Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

[div class=attrib]According to Wikipedia:[end-div]

He wrote the Comedy in a language he called “Italian”, in some sense an amalgamated literary language mostly based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, with some elements of Latin and of the other regional dialects. The aim was to deliberately reach a readership throughout Italy, both laymen, clergymen and other poets. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression. In French, Italian is sometimes nicknamed la langue de Dante. Publishing in the vernacular language marked Dante as one of the first (among others such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio) to break free from standards of publishing in only Latin (the language of liturgy, history, and scholarship in general, but often also of lyric poetry). This break set a precedent and allowed more literature to be published for a wider audience—setting the stage for greater levels of literacy in the future.

By Dante Alighieri

(translated by the Rev. H. F. Cary)

– Inferno, Canto I

In the midway of this our mortal life,

I found me in a gloomy wood, astray

Gone from the path direct: and e’en to tell

It were no easy task, how savage wild

That forest, how robust and rough its growth,

Which to remember only, my dismay

Renews, in bitterness not far from death.

Yet to discourse of what there good befell,

All else will I relate discover’d there.

How first I enter’d it I scarce can say,

Such sleepy dullness in that instant weigh’d

My senses down, when the true path I left,

But when a mountain’s foot I reach’d, where clos’d

The valley, that had pierc’d my heart with dread,

I look’d aloft, and saw his shoulders broad

Already vested with that planet’s beam,

Who leads all wanderers safe through every way.

Then was a little respite to the fear,

That in my heart’s recesses deep had lain,

All of that night, so pitifully pass’d:

And as a man, with difficult short breath,

Forespent with toiling, ‘scap’d from sea to shore,

Turns to the perilous wide waste, and stands

At gaze; e’en so my spirit, that yet fail’d

Struggling with terror, turn’d to view the straits,

That none hath pass’d and liv’d. My weary frame

After short pause recomforted, again

I journey’d on over that lonely steep,

The hinder foot still firmer. Scarce the ascent

Began, when, lo! a panther, nimble, light,

And cover’d with a speckled skin, appear’d,

Nor, when it saw me, vanish’d, rather strove

To check my onward going; that ofttimes

With purpose to retrace my steps I turn’d.

The hour was morning’s prime, and on his way

Aloft the sun ascended with those stars,

That with him rose, when Love divine first mov’d

Those its fair works: so that with joyous hope

All things conspir’d to fill me, the gay skin

Of that swift animal, the matin dawn

And the sweet season. Soon that joy was chas’d,

And by new dread succeeded, when in view

A lion came, ‘gainst me, as it appear’d,

With his head held aloft and hunger-mad,

That e’en the air was fear-struck. A she-wolf

Was at his heels, who in her leanness seem’d

Full of all wants, and many a land hath made

Disconsolate ere now. She with such fear

O’erwhelmed me, at the sight of her appall’d,

That of the height all hope I lost. As one,

Who with his gain elated, sees the time

When all unwares is gone, he inwardly

Mourns with heart-griping anguish; such was I,

Haunted by that fell beast, never at peace,

Who coming o’er against me, by degrees

Impell’d me where the sun in silence rests.

While to the lower space with backward step

I fell, my ken discern’d the form one of one,

Whose voice seem’d faint through long disuse of speech.

When him in that great desert I espied,

“Have mercy on me!” cried I out aloud,

“Spirit! or living man! what e’er thou be!”

He answer’d: “Now not man, man once I was,

And born of Lombard parents, Mantuana both

By country, when the power of Julius yet

Was scarcely firm. At Rome my life was past

Beneath the mild Augustus, in the time

Of fabled deities and false. A bard

Was I, and made Anchises’ upright son

The subject of my song, who came from Troy,

When the flames prey’d on Ilium’s haughty towers.

But thou, say wherefore to such perils past

Return’st thou? wherefore not this pleasant mount

Ascendest, cause and source of all delight?”

“And art thou then that Virgil, that well-spring,

From which such copious floods of eloquence

Have issued?” I with front abash’d replied.

“Glory and light of all the tuneful train!

May it avail me that I long with zeal

Have sought thy volume, and with love immense

Have conn’d it o’er. My master thou and guide!

Thou he from whom alone I have deriv’d

That style, which for its beauty into fame

Exalts me. See the beast, from whom I fled.

O save me from her, thou illustrious sage!

“For every vein and pulse throughout my frame

She hath made tremble.” He, soon as he saw

That I was weeping, answer’d, “Thou must needs

Another way pursue, if thou wouldst ‘scape

From out that savage wilderness. This beast,

At whom thou criest, her way will suffer none

To pass, and no less hindrance makes than death:

So bad and so accursed in her kind,

That never sated is her ravenous will,

Still after food more craving than before.

To many an animal in wedlock vile

She fastens, and shall yet to many more,

Until that greyhound come, who shall destroy

Her with sharp pain. He will not life support

By earth nor its base metals, but by love,

Wisdom, and virtue, and his land shall be

The land ‘twixt either Feltro. In his might

Shall safety to Italia’s plains arise,

For whose fair realm, Camilla, virgin pure,

Nisus, Euryalus, and Turnus fell.

He with incessant chase through every town

Shall worry, until he to hell at length

Restore her, thence by envy first let loose.

I for thy profit pond’ring now devise,

That thou mayst follow me, and I thy guide

Will lead thee hence through an eternal space,

Where thou shalt hear despairing shrieks, and see

Spirits of old tormented, who invoke

A second death; and those next view, who dwell

Content in fire, for that they hope to come,

Whene’er the time may be, among the blest,

Into whose regions if thou then desire

T’ ascend, a spirit worthier then I

Must lead thee, in whose charge, when I depart,

Thou shalt be left: for that Almighty King,

Who reigns above, a rebel to his law,

Adjudges me, and therefore hath decreed,

That to his city none through me should come.

He in all parts hath sway; there rules, there holds

His citadel and throne. O happy those,

Whom there he chooses!” I to him in few:

“Bard! by that God, whom thou didst not adore,

I do beseech thee (that this ill and worse

I may escape) to lead me, where thou saidst,

That I Saint Peter’s gate may view, and those

Who as thou tell’st, are in such dismal plight.”

Onward he mov’d, I close his steps pursu’d.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire poem here.[end-div]

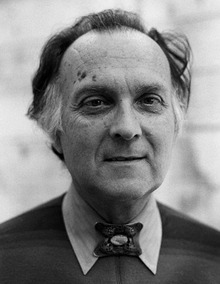

[div class=attrib]Image: Dante Alighieri, engraving after the fresco in Bargello Chapel, painted by Giotto di Bondone. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

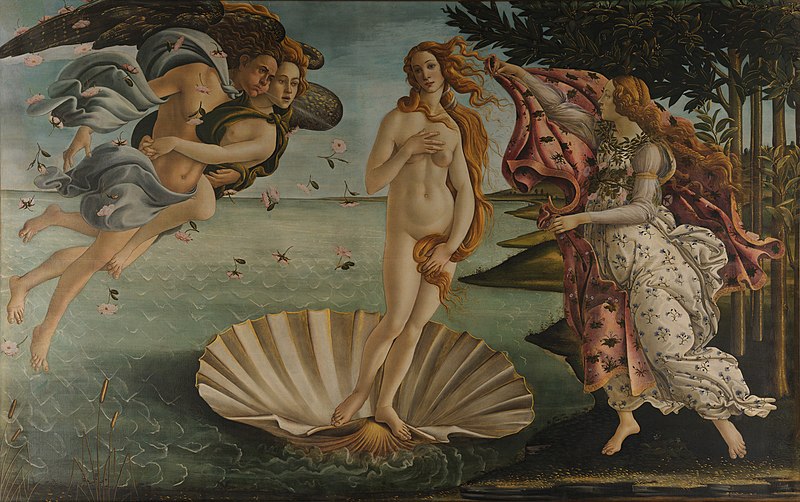

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

Robert Hayden is generally accepted as one of the premier authors of African American poetry. His expertly crafted poems focusing on the black historical experience earned him numerous awards.

Robert Hayden is generally accepted as one of the premier authors of African American poetry. His expertly crafted poems focusing on the black historical experience earned him numerous awards. In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD.

In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD. Fahrenheit 2,451 may well be the temperature at which the glass in your Kindle or Nook eReader is likely to melt. This may give Ray Bradbury mixed feelings.

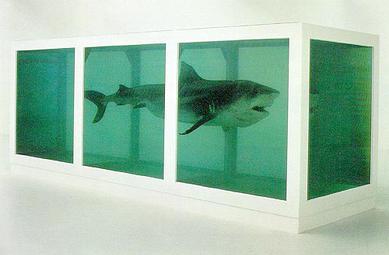

Fahrenheit 2,451 may well be the temperature at which the glass in your Kindle or Nook eReader is likely to melt. This may give Ray Bradbury mixed feelings. Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years.

Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years. Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language. The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes. Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers.

Daniel Kahneman brings together for the first time his decades of groundbreaking research and profound thinking in social psychology and cognitive science in his new book, Thinking Fast and Slow. He presents his current understanding of judgment and decision making and offers insight into how we make choices in our daily lives. Importantly, Kahneman describes how we can identify and overcome the cognitive biases that frequently lead us astray. This is an important work by one of our leading thinkers. A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy.

A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy. Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin.

Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin. Joy Harjo is an acclaimed poet, musician and noted teacher. Her poetry is grounded in the United States’ Southwest and often encompasses Native American stories and values.

Joy Harjo is an acclaimed poet, musician and noted teacher. Her poetry is grounded in the United States’ Southwest and often encompasses Native American stories and values.

Tens of thousands of independent bookstores have disappeared from the United States and Europe over the last decade. Even mega-chains like Borders have fallen prey to monumental shifts in the distribution of ideas and content. The very notion of the physical book is under increasing threat from the accelerating momentum of digitalization.

Tens of thousands of independent bookstores have disappeared from the United States and Europe over the last decade. Even mega-chains like Borders have fallen prey to monumental shifts in the distribution of ideas and content. The very notion of the physical book is under increasing threat from the accelerating momentum of digitalization. Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource.

Charles Fishman has a fascinating new book entitled The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. In it Fishman examines the origins of water on our planet and postulates an all to probable future where water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource. This week, theDiagonal focuses its energies on that most precious of natural resources — water.

This week, theDiagonal focuses its energies on that most precious of natural resources — water.

Ushering in our week of articles focused mostly on death and loss is a classic piece by Welshman, Dylan Thomas. Although Thomas’ literary legacy is colored by his legendary drinking and philandering, many critics now seem to agree that his poetry belongs in the same class as that of W.H. Auden.

Ushering in our week of articles focused mostly on death and loss is a classic piece by Welshman, Dylan Thomas. Although Thomas’ literary legacy is colored by his legendary drinking and philandering, many critics now seem to agree that his poetry belongs in the same class as that of W.H. Auden. Tomas Tranströmer is one of Sweden’s leading poets. He studied poetry and psychology at the University of Stockholm. Tranströmer was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize for Literature “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality”.

Tomas Tranströmer is one of Sweden’s leading poets. He studied poetry and psychology at the University of Stockholm. Tranströmer was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize for Literature “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality”. [div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div] The Autumnal Equinox finally ushers in some cooler temperatures for the northern hemisphere, and with that we reflect on this most human of seasons courtesy of a poem by Archibald MacLeish.

The Autumnal Equinox finally ushers in some cooler temperatures for the northern hemisphere, and with that we reflect on this most human of seasons courtesy of a poem by Archibald MacLeish.

A poem by Anthony Hecht this week. On Hecht, Poetry Foundation remarks, “[o]ne of the leading voices of his generation, Anthony Hecht’s poetry is known for its masterful use of traditional forms and linguistic control.”

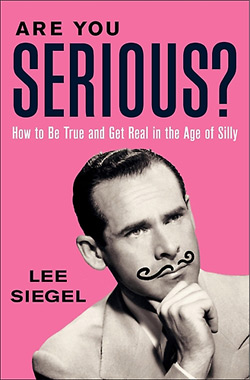

A poem by Anthony Hecht this week. On Hecht, Poetry Foundation remarks, “[o]ne of the leading voices of his generation, Anthony Hecht’s poetry is known for its masterful use of traditional forms and linguistic control.” “You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate:

“You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate: This week theDiagonal triangulates its sights on the topic of language and communication. So, we introduce an apt poem by Robert Duncan. Of Robert Duncan, Poetry Foundation writes:

This week theDiagonal triangulates its sights on the topic of language and communication. So, we introduce an apt poem by Robert Duncan. Of Robert Duncan, Poetry Foundation writes: Labor Day traditionally signals the end of summer. A poem by Gwendolyn Brooks sets the mood. She was the first black author to win the Pulitzer Prize.

Labor Day traditionally signals the end of summer. A poem by Gwendolyn Brooks sets the mood. She was the first black author to win the Pulitzer Prize. A poem by Billy Collins ushers in another week. Collins served two terms as the U.S. Poet Laureate, from 2001-2003. He is known for poetry imbued with leftfield humor and deep insight.

A poem by Billy Collins ushers in another week. Collins served two terms as the U.S. Poet Laureate, from 2001-2003. He is known for poetry imbued with leftfield humor and deep insight.

Skeptic

Skeptic