Feats of memory have long been the staple of human endeavor — for instance, memorizing and recalling Pi to hundreds of decimal places. Nowadays, however, memorization is a competitive sport replete with grand prizes, worthy of a place in an X-Games tournament.

From the NYT:

The last match of the tournament had all the elements of a classic showdown, pitting style versus stealth, quickness versus deliberation, and the world’s foremost card virtuoso against its premier numbers wizard.

If not quite Ali-Frazier or Williams-Sharapova, the duel was all the audience of about 100 could ask for. They had come to the first Extreme Memory Tournament, or XMT, to see a fast-paced, digitally enhanced memory contest, and that’s what they got.

The contest, an unusual collaboration between industry and academic scientists, featured one-minute matches between 16 world-class “memory athletes” from all over the world as they met in a World Cup-like elimination format. The grand prize was $20,000; the potential scientific payoff was large, too.

One of the tournament’s sponsors, the company Dart NeuroScience, is working to develop drugs for improved cognition. The other, Washington University in St. Louis, sent a research team with a battery of cognitive tests to determine what, if anything, sets memory athletes apart. Previous research was sparse and inconclusive.

Yet as the two finalists, both Germans, prepared to face off — Simon Reinhard, 35, a lawyer who holds the world record in card memorization (a deck in 21.19 seconds), and Johannes Mallow, 32, a teacher with the record for memorizing digits (501 in five minutes) — the Washington group had one preliminary finding that wasn’t obvious.

“We found that one of the biggest differences between memory athletes and the rest of us,” said Henry L. Roediger III, the psychologist who led the research team, “is in a cognitive ability that’s not a direct measure of memory at all but of attention.”

The Memory Palace

The technique the competitors use is no mystery.

People have been performing feats of memory for ages, scrolling out pi to hundreds of digits, or phenomenally long verses, or word pairs. Most store the studied material in a so-called memory palace, associating the numbers, words or cards with specific images they have already memorized; then they mentally place the associated pairs in a familiar location, like the rooms of a childhood home or the stops on a subway line.

The Greek poet Simonides of Ceos is credited with first describing the method, in the fifth century B.C., and it has been vividly described in popular books, most recently “Moonwalking With Einstein,” by Joshua Foer.

Each competitor has his or her own variation. “When I see the eight of diamonds and the queen of spades, I picture a toilet, and my friend Guy Plowman,” said Ben Pridmore, 37, an accountant in Derby, England, and a former champion. “Then I put those pictures on High Street in Cambridge, which is a street I know very well.”

As these images accumulate during memorization, they tell an increasingly bizarre but memorable story. “I often use movie scenes as locations,” said James Paterson, 32, a high school psychology teacher in Ascot, near London, who competes in world events. “In the movie ‘Gladiator,’ which I use, there’s a scene where Russell Crowe is in a field, passing soldiers, inspecting weapons.”

Mr. Paterson uses superheroes to represent combinations of letters or numbers: “I might have Batman — one of my images — playing Russell Crowe, and something else playing the horse, and so on.”

The material that competitors attempt to memorize falls into several standard categories. Shuffled decks of cards. Random words. Names matched with faces. And numbers, either binary (ones and zeros) or integers. They are given a set amount of time to study — up to one minute in this tournament, an hour or more in others — before trying to reproduce as many cards, words or digits in the order presented.

Now and then, a challenger boasts online of having discovered an entirely new method, and shows up at competitions to demonstrate it.

“Those people are easy to find, because they come in last, or close to it,” said another world-class competitor, Boris Konrad, 29, a German postdoctoral student in neuroscience. “Everyone here uses this same type of technique.”

Anyone can learn to construct a memory palace, researchers say, and with practice remember far more detail of a particular subject than before. The technique is accessible enough that preteens pick it up quickly, and Mr. Paterson has integrated it into his teaching.

“I’ve got one boy, for instance, he has no interest in academics really, but he knows the Premier League, every team, every player,” he said. “I’m working with him, and he’s using that knowledge as scaffolding to help remember what he’s learning in class.”

Experts in Forgetting

The competitors gathered here for the XMT are not just anyone, however. This is the all-world team, an elite club of laser-smart types who take a nerdy interest in stockpiling facts and pushing themselves hard.

In his doctoral study of 30 world-class performers (most from Germany, which has by far the highest concentration because there are more competitions), Mr. Konrad has found as much. The average I.Q.: 130. Average study time: 1,000 to 2,000 hours and counting. The top competitors all use some variation of the memory-palace system and test, retest and tweak it.

“I started with my own system, but now I use his,” said Annalena Fischer, 20, pointing to her boyfriend, Christian Schäfer, 22, whom she met at a 2010 memory competition in Germany. “Except I don’t use the distance runners he uses; I don’t know anything about the distance runners.” Both are advanced science students and participants in Mr. Konrad’s study.

One of the Washington University findings is predictable, if still preliminary: Memory athletes score very highly on tests of working memory, the mental sketchpad that serves as a shopping list of information we can hold in mind despite distractions.

One way to measure working memory is to have subjects solve a list of equations (5 + 4 = x; 8 + 9 = y; 7 + 2 = z; and so on) while keeping the middle numbers in mind (4, 9 and 2 in the above example). Elite memory athletes can usually store seven items, the top score on the test the researchers used; the average for college students is around two.

“And college students tend to be good at this task,” said Dr. Roediger, a co-author of the new book “Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning.” “What I’d like to do is extend the scoring up to, say, 21, just to see how far the memory athletes can go.”

Yet this finding raises another question: Why don’t the competitors’ memory palaces ever fill up? Players usually have many favored locations to store studied facts, but they practice and compete repeatedly. They use and reuse the same blueprints hundreds of times, and the new images seem to overwrite the old ones — virtually without error.

“Once you’ve remembered the words or cards or whatever it is, and reported them, they’re just gone,” Mr. Paterson said.

Many competitors say the same: Once any given competition is over, the numbers or words or facts are gone. But this is one area in which they have less than precise insight.

In its testing, which began last year, the Washington University team has given memory athletes surprise tests on “old” material — lists of words they’d been tested on the day before. On Day 2, they recalled an average of about three-quarters of the words they memorized on Day 1 (college students remembered fewer than 5 percent). That is, despite what competitors say, the material is not gone; far from it.

Yet to install a fresh image-laden “story” in any given memory palace, a memory athlete must clear away the old one in its entirety. The same process occurs when we change a password: The old one must be suppressed, so it doesn’t interfere with the new one.

One term for that skill is “attentional control,” and psychologists have been measuring it for years with standardized tests. In the best known, the Stroop test, people see words flash by on a computer screen and name the color in which a word is presented. Answering is nearly instantaneous when the color and the word match — “red” displayed in red — but slower when there’s a mismatch, like “red” displayed in blue.

Read the entire article here.

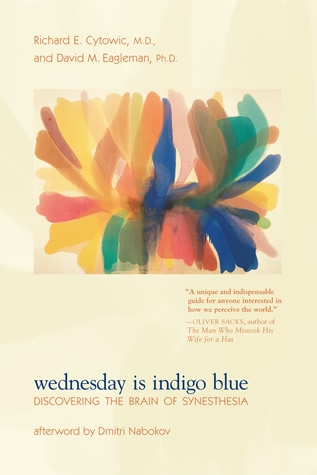

Jonathan Jackson has a very rare form of a rare neurological condition. He has

Jonathan Jackson has a very rare form of a rare neurological condition. He has

A team of psychologists recently compiled and assessed the last words of prison inmates who were facing execution in Texas.

A team of psychologists recently compiled and assessed the last words of prison inmates who were facing execution in Texas. Ever had that curious tingling sensation at the back and base of your neck? Of course you have. Perhaps you’ve felt this sensation during a particular piece of music or from a watching a key scene in a movie or when taking in a panorama from the top of a mountain or from smelling a childhood aroma again. In fact, most people report having felt this sensation, albeit rather infrequently.

Ever had that curious tingling sensation at the back and base of your neck? Of course you have. Perhaps you’ve felt this sensation during a particular piece of music or from a watching a key scene in a movie or when taking in a panorama from the top of a mountain or from smelling a childhood aroma again. In fact, most people report having felt this sensation, albeit rather infrequently.