innovation, to a large extent, is now limited by the whims of Facebook. Increasingly so, open innovation on the internet is stifled and extinguished by the constraints manufactured and controlled for Facebook’s own ends. This makes Zuckerberg’s vision of making the world “more open and connected” thoroughly laughable.

From the Guardian:

If there were a Nobel prize for hypocrisy, then its first recipient ought to be Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook boss. On 23 August, all his 1.7 billion users were greeted by this message: “Celebrating 25 years of connecting people. The web opened up to the world 25 years ago today! We thank Sir Tim Berners-Lee and other internet pioneers for making the world more open and connected.”

Aw, isn’t that nice? From one “pioneer” to another. What a pity, then, that it is a combination of bullshit and hypocrisy. In relation to the former, the guy who invented the web, Tim Berners-Lee, is as mystified by this “anniversary” as everyone else. “Who on earth made up 23 August?” he asked on Twitter. Good question. In fact, as the Guardian pointed out: “If Facebook had asked Berners-Lee, he’d probably have told them what he’s been telling people for years: the web’s 25th birthday already happened, two years ago.”

“In 1989, I delivered a proposal to Cern for the system that went on to become the worldwide web,” he wrote in 2014. It was that year, not this one, that he said we should celebrate as the web’s 25th birthday.

It’s not the inaccuracy that grates, however, but the hypocrisy. Zuckerberg thanks Berners-Lee for “making the world more open and connected”. So do I. What Zuck conveniently omits to mention, though, is that he is embarked upon a commercial project whose sole aim is to make the world more “connected” but less open. Facebook is what we used to call a “walled garden” and now call a silo: a controlled space in which people are allowed to do things that will amuse them while enabling Facebook to monetise their data trails. One network to rule them all. If you wanted a vision of the opposite of the open web, then Facebook is it.

The thing that makes the web distinctive is also what made the internet special, namely that it was designed as an open platform. It was designed to facilitate “permissionless innovation”. If you had a good idea that could be realised using data packets, and possessed the programming skills to write the necessary software, then the internet – and the web – would do it for you, no questions asked. And you didn’t need much in the way of financial resources – or to ask anyone for permission – in order to realise your dream.

An open platform is one on which anyone can build whatever they like. It’s what enabled a young Harvard sophomore, name of Zuckerberg, to take an idea lifted from two nice-but-dim oarsmen, translate it into computer code and launch it on an unsuspecting world. And in the process create an empire of 1.7 billion subjects with apparently limitless revenues. That’s what permissionless innovation is like.

The open web enabled Zuckerberg to do this. But – guess what? – the Facebook founder has no intention of allowing anyone to build anything on his platform that does not have his express approval. Having profited mightily from the openness of the web, in other words, he has kicked away the ladder that elevated him to his current eminence. And the whole thrust of his company’s strategy is to persuade billions of future users that Facebook is the only bit of the internet they really need.

Read the entire article here.

Image: The NeXT Computer used by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN. Courtesy: Science Museum, London. GFDL CC-BY-SA.

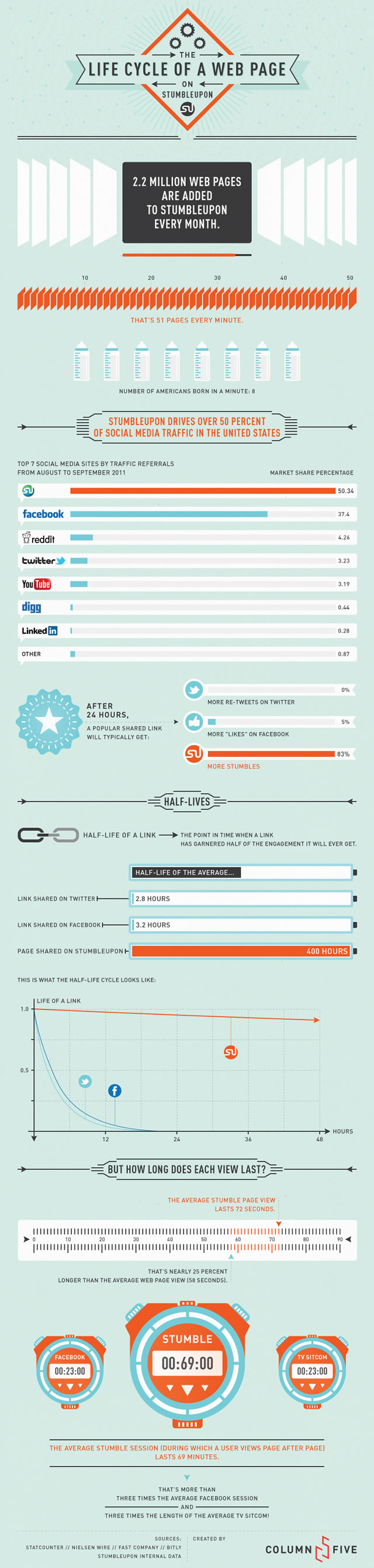

By most accounts the internet is home to around 650 million websites, of which around 200 million are active. About 8,000 new websites go live every hour of every day.

By most accounts the internet is home to around 650 million websites, of which around 200 million are active. About 8,000 new websites go live every hour of every day.