For readers of thediagonal in North America “neurobollocks” would roughly translate to “neurobullshit”.

For readers of thediagonal in North America “neurobollocks” would roughly translate to “neurobullshit”.

So what is this growing “neuro-trend”, why is there an explosion in “neuro-babble” and all things with a “neuro-” prefix, and is Malcolm Gladwell to blame?

[div class=attrib]From the New Statesman:[end-div]

An intellectual pestilence is upon us. Shop shelves groan with books purporting to explain, through snazzy brain-imaging studies, not only how thoughts and emotions function, but how politics and religion work, and what the correct answers are to age-old philosophical controversies. The dazzling real achievements of brain research are routinely pressed into service for questions they were never designed to answer. This is the plague of neuroscientism – aka neurobabble, neurobollocks, or neurotrash – and it’s everywhere.

In my book-strewn lodgings, one literally trips over volumes promising that “the deepest mysteries of what makes us who we are are gradually being unravelled” by neuroscience and cognitive psychology. (Even practising scientists sometimes make such grandiose claims for a general audience, perhaps urged on by their editors: that quotation is from the psychologist Elaine Fox’s interesting book on “the new science of optimism”, Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain, published this summer.) In general, the “neural” explanation has become a gold standard of non-fiction exegesis, adding its own brand of computer-assisted lab-coat bling to a whole new industry of intellectual quackery that affects to elucidate even complex sociocultural phenomena. Chris Mooney’s The Republican Brain: the Science of Why They Deny Science – and Reality disavows “reductionism” yet encourages readers to treat people with whom they disagree more as pathological specimens of brain biology than as rational interlocutors.

The New Atheist polemicist Sam Harris, in The Moral Landscape, interprets brain and other research as showing that there are objective moral truths, enthusiastically inferring – almost as though this were the point all along – that science proves “conservative Islam” is bad.

Happily, a new branch of the neuroscienceexplains everything genre may be created at any time by the simple expedient of adding the prefix “neuro” to whatever you are talking about. Thus, “neuroeconomics” is the latest in a long line of rhetorical attempts to sell the dismal science as a hard one; “molecular gastronomy” has now been trumped in the scientised gluttony stakes by “neurogastronomy”; students of Republican and Democratic brains are doing “neuropolitics”; literature academics practise “neurocriticism”. There is “neurotheology”, “neuromagic” (according to Sleights of Mind, an amusing book about how conjurors exploit perceptual bias) and even “neuromarketing”. Hoping it’s not too late to jump on the bandwagon, I have decided to announce that I, too, am skilled in the newly minted fields of neuroprocrastination and neuroflâneurship.

Illumination is promised on a personal as well as a political level by the junk enlightenment of the popular brain industry. How can I become more creative? How can I make better decisions? How can I be happier? Or thinner? Never fear: brain research has the answers. It is self-help armoured in hard science. Life advice is the hook for nearly all such books. (Some cram the hard sell right into the title – such as John B Arden’s Rewire Your Brain: Think Your Way to a Better Life.) Quite consistently, heir recommendations boil down to a kind of neo- Stoicism, drizzled with brain-juice. In a selfcongratulatory egalitarian age, you can no longer tell people to improve themselves morally. So self-improvement is couched in instrumental, scientifically approved terms.

The idea that a neurological explanation could exhaust the meaning of experience was already being mocked as “medical materialism” by the psychologist William James a century ago. And today’s ubiquitous rhetorical confidence about how the brain works papers over a still-enormous scientific uncertainty. Paul Fletcher, professor of health neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, says that he gets “exasperated” by much popular coverage of neuroimaging research, which assumes that “activity in a brain region is the answer to some profound question about psychological processes. This is very hard to justify given how little we currently know about what different regions of the brain actually do.” Too often, he tells me in an email correspondence, a popular writer will “opt for some sort of neuro-flapdoodle in which a highly simplistic and questionable point is accompanied by a suitably grand-sounding neural term and thus acquires a weightiness that it really doesn’t deserve. In my view, this is no different to some mountebank selling quacksalve by talking about the physics of water molecules’ memories, or a beautician talking about action liposomes.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Amazon.[end-div]

QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No.

QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No. The long-term downward trend in the number injuries to young children is no longer. Sadly, urgent care and emergency room doctors are now seeing more children aged 0-14 years with unintentional injuries. While the exact causes are yet to be determined, there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that points to distraction among patents and supervisors — it’s the texting stupid!

The long-term downward trend in the number injuries to young children is no longer. Sadly, urgent care and emergency room doctors are now seeing more children aged 0-14 years with unintentional injuries. While the exact causes are yet to be determined, there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that points to distraction among patents and supervisors — it’s the texting stupid!

Social media is great for notifying members in one’s circle of events in the here and now. Of course, most events turn out to be rather trivial, of the “what I ate for dinner” kind. However, social media also has a role in spreading word of more momentous social and political events; the Arab Spring comes to mind.

Social media is great for notifying members in one’s circle of events in the here and now. Of course, most events turn out to be rather trivial, of the “what I ate for dinner” kind. However, social media also has a role in spreading word of more momentous social and political events; the Arab Spring comes to mind.

Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion.

Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion. Product driven companies, inventors from all backgrounds and market researchers have long studied how some innovations take off while others fizzle. So, why do some innovations gain traction? Given two similar but competing inventions, what factors lead to one eclipsing the other? Why do some pioneering ideas and inventions fail only to succeed from a different instigator years, sometimes decades, later? Answers to these questions would undoubtedly make many inventors household names, but as is the case in most human endeavors, the process of innovation is murky and more of an art than a science.

Product driven companies, inventors from all backgrounds and market researchers have long studied how some innovations take off while others fizzle. So, why do some innovations gain traction? Given two similar but competing inventions, what factors lead to one eclipsing the other? Why do some pioneering ideas and inventions fail only to succeed from a different instigator years, sometimes decades, later? Answers to these questions would undoubtedly make many inventors household names, but as is the case in most human endeavors, the process of innovation is murky and more of an art than a science. Nathan Myhrvold, former CTO of Microsoft, suggests that the wealthy should “think big” by funding large-scale and long-term innovation. Arguably, this would be a much preferred alternative to the wealthy using their millions to gain (more) political influence in much of the West, especially the United States. Myhrvold is now a backer of TerraPower, a nuclear energy startup.

Nathan Myhrvold, former CTO of Microsoft, suggests that the wealthy should “think big” by funding large-scale and long-term innovation. Arguably, this would be a much preferred alternative to the wealthy using their millions to gain (more) political influence in much of the West, especially the United States. Myhrvold is now a backer of TerraPower, a nuclear energy startup.

Regardless of how flawed old scientific concepts may be researchers have found that it is remarkably difficult for people to give these up and accept sound, new reasoning. Even scientists are creatures of habit.

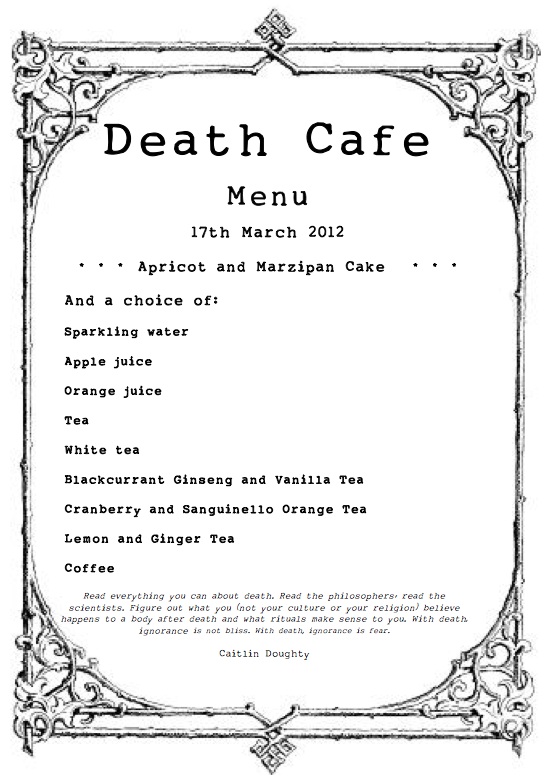

Regardless of how flawed old scientific concepts may be researchers have found that it is remarkably difficult for people to give these up and accept sound, new reasoning. Even scientists are creatures of habit. “Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland.

“Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland. Social scientists have had Generation-Y, also known as “millenials”, under their microscopes for a while. Born between 1982 and 1999, Gen-Y is now coming of age and becoming a force in the workplace displacing aging “boomers” as they retire to the hills. So, researchers are now looking at how Gen-Y is faring inside corporate America. Remember, Gen-Y is the “it’s all about me generation”; members are characterized as typically lazy and spoiled, have a grandiose sense of entitlement, inflated self-esteem and deep emotional fragility. Their predecessors, the baby boomers, on the other hand are often seen as over-bearing, work-obsessed, competitive and narrow-minded. A clash of cultures is taking shape in office cubes across the country as these groups, with such differing personalities and philosophies, tussle within the workplace. However, it may not be all bad, as columnist Emily Matchar, argues below — corporate America needs the kind of shake-up that Gen-Y promises.

Social scientists have had Generation-Y, also known as “millenials”, under their microscopes for a while. Born between 1982 and 1999, Gen-Y is now coming of age and becoming a force in the workplace displacing aging “boomers” as they retire to the hills. So, researchers are now looking at how Gen-Y is faring inside corporate America. Remember, Gen-Y is the “it’s all about me generation”; members are characterized as typically lazy and spoiled, have a grandiose sense of entitlement, inflated self-esteem and deep emotional fragility. Their predecessors, the baby boomers, on the other hand are often seen as over-bearing, work-obsessed, competitive and narrow-minded. A clash of cultures is taking shape in office cubes across the country as these groups, with such differing personalities and philosophies, tussle within the workplace. However, it may not be all bad, as columnist Emily Matchar, argues below — corporate America needs the kind of shake-up that Gen-Y promises. Ayn Rand: anti-collectivist ideologue, standard-bearer for unapologetic individualism and rugged self-reliance, or selfish, fantasist and elitist hypocrite?

Ayn Rand: anti-collectivist ideologue, standard-bearer for unapologetic individualism and rugged self-reliance, or selfish, fantasist and elitist hypocrite? We excerpt an fascinating article from I09 on the association of science fiction to philosophical inquiry. It’s quiet remarkable that this genre of literature can provide such a rich vein for philosophers to mine, often more so than reality itself. Though, it is no coincidence that our greatest authors of science fiction were, and are, amateur philosophers at heart.

We excerpt an fascinating article from I09 on the association of science fiction to philosophical inquiry. It’s quiet remarkable that this genre of literature can provide such a rich vein for philosophers to mine, often more so than reality itself. Though, it is no coincidence that our greatest authors of science fiction were, and are, amateur philosophers at heart.

A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague.

A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague. Robert J. Samuelson paints a sobering picture of the once credible and seemingly attainable American Dream — the generational progress of upward mobility is no longer a given. He is the author of “The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence”.

Robert J. Samuelson paints a sobering picture of the once credible and seemingly attainable American Dream — the generational progress of upward mobility is no longer a given. He is the author of “The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence”. The United States is gripped by political deadlock. The Do-Nothing Congress consistently gets lower approval ratings than our banks, Paris Hilton, lawyers and BP during the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico. This stasis is driven by seemingly intractable ideological beliefs and a no-compromise attitude from both the left and right sides of the aisle.

The United States is gripped by political deadlock. The Do-Nothing Congress consistently gets lower approval ratings than our banks, Paris Hilton, lawyers and BP during the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico. This stasis is driven by seemingly intractable ideological beliefs and a no-compromise attitude from both the left and right sides of the aisle.

The United States is often cited as the most generous nation on Earth. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most violent, having one of the highest murder rates of any industrialized country. Why this tragic paradox?

The United States is often cited as the most generous nation on Earth. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most violent, having one of the highest murder rates of any industrialized country. Why this tragic paradox? We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions.

We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions.