A sad story chronicling the rise in amphetamine use in the quest for good school grades. More frightening now is the increase in addiction of ever younger kids, and not for dubious goal of excelling at school. Many kids are just taking the drug to get high.

[div class=attrib]From the Telegraph:[end-div]

The New York Times has finally woken up to America’s biggest unacknowledged drug problem: the massive overprescription of the amphetamine drug Adderall for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Kids have been selling each other this powerful – and extremely moreish – mood enhancer for years, as ADHD diagnoses and prescriptions for the drug have shot up.

Now, children are snorting the stuff, breaking open the capsules and ingesting it using the time-honoured tool of a rolled-up bank note.

The NYT seems to think these teenage drug users are interested in boosting their grades. It claims that, for children without ADHD, “just one pill can jolt them with the energy focus to push through all-night homework binges and stay awake during exams afterward”.

Really? There are two problems with this.

First, the idea that ADHD kids are “normal” on Adderall and its methylphenidate alternative Ritalin – gentler in its effect but still a psychostimulant – is open to question. Reading this scorching article by the child psychologist Prof L Alan Sroufe, who says there’s no evidence that attention-deficit children are born with an organic disease, or that ADHD and non-ADHD kids react differently to their doctor-prescribed amphetamines. Yes, there’s an initial boost to concentration, but the effect wears off – and addiction often takes its place.

Second, the school pupils illicitly borrowing or buying Adderall aren’t necessarily doing it to concentrate on their work. They’re doing it to get high.

Adderall, with its mixture of amphetamine salts, has the ability to make you as euphoric as a line of cocaine – and keep you that way, particularly if it’s the slow-release version and you’re taking it for the first time. At least, that was my experience. Here’s what happened.

I was staying with a hospital consultant and his attorney wife in the East Bay just outside San Francisco. I’d driven overnight from Los Angeles after a flight from London; I was jetlagged, sleep-deprived and facing a deadline to write an article for the Spectator about, of all things, Bach cantatas.

Sitting in the courtyard garden with my laptop, I tapped and deleted one clumsy sentence after another. The sun was going down; my hostess saw me shivering and popped out with a blanket, a cup of herbal tea and ‘something to help you concentrate’.

I took the pill, didn’t notice any effect, and was glad when I was called in for dinner.

The dining room was a Californian take on the Second Empire. The lady next to me was a Southern Belle turned realtor, her eyelids already drooping from the effects of her third giant glass of Napa Valley chardonnay. She began to tell me about her divorce. Every time she refilled her glass, her new husband raised his eyes to heaven.

It felt as if I was stuck in an episode of Dallas, or a very bad Tennessee Williams play. But it didn’t matter in the least because, at some stage between the mozzarella salad and the grilled chicken, I’d become as high as a kite.

Adderall helps you concentrate, no doubt about it. I was riveted by the details of this woman’s alimony settlement. Even she, utterly self- obsessed as she was, was surprised by my gushing empathy. After dinner, I sat down at the kitchen table to finish the article. The head rush was beginning to wear off, but then, just as I started typing, a second wave of amphetamine pushed its way into my bloodstream. This was timed-release Adderall. Gratefully I plunged into 18th-century Leipzig, meticulously noting the catalogue numbers of cantatas. It was as if the great Johann Sebastian himself was looking over my shoulder. By the time I glanced at the clock, it was five in the morning. My pleasure at finishing the article was boosted by the dopamine high. What a lovely drug.

The blues didn’t hit me until the next day – and took the best part of a week to banish.

And this is what they give to nine-year-olds.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

He steered into the high school parking lot, clicked off the ignition and scanned the scraps of his recent weeks. Crinkled chip bags on the dashboard. Soda cups at his feet. And on the passenger seat, a rumpled SAT practice book whose owner had been told since fourth grade he was headed to the Ivy League. Pencils up in 20 minutes.

The boy exhaled. Before opening the car door, he recalled recently, he twisted open a capsule of orange powder and arranged it in a neat line on the armrest. He leaned over, closed one nostril and snorted it.

Throughout the parking lot, he said, eight of his friends did the same thing.

The drug was not cocaine or heroin, but Adderall, an amphetamine prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder that the boy said he and his friends routinely shared to study late into the night, focus during tests and ultimately get the grades worthy of their prestigious high school in an affluent suburb of New York City. The drug did more than just jolt them awake for the 8 a.m. SAT; it gave them a tunnel focus tailor-made for the marathon of tests long known to make or break college applications.

“Everyone in school either has a prescription or has a friend who does,” the boy said.

At high schools across the United States, pressure over grades and competition for college admissions are encouraging students to abuse prescription stimulants, according to interviews with students, parents and doctors. Pills that have been a staple in some college and graduate school circles are going from rare to routine in many academically competitive high schools, where teenagers say they get them from friends, buy them from student dealers or fake symptoms to their parents and doctors to get prescriptions.

Of the more than 200 students, school officials, parents and others contacted for this article, about 40 agreed to share their experiences. Most students spoke on the condition that they be identified by only a first or middle name, or not at all, out of concern for their college prospects or their school systems’ reputations — and their own.

“It’s throughout all the private schools here,” said DeAnsin Parker, a New York psychologist who treats many adolescents from affluent neighborhoods like the Upper East Side. “It’s not as if there is one school where this is the culture. This is the culture.”

Observed Gary Boggs, a special agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration, “We’re seeing it all across the United States.”

The D.E.A. lists prescription stimulants like Adderall and Vyvanse (amphetamines) and Ritalin and Focalin (methylphenidates) as Class 2 controlled substances — the same as cocaine and morphine — because they rank among the most addictive substances that have a medical use. (By comparison, the long-abused anti-anxiety drug Valium is in the lower Class 4.) So they carry high legal risks, too, as few teenagers appreciate that merely giving a friend an Adderall or Vyvanse pill is the same as selling it and can be prosecuted as a felony.

While these medicines tend to calm people with A.D.H.D., those without the disorder find that just one pill can jolt them with the energy and focus to push through all-night homework binges and stay awake during exams afterward. “It’s like it does your work for you,” said William, a recent graduate of the Birch Wathen Lenox School on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

But abuse of prescription stimulants can lead to depression and mood swings (from sleep deprivation), heart irregularities and acute exhaustion or psychosis during withdrawal, doctors say. Little is known about the long-term effects of abuse of stimulants among the young. Drug counselors say that for some teenagers, the pills eventually become an entry to the abuse of painkillers and sleep aids.

“Once you break the seal on using pills, or any of that stuff, it’s not scary anymore — especially when you’re getting A’s,” said the boy who snorted Adderall in the parking lot. He spoke from the couch of his drug counselor, detailing how he later became addicted to the painkiller Percocet and eventually heroin.

Paul L. Hokemeyer, a family therapist at Caron Treatment Centers in Manhattan, said: “Children have prefrontal cortexes that are not fully developed, and we’re changing the chemistry of the brain. That’s what these drugs do. It’s one thing if you have a real deficiency — the medicine is really important to those people — but not if your deficiency is not getting into Brown.”

The number of prescriptions for A.D.H.D. medications dispensed for young people ages 10 to 19 has risen 26 percent since 2007, to almost 21 million yearly, according to IMS Health, a health care information company — a number that experts estimate corresponds to more than two million individuals. But there is no reliable research on how many high school students take stimulants as a study aid. Doctors and teenagers from more than 15 schools across the nation with high academic standards estimated that the portion of students who do so ranges from 15 percent to 40 percent.

“They’re the A students, sometimes the B students, who are trying to get good grades,” said one senior at Lower Merion High School in Ardmore, a Philadelphia suburb, who said he makes hundreds of dollars a week selling prescription drugs, usually priced at $5 to $20 per pill, to classmates as young as freshmen. “They’re the quote-unquote good kids, basically.”

The trend was driven home last month to Nan Radulovic, a psychotherapist in Santa Monica, Calif. Within a few days, she said, an 11th grader, a ninth grader and an eighth grader asked for prescriptions for Adderall solely for better grades. From one girl, she recalled, it was not quite a request.

“If you don’t give me the prescription,” Dr. Radulovic said the girl told her, “I’ll just get it from kids at school.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Illegal use of Adderall is prevalent enough that many students seem to take it for granted. Courtesy of Minnesota Post / Flickr/ CC/ Hipsxxhearts.[end-div]

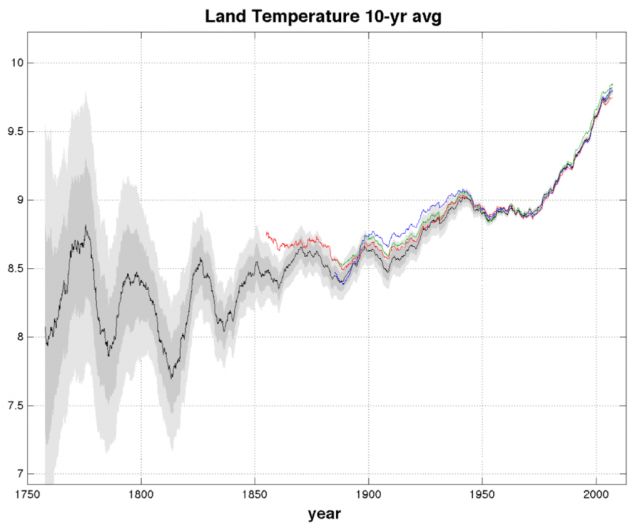

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

It takes no expert neuroscientist, anthropologist or evolutionary biologist to recognize that human evolution has probably stalled. After all, one only needs to observe our obsession with reality TV. Yes, evolution screeched to a halt around 1999, when reality TV hit critical mass in the mainstream public consciousness. So, what of evolution?

It takes no expert neuroscientist, anthropologist or evolutionary biologist to recognize that human evolution has probably stalled. After all, one only needs to observe our obsession with reality TV. Yes, evolution screeched to a halt around 1999, when reality TV hit critical mass in the mainstream public consciousness. So, what of evolution? Christopher Mims over at the Technology Review revisits a recent study of our social networks, both real-world and online. It’s startling to see the growth in our social isolation despite the corresponding growth in technologies that increase our ability to communicate and interact with one another. Is the suburbanization of our species to blame, and can Facebook save us?

Christopher Mims over at the Technology Review revisits a recent study of our social networks, both real-world and online. It’s startling to see the growth in our social isolation despite the corresponding growth in technologies that increase our ability to communicate and interact with one another. Is the suburbanization of our species to blame, and can Facebook save us?

Why can’t our kids tie their own shoes?

Why can’t our kids tie their own shoes?

[div class=attrib]From Cosmic Log:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Cosmic Log:[end-div]

Jane Brody over at the Well blog makes a compelling case for the dismantling of suburbia. After all, these so-called “built environments” where we live, work, eat, play and raise our children, are an increasingly serious health hazard.

Jane Brody over at the Well blog makes a compelling case for the dismantling of suburbia. After all, these so-called “built environments” where we live, work, eat, play and raise our children, are an increasingly serious health hazard.

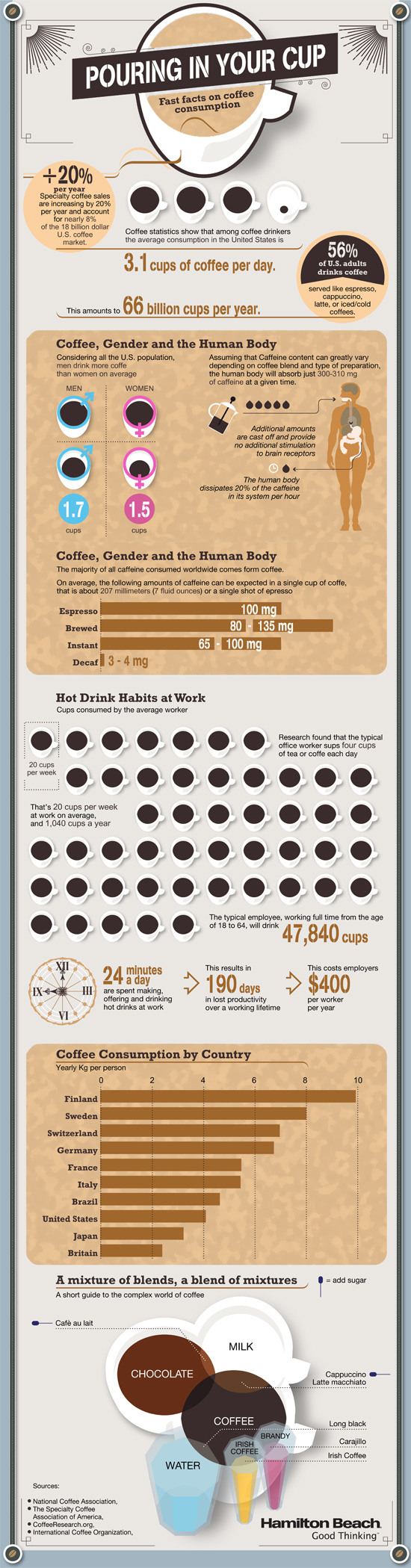

Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource.

Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource.