Most of us now carry around inside our smartphones more computing power than NASA once had in the Apollo command module. So, it’s interesting to look back at old movies to see how celluloid fiction portrayed computers. Most from the 1950s and 60s were replete with spinning tape drives and enough lights to resemble the Manhattan skyline. Our favorite here at theDiagonal is the first “Bat Computer” from the original 1960’s TV series, which could be found churning away in Batman’s crime-fighting nerve center beneath Wayne Mansion.

[div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div]

The United States government powered up its SAGE defense system in July 1958, at an Air Force base near Trenton, New Jersey. Short for Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, SAGE would eventually span 24 command and control stations across the US and Canada, warning against potential air attacks via radar and an early IBM computer called the AN/FSQ-7.

“It automated air defense,” says Mike Loewen, who worked with SAGE while serving with the Air Force in the 1980s. “It used a versatile, programmable, digital computer to process all this incoming radar data from various sites around the region and display it in a format that made sense to people. It provided a computer display of the digitally processed radar information.”

Fronted by a wall of dials, switches, neon lights, and incandescent lamps — and often plugged into spinning tape drives stretching from floor to ceiling — the AN/FSQ-7 looked like one of those massive computing systems that turned up in Hollywood movies and prime time TV during the ’60s and the ’70s. This is mainly because it is one those massive computing systems that turned up in Hollywood movies and TV during the ’60s and ’70s — over and over and over again. Think Lost In Space. Get Smart. Fantastic Voyage. In Like Flint. Or our person favorite: The Towering Inferno.

That’s the AN/FSQ-7 in The Towering Inferno at the top of this page, operated by a man named OJ Simpson, trying to track a fire that’s threatening to bring down the world’s tallest building.

For decades, the AN/FSQ-7 — Q7 for short — helped define the image of a computer in the popular consciousness. Nevermind that it was just a radar system originally backed by tens of thousands of vacuum tubes. For moviegoers everywhere, this was the sort of thing that automated myriad tasks not only in modern-day America but the distant future.

It never made much sense. But sometimes, it made even less sense. In the ’60s and ’70s, some films didn’t see the future all that clearly. Woody Allen’s Sleeper is set in 2173, and it shows the AN/FSQ-7 helping 22nd-century Teamsters make repairs to robotic man servants. Other films just didn’t see the present all that clearly. Independence Day was made in 1996, and apparently, its producers were unaware that the Air Force decommissioned SAGE 13 years earlier.

Of course, the Q7 is only part of the tale. The history of movies and TV is littered with big, beefy, photogenic machines that make absolutely no sense whatsoever. Sometimes they’re real machines doing unreal tasks. And sometimes they’re unreal machines doing unreal tasks. But we love them all. Oh so very much.

Mike Loewen first noticed the Q7 in a mid-’60s prime time TV series called The Time Tunnel. Produced by the irrepressible Irwin Allen, Time Tunnel concerned a secret government project to build a time machine beneath a trap door in the Arizona desert. A Q7 powered this subterranean time machine, complete with all those dials, switches, neon lights, and incandescent lamps.

No, an AN/FSQ-7 couldn’t really power a time machine. But time machines don’t exist. So it all works out quite nicely.

At first, Loewen didn’t know it was a Q7. But then, after he wound up in front of a SAGE system while in the Air Force many years later, it all came together. “I realized that these computer banks running the Time Tunnel were large sections of panels from the SAGE computer,” Loewen says. “And that’s where I got interested.”

He noticed the Q7 in TV show after TV show, movie after movie — and he started documenting these SAGE star turns on his personal homepage. In each case, the Q7 was seen doing stuff it couldn’t possibly do, but there was no doubt this was the Q7 — or at least part of it.

…

Here’s that subterranean time machine that caught the eye of Mike Loewen in The Time Tunnel (1966). The cool thing about the Time Tunnel AN/FSQ-7 is that even when it traps two government scientists in an endless time warp, it always sends them to dates of extremely important historical significance. Otherwise, you’d have one boring TV show on your hands.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article following the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: The Time Tunnel (1966). Courtesy of Wired.[end-div]

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color. A month in to fall and it really does now seem like Autumn — leaves are turning and falling, jackets have reappeared, brisk morning walks are now shrouded in darkness.

A month in to fall and it really does now seem like Autumn — leaves are turning and falling, jackets have reappeared, brisk morning walks are now shrouded in darkness. Author Joe Queenan explains why reading over 6,000 books may be because, as he puts it, he “find[s] ‘reality’ a bit of a disappointment”.

Author Joe Queenan explains why reading over 6,000 books may be because, as he puts it, he “find[s] ‘reality’ a bit of a disappointment”. QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No.

QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No. Hint. The answer is not shameless self-promotion or exploitative voyeurism; images used in this way may scratch a personal itch, but rarely influence fundamental societal or political behavior. Importantly, photography has given us a rich, nuanced and lasting medium for artistic expression since cameras and film were first invented. However, the principal answer is lies in photography’s ability to tell truth about and to power.

Hint. The answer is not shameless self-promotion or exploitative voyeurism; images used in this way may scratch a personal itch, but rarely influence fundamental societal or political behavior. Importantly, photography has given us a rich, nuanced and lasting medium for artistic expression since cameras and film were first invented. However, the principal answer is lies in photography’s ability to tell truth about and to power.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”. When it comes to music a generational gap has always been with us, separating young from old. Thus, without fail, parents will remark that the music listened to by their kids is loud and monotonous, nothing like the varied and much better music that they consumed in their younger days.

When it comes to music a generational gap has always been with us, separating young from old. Thus, without fail, parents will remark that the music listened to by their kids is loud and monotonous, nothing like the varied and much better music that they consumed in their younger days. Accessorize

Accessorize

Slip

Slip

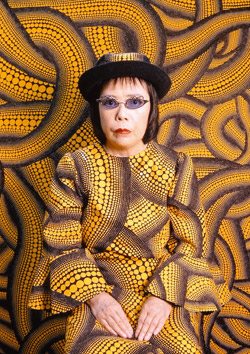

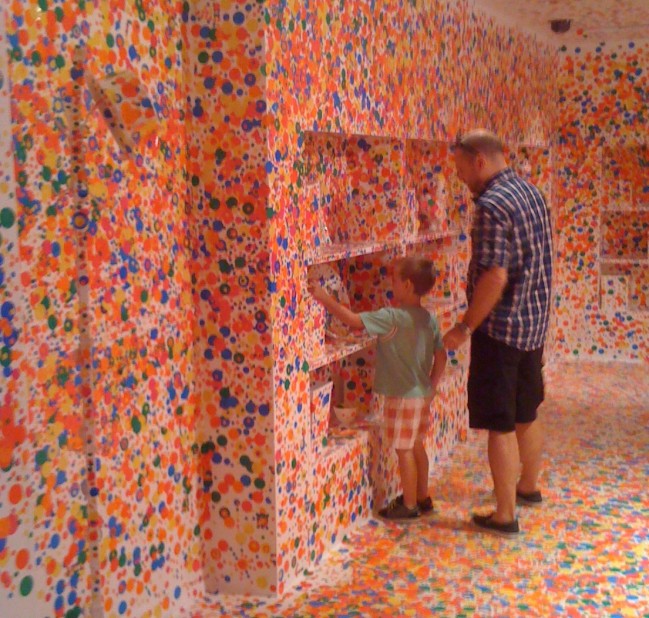

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

The recent finding in a Spanish cave of a painted “red dot” dating from around 40,800 years ago suggests that our Neanderthal cousins may have beaten our species to claim the prize of “first artist”. Yet, evidence remains scant, and even if this were proven to be the case, we Homo sapiens can certainly lay claim to taking it beyond a “red dot” and making art our very own (and much else too.)

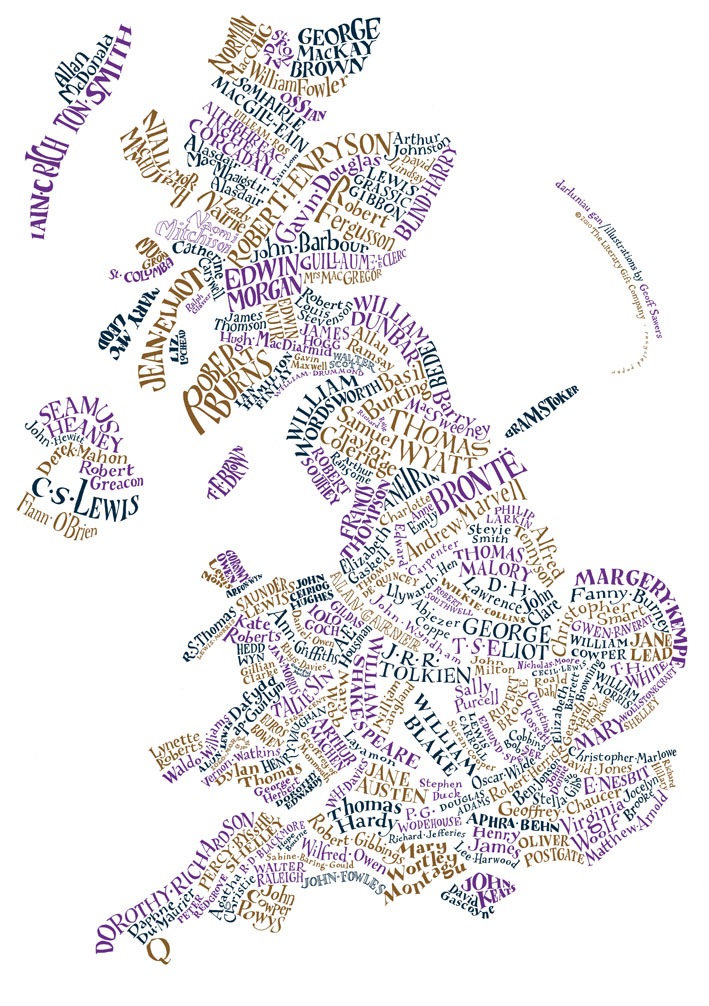

The official start of summer in the northern hemisphere is just over a week away. So, it’s time to gather together some juicy reads for lazy days by the beach or under a sturdy shade tree. Flavorwire offers a classic list of 30 reads with a couple of surprises thrown in. And, we’ll qualify Flavorwire’s selection by adding that anyone over 30 should read these works as well.

The official start of summer in the northern hemisphere is just over a week away. So, it’s time to gather together some juicy reads for lazy days by the beach or under a sturdy shade tree. Flavorwire offers a classic list of 30 reads with a couple of surprises thrown in. And, we’ll qualify Flavorwire’s selection by adding that anyone over 30 should read these works as well.

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

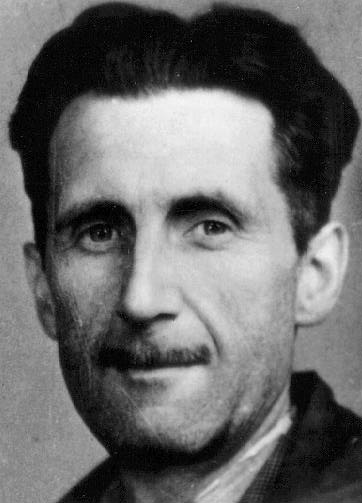

Professor of philosophy Simon Critchley has an insightful examination (serialized) of Philip K. Dick’s writings. Philip K. Dick had a tragically short, but richly creative writing career. Since his death twenty years ago, many of his novels have profoundly influenced contemporary culture.

Professor of philosophy Simon Critchley has an insightful examination (serialized) of Philip K. Dick’s writings. Philip K. Dick had a tragically short, but richly creative writing career. Since his death twenty years ago, many of his novels have profoundly influenced contemporary culture.