Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

[div class=attrib]According to Wikipedia:[end-div]

He wrote the Comedy in a language he called “Italian”, in some sense an amalgamated literary language mostly based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, with some elements of Latin and of the other regional dialects. The aim was to deliberately reach a readership throughout Italy, both laymen, clergymen and other poets. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression. In French, Italian is sometimes nicknamed la langue de Dante. Publishing in the vernacular language marked Dante as one of the first (among others such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio) to break free from standards of publishing in only Latin (the language of liturgy, history, and scholarship in general, but often also of lyric poetry). This break set a precedent and allowed more literature to be published for a wider audience—setting the stage for greater levels of literacy in the future.

By Dante Alighieri

(translated by the Rev. H. F. Cary)

– Inferno, Canto I

In the midway of this our mortal life,

I found me in a gloomy wood, astray

Gone from the path direct: and e’en to tell

It were no easy task, how savage wild

That forest, how robust and rough its growth,

Which to remember only, my dismay

Renews, in bitterness not far from death.

Yet to discourse of what there good befell,

All else will I relate discover’d there.

How first I enter’d it I scarce can say,

Such sleepy dullness in that instant weigh’d

My senses down, when the true path I left,

But when a mountain’s foot I reach’d, where clos’d

The valley, that had pierc’d my heart with dread,

I look’d aloft, and saw his shoulders broad

Already vested with that planet’s beam,

Who leads all wanderers safe through every way.

Then was a little respite to the fear,

That in my heart’s recesses deep had lain,

All of that night, so pitifully pass’d:

And as a man, with difficult short breath,

Forespent with toiling, ‘scap’d from sea to shore,

Turns to the perilous wide waste, and stands

At gaze; e’en so my spirit, that yet fail’d

Struggling with terror, turn’d to view the straits,

That none hath pass’d and liv’d. My weary frame

After short pause recomforted, again

I journey’d on over that lonely steep,

The hinder foot still firmer. Scarce the ascent

Began, when, lo! a panther, nimble, light,

And cover’d with a speckled skin, appear’d,

Nor, when it saw me, vanish’d, rather strove

To check my onward going; that ofttimes

With purpose to retrace my steps I turn’d.

The hour was morning’s prime, and on his way

Aloft the sun ascended with those stars,

That with him rose, when Love divine first mov’d

Those its fair works: so that with joyous hope

All things conspir’d to fill me, the gay skin

Of that swift animal, the matin dawn

And the sweet season. Soon that joy was chas’d,

And by new dread succeeded, when in view

A lion came, ‘gainst me, as it appear’d,

With his head held aloft and hunger-mad,

That e’en the air was fear-struck. A she-wolf

Was at his heels, who in her leanness seem’d

Full of all wants, and many a land hath made

Disconsolate ere now. She with such fear

O’erwhelmed me, at the sight of her appall’d,

That of the height all hope I lost. As one,

Who with his gain elated, sees the time

When all unwares is gone, he inwardly

Mourns with heart-griping anguish; such was I,

Haunted by that fell beast, never at peace,

Who coming o’er against me, by degrees

Impell’d me where the sun in silence rests.

While to the lower space with backward step

I fell, my ken discern’d the form one of one,

Whose voice seem’d faint through long disuse of speech.

When him in that great desert I espied,

“Have mercy on me!” cried I out aloud,

“Spirit! or living man! what e’er thou be!”

He answer’d: “Now not man, man once I was,

And born of Lombard parents, Mantuana both

By country, when the power of Julius yet

Was scarcely firm. At Rome my life was past

Beneath the mild Augustus, in the time

Of fabled deities and false. A bard

Was I, and made Anchises’ upright son

The subject of my song, who came from Troy,

When the flames prey’d on Ilium’s haughty towers.

But thou, say wherefore to such perils past

Return’st thou? wherefore not this pleasant mount

Ascendest, cause and source of all delight?”

“And art thou then that Virgil, that well-spring,

From which such copious floods of eloquence

Have issued?” I with front abash’d replied.

“Glory and light of all the tuneful train!

May it avail me that I long with zeal

Have sought thy volume, and with love immense

Have conn’d it o’er. My master thou and guide!

Thou he from whom alone I have deriv’d

That style, which for its beauty into fame

Exalts me. See the beast, from whom I fled.

O save me from her, thou illustrious sage!

“For every vein and pulse throughout my frame

She hath made tremble.” He, soon as he saw

That I was weeping, answer’d, “Thou must needs

Another way pursue, if thou wouldst ‘scape

From out that savage wilderness. This beast,

At whom thou criest, her way will suffer none

To pass, and no less hindrance makes than death:

So bad and so accursed in her kind,

That never sated is her ravenous will,

Still after food more craving than before.

To many an animal in wedlock vile

She fastens, and shall yet to many more,

Until that greyhound come, who shall destroy

Her with sharp pain. He will not life support

By earth nor its base metals, but by love,

Wisdom, and virtue, and his land shall be

The land ‘twixt either Feltro. In his might

Shall safety to Italia’s plains arise,

For whose fair realm, Camilla, virgin pure,

Nisus, Euryalus, and Turnus fell.

He with incessant chase through every town

Shall worry, until he to hell at length

Restore her, thence by envy first let loose.

I for thy profit pond’ring now devise,

That thou mayst follow me, and I thy guide

Will lead thee hence through an eternal space,

Where thou shalt hear despairing shrieks, and see

Spirits of old tormented, who invoke

A second death; and those next view, who dwell

Content in fire, for that they hope to come,

Whene’er the time may be, among the blest,

Into whose regions if thou then desire

T’ ascend, a spirit worthier then I

Must lead thee, in whose charge, when I depart,

Thou shalt be left: for that Almighty King,

Who reigns above, a rebel to his law,

Adjudges me, and therefore hath decreed,

That to his city none through me should come.

He in all parts hath sway; there rules, there holds

His citadel and throne. O happy those,

Whom there he chooses!” I to him in few:

“Bard! by that God, whom thou didst not adore,

I do beseech thee (that this ill and worse

I may escape) to lead me, where thou saidst,

That I Saint Peter’s gate may view, and those

Who as thou tell’st, are in such dismal plight.”

Onward he mov’d, I close his steps pursu’d.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire poem here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Dante Alighieri, engraving after the fresco in Bargello Chapel, painted by Giotto di Bondone. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

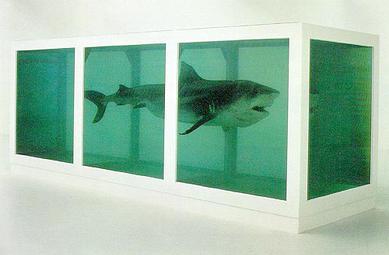

Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years.

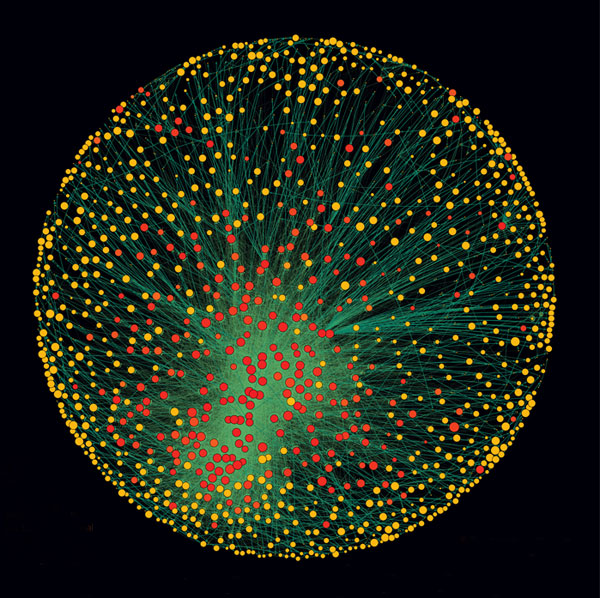

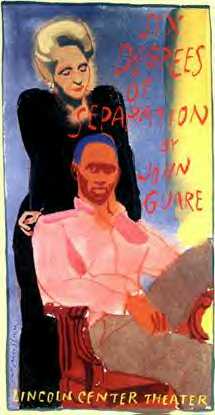

Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years. Six degrees of separation is commonly held urban myth that on average everyone on Earth is six connections or less away from any other person. That is, through a chain of friend of a friend (of a friend, etc) relationships you can find yourself linked to the President, the Chinese Premier, a farmer on the steppes of Mongolia, Nelson Mandela, the editor of theDiagonal, and any one of the other 7 billion people on the planet.

Six degrees of separation is commonly held urban myth that on average everyone on Earth is six connections or less away from any other person. That is, through a chain of friend of a friend (of a friend, etc) relationships you can find yourself linked to the President, the Chinese Premier, a farmer on the steppes of Mongolia, Nelson Mandela, the editor of theDiagonal, and any one of the other 7 billion people on the planet.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language. The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

The hippies of the sixties wanted love; the beatniks sought transcendence. Then came the punks, who were all about rage. The slackers and generation X stood for apathy and worry. And, now coming of age we have generation Y, also known as the “millennials”, whose birthdays fall roughly between 1982-2000.

The hippies of the sixties wanted love; the beatniks sought transcendence. Then came the punks, who were all about rage. The slackers and generation X stood for apathy and worry. And, now coming of age we have generation Y, also known as the “millennials”, whose birthdays fall roughly between 1982-2000. Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers.

Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers. A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy.

A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy. Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that.

Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that. The United States spends around $2.5 trillion per year on health care. Approximately 14 percent of this is administrative spending. That’s $360 billion, yes, billion with a ‘b’, annually. And, by all accounts a significant proportion of this huge sum is duplicate, redundant, wasteful and unnecessary spending — that’s a lot of paperwork.

The United States spends around $2.5 trillion per year on health care. Approximately 14 percent of this is administrative spending. That’s $360 billion, yes, billion with a ‘b’, annually. And, by all accounts a significant proportion of this huge sum is duplicate, redundant, wasteful and unnecessary spending — that’s a lot of paperwork. The unfolding financial crises and political upheavals in Europe have taken several casualties. Notably, the fall of both leaders and their governments in Greece and Italy. Both have been replaced by so-called “technocrats”. So, what is a technocrat and why? State explains.

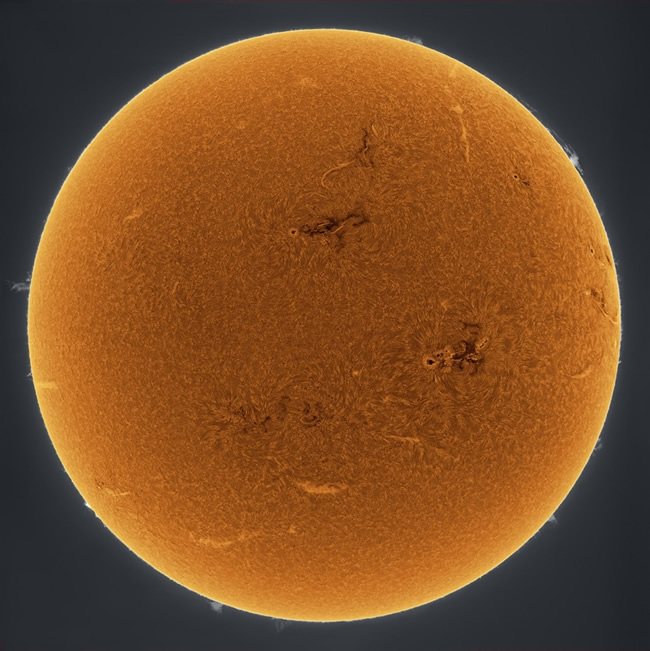

The unfolding financial crises and political upheavals in Europe have taken several casualties. Notably, the fall of both leaders and their governments in Greece and Italy. Both have been replaced by so-called “technocrats”. So, what is a technocrat and why? State explains. Long before the first galaxy clusters and the first galaxies appeared in our universe, and before the first stars, came the first basic elements — hydrogen, helium and lithium.

Long before the first galaxy clusters and the first galaxies appeared in our universe, and before the first stars, came the first basic elements — hydrogen, helium and lithium.

In early 2010 a Japanese research team grew retina-like structures from a culture of mouse embryonic stem cells. Now, only a year later, the same team at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology announced their success in growing a much more complex structure following a similar process — a mouse pituitary gland. This is seen as another major step towards bioengineering replacement organs for human transplantation.

In early 2010 a Japanese research team grew retina-like structures from a culture of mouse embryonic stem cells. Now, only a year later, the same team at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology announced their success in growing a much more complex structure following a similar process — a mouse pituitary gland. This is seen as another major step towards bioengineering replacement organs for human transplantation. [div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div] Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin.

Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin.