[div class=attrib]From Eurozine:[end-div]

“There is only one way to turn signals into information, through interpretation”, wrote the computer critic Joseph Weizenbaum. As Google’s hegemony over online content increases, argues Geert Lovink, we should stop searching and start questioning.

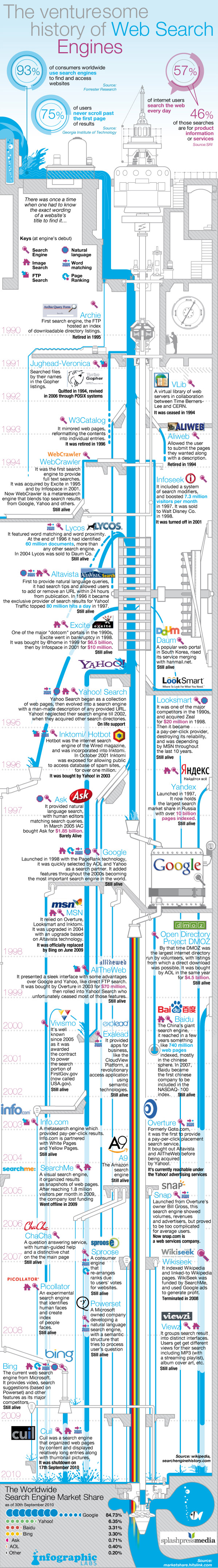

A spectre haunts the world’s intellectual elites: information overload. Ordinary people have hijacked strategic resources and are clogging up once carefully policed media channels. Before the Internet, the mandarin classes rested on the idea that they could separate “idle talk” from “knowledge”. With the rise of Internet search engines it is no longer possible to distinguish between patrician insights and plebeian gossip. The distinction between high and low, and their co-mingling on occasions of carnival, belong to a bygone era and should no longer concern us. Nowadays an altogether new phenomenon is causing alarm: search engines rank according to popularity, not truth. Search is the way we now live. With the dramatic increase of accessed information, we have become hooked on retrieval tools. We look for telephone numbers, addresses, opening times, a person’s name, flight details, best deals and in a frantic mood declare the ever growing pile of grey matter “data trash”. Soon we will search and only get lost. Old hierarchies of communication have not only imploded, communication itself has assumed the status of cerebral assault. Not only has popular noise risen to unbearable levels, we can no longer stand yet another request from colleagues and even a benign greeting from friends and family has acquired the status of a chore with the expectation of reply. The educated class deplores that fact that chatter has entered the hitherto protected domain of science and philosophy, when instead they should be worrying about who is going to control the increasingly centralized computing grid.

What today’s administrators of noble simplicity and quiet grandeur cannot express, we should say for them: there is a growing discontent with Google and the way the Internet organizes information retrieval. The scientific establishment has lost control over one of its key research projects – the design and ownership of computer networks, now used by billions of people. How did so many people end up being that dependent on a single search engine? Why are we repeating the Microsoft saga once again? It seems boring to complain about a monopoly in the making when average Internet users have such a multitude of tools at their disposal to distribute power. One possible way to overcome this predicament would be to positively redefine Heidegger’s Gerede. Instead of a culture of complaint that dreams of an undisturbed offline life and radical measures to filter out the noise, it is time to openly confront the trivial forms of Dasein today found in blogs, text messages and computer games. Intellectuals should no longer portray Internet users as secondary amateurs, cut off from a primary and primordial relationship with the world. There is a greater issue at stake and it requires venturing into the politics of informatic life. It is time to address the emergence of a new type of corporation that is rapidly transcending the Internet: Google.

The World Wide Web, which should have realized the infinite library Borges described in his short story The Library of Babel (1941), is seen by many of its critics as nothing but a variation of Orwell’s Big Brother (1948). The ruler, in this case, has turned from an evil monster into a collection of cool youngsters whose corporate responsibility slogan is “Don’t be evil”. Guided by a much older and experienced generation of IT gurus (Eric Schmidt), Internet pioneers (Vint Cerf) and economists (Hal Varian), Google has expanded so fast, and in such a wide variety of fields, that there is virtually no critic, academic or business journalist who has been able to keep up with the scope and speed with which Google developed in recent years. New applications and services pile up like unwanted Christmas presents. Just add Google’s free email service Gmail, the video sharing platform YouTube, the social networking site Orkut, GoogleMaps and GoogleEarth, its main revenue service AdWords with the Pay-Per-Click advertisements, office applications such as Calendar, Talks and Docs. Google not only competes with Microsoft and Yahoo, but also with entertainment firms, public libraries (through its massive book scanning program) and even telecom firms. Believe it or not, the Google Phone is coming soon. I recently heard a less geeky family member saying that she had heard that Google was much better and easier to use than the Internet. It sounded cute, but she was right. Not only has Google become the better Internet, it is taking over software tasks from your own computer so that you can access these data from any terminal or handheld device. Apple’s MacBook Air is a further indication of the migration of data to privately controlled storage bunkers. Security and privacy of information are rapidly becoming the new economy and technology of control. And the majority of users, and indeed companies, are happily abandoning the power to self-govern their informational resources.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]