[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div]

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed–

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

(It never was America to me.)

O, let my land be a land where Liberty

Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath,

But opportunity is real, and life is free,

Equality is in the air we breathe.

(There’s never been equality for me,

Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”)

Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark?

And who are you that draws your veil across the stars?

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek–

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

Of work the men! Of take the pay!

Of owning everything for one’s own greed!

I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil.

I am the worker sold to the machine.

I am the Negro, servant to you all.

I am the people, humble, hungry, mean–

Hungry yet today despite the dream.

Beaten yet today–O, Pioneers!

I am the man who never got ahead,

The poorest worker bartered through the years.

Yet I’m the one who dreamt our basic dream

In the Old World while still a serf of kings,

Who dreamt a dream so strong, so brave, so true,

That even yet its mighty daring sings

In every brick and stone, in every furrow turned

That’s made America the land it has become.

O, I’m the man who sailed those early seas

In search of what I meant to be my home–

For I’m the one who left dark Ireland’s shore,

And Poland’s plain, and England’s grassy lea,

And torn from Black Africa’s strand I came

To build a “homeland of the free.”

The free?

Who said the free? Not me?

Surely not me? The millions on relief today?

The millions shot down when we strike?

The millions who have nothing for our pay?

For all the dreams we’ve dreamed

And all the songs we’ve sung

And all the hopes we’ve held

And all the flags we’ve hung,

The millions who have nothing for our pay–

Except the dream that’s almost dead today.

O, let America be America again–

The land that never has been yet–

And yet must be–the land where every man is free.

The land that’s mine–the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME–

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain,

Must bring back our mighty dream again.

Sure, call me any ugly name you choose–

The steel of freedom does not stain.

From those who live like leeches on the people’s lives,

We must take back our land again,

America!

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath–

America will be!

Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain–

All, all the stretch of these great green states–

And make America again!

Ushering in this week’s focus on the brain and the cognitive sciences is an Emily Dickinson poem.

Ushering in this week’s focus on the brain and the cognitive sciences is an Emily Dickinson poem.

A poignant, poetic view of our relationships, increasingly mediated and recalled for us through technology. Conor O’Callaghan’s poem ushers in this week’s collection of articles at theDiagonal focused on technology.

A poignant, poetic view of our relationships, increasingly mediated and recalled for us through technology. Conor O’Callaghan’s poem ushers in this week’s collection of articles at theDiagonal focused on technology. Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

A recently opened solo art show takes an fascinating inside peek at the cryonics industry. Entitled “The Prospect of Immortality” the show features photography by Murray Ballard. Ballard’s collection of images follows a 5-year investigation of cryonics in England, the United States and Russia. Cryonics is the practice of freezing the human body just after death in the hope that future science will one day have the capability of restoring it to life.

A recently opened solo art show takes an fascinating inside peek at the cryonics industry. Entitled “The Prospect of Immortality” the show features photography by Murray Ballard. Ballard’s collection of images follows a 5-year investigation of cryonics in England, the United States and Russia. Cryonics is the practice of freezing the human body just after death in the hope that future science will one day have the capability of restoring it to life. A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes,

A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes, Monday’s poem authored by William Meredith, was selected for it is in keeping with our

Monday’s poem authored by William Meredith, was selected for it is in keeping with our  The next time you wander through an art gallery and feel lightheaded after seeing a Monroe silkscreen by Warhol, or feel reflective and soothed by a scene from Monet’s garden you’ll be in good company. New research shows that the body reacts to art not just our grey matter.

The next time you wander through an art gallery and feel lightheaded after seeing a Monroe silkscreen by Warhol, or feel reflective and soothed by a scene from Monet’s garden you’ll be in good company. New research shows that the body reacts to art not just our grey matter. Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div] Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable.

Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div] Classic dystopian novels from the likes of

Classic dystopian novels from the likes of

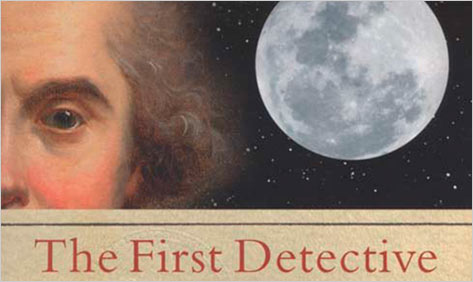

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq.

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq. [div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Salon:[end-div]

Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath?

Hilarious and disturbing. I suspect Jon Ronson would strike a couple of checkmarks in the Hare PCL-R Checklist against my name for finding his latest work both hilarious and disturbing. Would this, perhaps, make me a psychopath?

[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Let America Be America Again, Langston Hughes[end-div] Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process.

Solar is a timely, hilarious novel from the author of Atonement that examines the self-absorption and (self-)deceptions of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Michael Beard. With his best work many decades behind him Beard trades on his professional reputation to earn continuing financial favor, and maintain influence and respect amongst his peers. And, with his personal life in an ever-decreasing spiral, with his fifth marriage coming to an end, Beard manages to entangle himself in an impossible accident which has the power to re-shape his own world, and the planet in the process. David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies.

David Brooks brings us a detailed journey through the building blocks of the self in his new book, The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement. With his insight and gift for narrative Brooks weaves an engaging and compelling story of Erica and Harold. Brooks uses the characters of Erica and Harold as platforms on which he visualizes the results of numerous psychological, social and cultural studies. Placed in contemporary time the two characters show us a holistic picture in practical terms of the unconscious effects of physical and social context on behavioral and character traits. The narrative takes us through typical life events and stages: infancy, childhood, school, parenting, work-life, attachment, aging. At each stage, Brooks illustrates his views of the human condition by selecting a flurry of facts and anecdotal studies.