We think CDM sounds much more fun than LHC, a rather dry acronym for Large Hadron Collider.

We think CDM sounds much more fun than LHC, a rather dry acronym for Large Hadron Collider.

Researchers at the LHC are set to announce the latest findings in early July from the record-breaking particle smasher buried below the French and Swiss borders. Rumors point towards the discovery of the so-called Higgs boson, the particle theorized to give mass to all the other fundamental building blocks of matter. So, while this would be another exciting discovery from CERN and yet another confirmation of the fundamental and elegant Standard Model of particle physics, perhaps there is yet more to uncover, such as the exotically named “inflaton”.

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

Within a sliver of a second after it was born, our universe expanded staggeringly in size, by a factor of at least 10^26. That’s what most cosmologists maintain, although it remains a mystery as to what might have begun and ended this wild expansion. Now scientists are increasingly wondering if the most powerful particle collider in history, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Europe, could shed light on this mysterious growth, called inflation, by catching a glimpse of the particle behind it. It could be that the main target of the collider’s current experiments, the Higgs boson, which is thought to endow all matter with mass, could also be this inflationary agent.

During inflation, spacetime is thought to have swelled in volume at an accelerating rate, from about a quadrillionth the size of an atom to the size of a dime. This rapid expansion would help explain why the cosmos today is as extraordinarily uniform as it is, with only very tiny variations in the distribution of matter and energy. The expansion would also help explain why the universe on a large scale appears geometrically flat, meaning that the fabric of space is not curved in a way that bends the paths of light beams and objects traveling within it.

The particle or field behind inflation, referred to as the “inflaton,” is thought to possess a very unusual property: it generates a repulsive gravitational field. To cause space to inflate as profoundly and temporarily as it did, the field’s energy throughout space must have varied in strength over time, from very high to very low, with inflation ending once the energy sunk low enough, according to theoretical physicists.

Much remains unknown about inflation, and some prominent critics of the idea wonder if it happened at all. Scientists have looked at the cosmic microwave background radiation—the afterglow of the big bang—to rule out some inflationary scenarios. “But it cannot tell us much about the nature of the inflaton itself,” says particle cosmologist Anupam Mazumdar at Lancaster University in England, such as its mass or the specific ways it might interact with other particles.

A number of research teams have suggested competing ideas about how the LHC might discover the inflaton. Skeptics think it highly unlikely that any earthly particle collider could shed light on inflation, because the uppermost energy densities one could imagine with inflation would be about 10^50 times above the LHC’s capabilities. However, because inflation varied with strength over time, scientists have argued the LHC may have at least enough energy to re-create inflation’s final stages.

It could be that the principal particle ongoing collider runs aim to detect, the Higgs boson, could also underlie inflation.

“The idea of the Higgs driving inflation can only take place if the Higgs’s mass lies within a particular interval, the kind which the LHC can see,” says theoretical physicist Mikhail Shaposhnikov at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland. Indeed, evidence of the Higgs boson was reported at the LHC in December at a mass of about 125 billion electron volts, roughly the mass of 125 hydrogen atoms.

Also intriguing: the Higgs as well as the inflaton are thought to have varied with strength over time. In fact, the inventor of inflation theory, cosmologist Alan Guth at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, originally assumed inflation was driven by the Higgs field of a conjectured grand unified theory.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

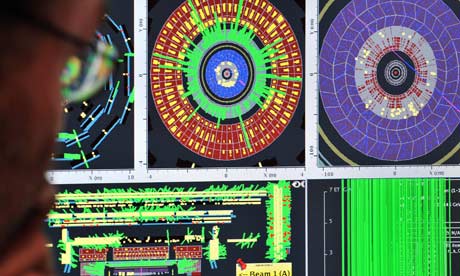

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Physics World.[end-div]

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox. Two exciting races tracked through Grenoble, France this passed week. First, the Tour de France held one of the definitive stages of the 2011 race in Grenoble, the individual time trial. Second, Grenoble hosted the

Two exciting races tracked through Grenoble, France this passed week. First, the Tour de France held one of the definitive stages of the 2011 race in Grenoble, the individual time trial. Second, Grenoble hosted the  Both colliders have been smashing particles together in their ongoing quest to refine our understanding of the building blocks of matter, and to determine the existence of the Higgs particle. The Higgs is believed to convey mass to other particles, and remains one of the remaining undiscovered components of the Standard Model of physics.

Both colliders have been smashing particles together in their ongoing quest to refine our understanding of the building blocks of matter, and to determine the existence of the Higgs particle. The Higgs is believed to convey mass to other particles, and remains one of the remaining undiscovered components of the Standard Model of physics.