A sad symptom of our expanding media binge culture and the fragmentation of our shortening attention spans is the demise of literary fiction. Author Will Self believes the novel, and narrative prose in general, is on a slow, but accelerating, death-spiral. His eloquent views presented in a May 6, 2014 lecture are excerpted below.

A sad symptom of our expanding media binge culture and the fragmentation of our shortening attention spans is the demise of literary fiction. Author Will Self believes the novel, and narrative prose in general, is on a slow, but accelerating, death-spiral. His eloquent views presented in a May 6, 2014 lecture are excerpted below.

From the Guardian:

If you happen to be a writer, one of the great benisons of having children is that your personal culture-mine is equipped with its own canaries. As you tunnel on relentlessly into the future, these little harbingers either choke on the noxious gases released by the extraction of decadence, or they thrive in the clean air of what we might call progress. A few months ago, one of my canaries, who’s in his mid-teens and harbours a laudable ambition to be the world’s greatest ever rock musician, was messing about on his electric guitar. Breaking off from a particularly jagged and angry riff, he launched into an equally jagged diatribe, the gist of which was already familiar to me: everything in popular music had been done before, and usually those who’d done it first had done it best. Besides, the instant availability of almost everything that had ever been done stifled his creativity, and made him feel it was all hopeless.

A miner, if he has any sense, treats his canary well, so I began gently remonstrating with him. Yes, I said, it’s true that the web and the internet have created a permanent Now, eliminating our sense of musical eras; it’s also the case that the queered demographics of our longer-living, lower-birthing population means that the middle-aged squat on top of the pyramid of endeavour, crushing the young with our nostalgic tastes. What’s more, the decimation of the revenue streams once generated by analogues of recorded music have put paid to many a musician’s income. But my canary had to appreciate this: if you took the long view, the advent of the 78rpm shellac disc had also been a disaster for musicians who in the teens and 20s of the last century made their daily bread by live performance. I repeated one of my favourite anecdotes: when the first wax cylinder recording of Feodor Chaliapin singing “The Song of the Volga Boatmen“ was played, its listeners, despite a lowness of fidelity that would seem laughable to us (imagine a man holding forth from a giant bowl of snapping, crackling and popping Rice Krispies), were nonetheless convinced the portly Russian must be in the room, and searched behind drapes and underneath chaise longues for him.

So recorded sound blew away the nimbus of authenticity surrounding live performers – but it did worse things. My canaries have often heard me tell how back in the 1970s heyday of the pop charts, all you needed was a writing credit on some loathsome chirpy-chirpy-cheep-cheeping ditty in order to spend the rest of your born days lying by a guitar-shaped pool in the Hollywood Hills hoovering up cocaine. Surely if there’s one thing we have to be grateful for it’s that the web has put paid to such an egregious financial multiplier being applied to raw talentlessness. Put paid to it, and also returned musicians to the domain of live performance and, arguably, reinvigorated musicianship in the process. Anyway, I was saying all of this to my canary when I was suddenly overtaken by a great wave of noxiousness only I could smell. I faltered, I fell silent, then I said: sod you and your creative anxieties, what about me? How do you think it feels to have dedicated your entire adult life to an art form only to see the bloody thing dying before your eyes?

My canary is a perceptive songbird – he immediately ceased his own cheeping, except to chirrup: I see what you mean. The literary novel as an art work and a narrative art form central to our culture is indeed dying before our eyes. Let me refine my terms: I do not mean narrative prose fiction tout court is dying – the kidult boywizardsroman and the soft sadomasochistic porn fantasy are clearly in rude good health. And nor do I mean that serious novels will either cease to be written or read. But what is already no longer the case is the situation that obtained when I was a young man. In the early 1980s, and I would argue throughout the second half of the last century, the literary novel was perceived to be the prince of art forms, the cultural capstone and the apogee of creative endeavour. The capability words have when arranged sequentially to both mimic the free flow of human thought and investigate the physical expressions and interactions of thinking subjects; the way they may be shaped into a believable simulacrum of either the commonsensical world, or any number of invented ones; and the capability of the extended prose form itself, which, unlike any other art form, is able to enact self-analysis, to describe other aesthetic modes and even mimic them. All this led to a general acknowledgment: the novel was the true Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk.

This is not to say that everyone walked the streets with their head buried in Ulysses or To the Lighthouse, or that popular culture in all its forms didn’t hold sway over the psyches and imaginations of the great majority. Nor do I mean to suggest that in our culture perennial John Bull-headed philistinism wasn’t alive and snorting: “I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.” However, what didn’t obtain is the current dispensation, wherein those who reject the high arts feel not merely entitled to their opinion, but wholly justified in it. It goes further: the hallmark of our contemporary culture is an active resistance to difficulty in all its aesthetic manifestations, accompanied by a sense of grievance that conflates it with political elitism. Indeed, it’s arguable that tilting at this papery windmill of artistic superiority actively prevents a great many people from confronting the very real economic inequality and political disenfranchisement they’re subject to, exactly as being compelled to chant the mantra “choice” drowns out the harsh background Muzak telling them they have none.

Just because you’re paranoid it doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you. Simply because you’ve remarked a number of times on the concealed fox gnawing its way into your vitals, it doesn’t mean it hasn’t at this moment swallowed your gall bladder. Ours is an age in which omnipresent threats of imminent extinction are also part of the background noise – nuclear annihilation, terrorism, climate change. So we can be blinkered when it comes to tectonic cultural shifts. The omnipresent and deadly threat to the novel has been imminent now for a long time – getting on, I would say, for a century – and so it’s become part of culture. During that century, more books of all kinds have been printed and read by far than in the entire preceding half millennium since the invention of movable-type printing. If this was death it had a weird, pullulating way of expressing itself. The saying is that there are no second acts in American lives; the novel, I think, has led a very American sort of life: swaggering, confident, brash even – and ever aware of its world-conquering manifest destiny. But unlike Ernest Hemingway or F Scott Fitzgerald, the novel has also had a second life. The form should have been laid to rest at about the time of Finnegans Wake, but in fact it has continued to stalk the corridors of our minds for a further three-quarters of a century. Many fine novels have been written during this period, but I would contend that these were, taking the long view, zombie novels, instances of an undead art form that yet wouldn’t lie down.

Literary critics – themselves a dying breed, a cause for considerable schadenfreude on the part of novelists – make all sorts of mistakes, but some of the most egregious ones result from an inability to think outside of the papery prison within which they conduct their lives’ work. They consider the codex. They are – in Marshall McLuhan’s memorable phrase – the possessors of Gutenberg minds.

There is now an almost ceaseless murmuring about the future of narrative prose. Most of it is at once Panglossian and melioristic: yes, experts assert, there’s no disputing the impact of digitised text on the whole culture of the codex; fewer paper books are being sold, newspapers fold, bookshops continue to close, libraries as well. But … but, well, there’s still no substitute for the experience of close reading as we’ve come to understand and appreciate it – the capacity to imagine entire worlds from parsing a few lines of text; the ability to achieve deep and meditative levels of absorption in others’ psyches. This circling of the wagons comes with a number of public-spirited campaigns: children are given free books; book bags are distributed with slogans on them urging readers to put books in them; books are hymned for their physical attributes – their heft, their appearance, their smell – as if they were the bodily correlates of all those Gutenberg minds, which, of course, they are.

The seeming realists among the Gutenbergers say such things as: well, clearly, books are going to become a minority technology, but the beau livre will survive. The populist Gutenbergers prate on about how digital texts linked to social media will allow readers to take part in a public conversation. What none of the Gutenbergers are able to countenance, because it is quite literally – for once the intensifier is justified – out of their minds, is that the advent of digital media is not simply destructive of the codex, but of the Gutenberg mind itself. There is one question alone that you must ask yourself in order to establish whether the serious novel will still retain cultural primacy and centrality in another 20 years. This is the question: if you accept that by then the vast majority of text will be read in digital form on devices linked to the web, do you also believe that those readers will voluntarily choose to disable that connectivity? If your answer to this is no, then the death of the novel is sealed out of your own mouth.

Read the entire excerpt here.

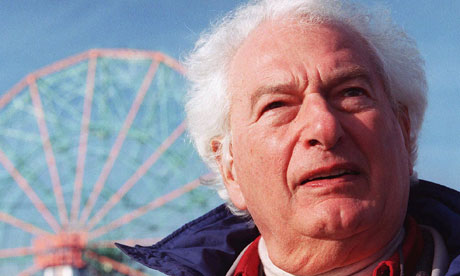

Image: Will Self, 2007. Courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.

Iain (M.) Banks is now where he rightfully belongs — hurtling through space. Though, we fear that he may well not be traveling as fast as he would have wished.

Iain (M.) Banks is now where he rightfully belongs — hurtling through space. Though, we fear that he may well not be traveling as fast as he would have wished. Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

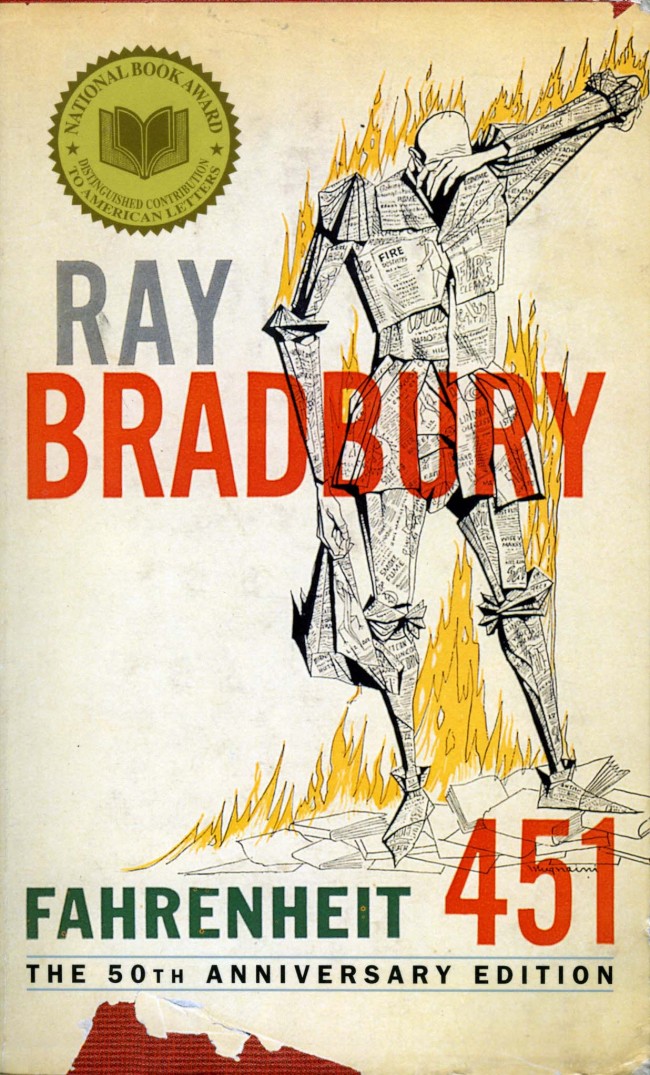

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451]. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]