Nobel laureate and professor of brain science Eric Kandel describes how our perception of art can help us define a better functional map of the mind.

From the New York Times:

This month, President Obama unveiled a breathtakingly ambitious initiative to map the human brain, the ultimate goal of which is to understand the workings of the human mind in biological terms.

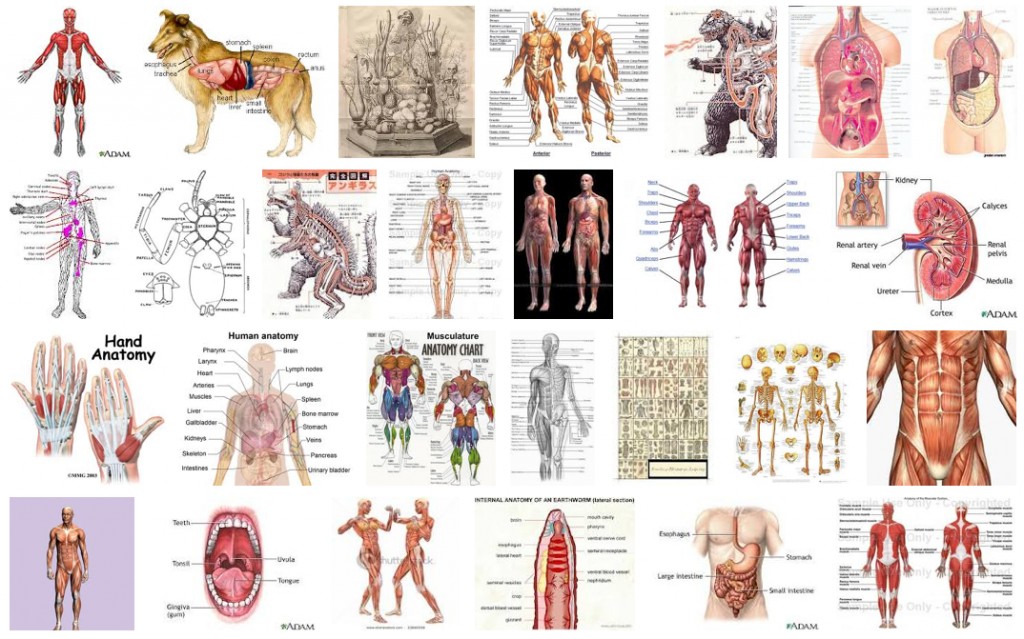

Many of the insights that have brought us to this point arose from the merger over the past 50 years of cognitive psychology, the science of mind, and neuroscience, the science of the brain. The discipline that has emerged now seeks to understand the human mind as a set of functions carried out by the brain.

This new approach to the science of mind not only promises to offer a deeper understanding of what makes us who we are, but also opens dialogues with other areas of study — conversations that may help make science part of our common cultural experience.

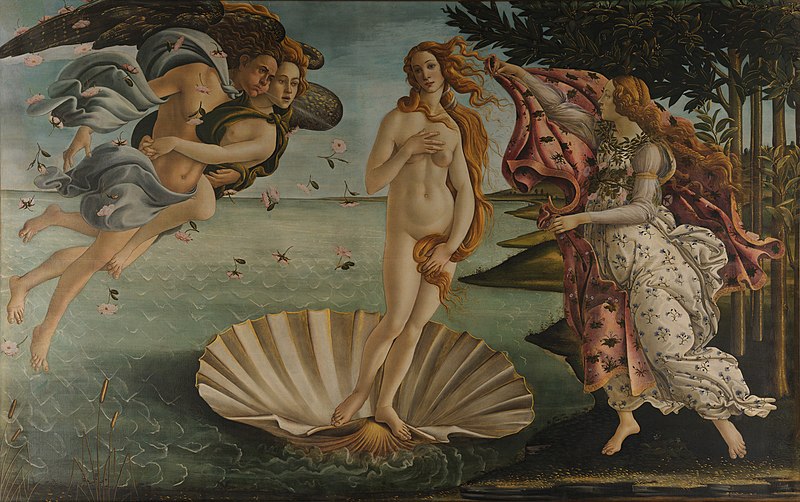

Consider what we can learn about the mind by examining how we view figurative art. In a recently published book, I tried to explore this question by focusing on portraiture, because we are now beginning to understand how our brains respond to the facial expressions and bodily postures of others.

The portraiture that flourished in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century is a good place to start. Not only does this modernist school hold a prominent place in the history of art, it consists of just three major artists — Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele — which makes it easier to study in depth.

As a group, these artists sought to depict the unconscious, instinctual strivings of the people in their portraits, but each painter developed a distinctive way of using facial expressions and hand and body gestures to communicate those mental processes.

Their efforts to get at the truth beneath the appearance of an individual both paralleled and were influenced by similar efforts at the time in the fields of biology and psychoanalysis. Thus the portraits of the modernists in the period known as “Vienna 1900” offer a great example of how artistic, psychological and scientific insights can enrich one another.

The idea that truth lies beneath the surface derives from Carl von Rokitansky, a gifted pathologist who was dean of the Vienna School of Medicine in the middle of the 19th century. Baron von Rokitansky compared what his clinician colleague Josef Skoda heard and saw at the bedsides of his patients with autopsy findings after their deaths. This systematic correlation of clinical and pathological findings taught them that only by going deep below the skin could they understand the nature of illness.

This same notion — that truth is hidden below the surface — was soon steeped in the thinking of Sigmund Freud, who trained at the Vienna School of Medicine in the Rokitansky era and who used psychoanalysis to delve beneath the conscious minds of his patients and reveal their inner feelings. That, too, is what the Austrian modernist painters did in their portraits.

Klimt’s drawings display a nuanced intuition of female sexuality and convey his understanding of sexuality’s link with aggression, picking up on things that even Freud missed. Kokoschka and Schiele grasped the idea that insight into another begins with understanding of oneself. In honest self-portraits with his lover Alma Mahler, Kokoschka captured himself as hopelessly anxious, certain that he would be rejected — which he was. Schiele, the youngest of the group, revealed his vulnerability more deeply, rendering himself, often nude and exposed, as subject to the existential crises of modern life.

Such real-world collisions of artistic, medical and biological modes of thought raise the question: How can art and science be brought together?

Alois Riegl, of the Vienna School of Art History in 1900, was the first to truly address this question. He understood that art is incomplete without the perceptual and emotional involvement of the viewer. Not only does the viewer collaborate with the artist in transforming a two-dimensional likeness on a canvas into a three-dimensional depiction of the world, the viewer interprets what he or she sees on the canvas in personal terms, thereby adding meaning to the picture. Riegl called this phenomenon the “beholder’s involvement” or the “beholder’s share.”

Art history was now aligned with psychology. Ernst Kris and Ernst Gombrich, two of Riegl’s disciples, argued that a work of art is inherently ambiguous and therefore that each person who sees it has a different interpretation. In essence, the beholder recapitulates in his or her own brain the artist’s creative steps.

This insight implied that the brain is a creativity machine, which obtains incomplete information from the outside world and completes it. We can see this with illusions and ambiguous figures that trick our brain into thinking that we see things that are not there. In this sense, a task of figurative painting is to convince the beholder that an illusion is true.

Some of this creative process is determined by the way the structure of our brain develops, which is why we all see the world in pretty much the same way. However, our brains also have differences that are determined in part by our individual experiences.

Read the entire article following the jump.

Only yesterday we

Only yesterday we

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well?

Digital cameras and smartphones have enabled their users to become photographers. Affordable composition and editing tools have made us all designers and editors. Social media have enabled, encouraged and sometimes rewarded us for posting content, reviews and opinions for everything under the sun. So, now we are all critics. So, now are we all curators as well? As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”. [div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]