Ronald Searle, your serious wit and your heroic pen will be missed. Searle died on December 30, aged 91.

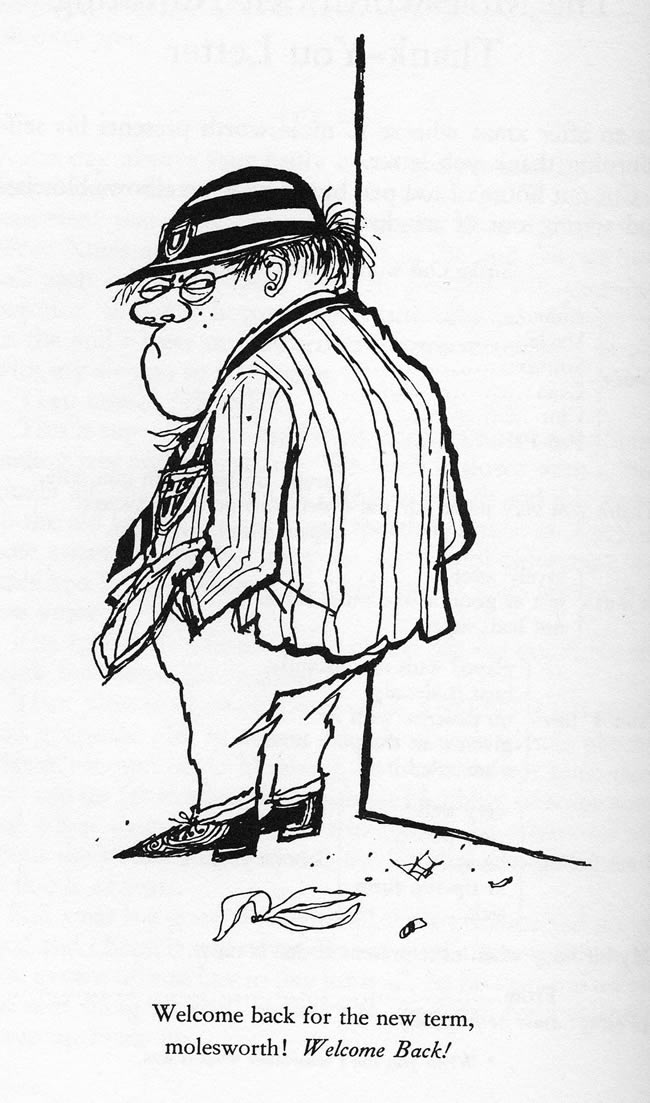

The first “real” book purchased by theDiagonal’s editor with his own money was “How To Be Topp” by Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle. The book featured Searle’s unique and unmistakable illustrations of anti-hero Nigel Molesworth, a stoic, shrewd and droll English schoolboy.

The first “real” book purchased by theDiagonal’s editor with his own money was “How To Be Topp” by Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle. The book featured Searle’s unique and unmistakable illustrations of anti-hero Nigel Molesworth, a stoic, shrewd and droll English schoolboy.

Yet while Searle will be best remembered for his drawings of Molesworth and friends at St.Custard’s high school and his invention of St.Trinian’s (school for rowdy schoolgirls), he leaves behind a critical body of work that graphically illustrates his brutal captivity at the hands of the Japanese during the Second World War.

Most of these drawings appear in his 1986 book, Ronald Searle: To the Kwai and Back, War Drawings 1939-1945. In the book, Searle also wrote of his experiences as a prisoner. Many of his original drawings are now in the permanent collection of the Imperial War Museum, London.

[div class=attrib]From the BBC:[end-div]

British cartoonist Ronald Searle, best known for creating the fictional girls’ school St Trinian’s, has died aged 91.

His daughter Kate Searle said in a statement that he “passed away peacefully in his sleep” in a hospital in France.

Searle’s spindly cartoons of the naughty schoolgirls first appeared in 1941, before the idea was adapted for film.

The first movie version, The Belles of St Trinian’s, was released in 1954.

Joyce Grenfell and George Cole starred in the film, along with Alastair Sim, who appeared in drag as headmistress Millicent Fritton.

Searle also provided illustrations the Molesworth series, written by Geoffrey Willans.

The gothic, line-drawn cartoons breathed life into the gruesome pupils of St Custard’s school, in particular the outspoken, but functionally-illiterate Nigel Molesworth “the goriller of 3B”.

Searle’s work regularly appeared in magazines and newspapers, including Punch and The New Yorker.

[div class=attrib]Read more here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Welcome back to the new term molesworth! From How to be Topp. Courtesy of Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle / Vanguard Press.[end-div]

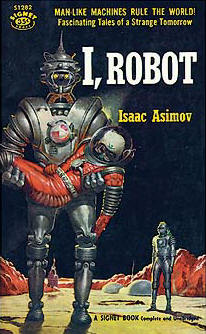

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics:

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics: