Like it or not, Facebook is becoming the de-facto medium of choice for managing relationships with friends, colleagues, and lovers (past, present and future). Another fascinating infographic — this one courtesy of onlinedating.org:

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

PARIS — You’re reminded hourly, even while walking along the slow-moving Seine or staring at sculpted marble bodies under the Louvre’s high ceilings, that the old continent is crumbling. They’re slouching toward a gerontocracy, these Europeans. Their banks are teetering. They can’t handle immigration. Greece is broke, and three other nations are not far behind. In a half-dozen languages, the papers shout: crisis!

If the euro fails, as Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany said, then Europe fails. That means a recession here, and a likely one at home, which will be blamed on President Obama, and then Rick Perry will get elected, and the leader of the free world will be somebody who thinks the earth is only a few thousand years old.

You see where it’s all going, this endless “whither the euro question.” So, you think of something else, the Parisian way. You think of what these people can eat on a given day: pain au chocolat for breakfast, soupe a? l’oignon gratine?e topped by melted gruyere for lunch and foie gras for dinner, as a starter.

And then you look around: how can they live like this? Where are all the fat people? It’s a question that has long tormented visitors. These French, they eat anything they damn well please, drink like Mad Men and are healthier than most Americans. And of course, their medical care is free and universal, and considered by many to be the best in the world.

… Recent studies indicate that the French are, in fact, getting fatter — just not as much as everyone else. On average, they are where Americans were in the 1970s, when the ballooning of a nation was still in its early stages. But here’s the good news: they may have figured out some way to contain the biggest global health threat of our time, for France is now one of a handful of nations where obesity among the young has leveled off.

First, the big picture: Us. We — my fellow Americans — are off the charts on this global pathology. The latest jolt came from papers published last month in The Lancet, projecting that three-fourths of adults in the United States will be overweight or obese by 2020.

Only one state, Colorado, now has an obesity rate under 20 percent (obesity is the higher of the two body-mass indexes, the other being overweight). But that’s not good news. The average bulge of an adult Coloradan has increased 80 percent over the last 15 years. They only stand out by comparison to all other states. Colorado, the least fat state in 2011, would be the heaviest had they reported their current rate of obesity 20 years ago. That’s how much we’ve slipped.

… A study of how the French appear to have curbed childhood obesity shows the issue is not complex. Junk food vending machines were banned in schools. The young were encouraged to exercise more. And school lunches were made healthier.

… But another answer can come from self-discovery. Every kid should experience a fresh peach in August. And an American newly arrived in the City of Light should nibble at a cluster of grapes or some blood-red figs, just as the French do, with that camembert.

[div class=attrib]More from the article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Obesity classification standards illustration courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]

Led by the biologist Richard Dawkins, the author of “The God Delusion,” atheism has taken on a new life in popular religious debate. Dawkins’s brand of atheism is scientific in that it views the “God hypothesis” as obviously inadequate to the known facts. In particular, he employs the facts of evolution to challenge the need to postulate God as the designer of the universe. For atheists like Dawkins, belief in God is an intellectual mistake, and honest thinkers need simply to recognize this and move on from the silliness and abuses associated with religion.

Most believers, however, do not come to religion through philosophical arguments. Rather, their belief arises from their personal experiences of a spiritual world of meaning and values, with God as its center.

In the last few years there has emerged another style of atheism that takes such experiences seriously. One of its best exponents is Philip Kitcher, a professor of philosophy at Columbia. (For a good introduction to his views, see Kitcher’s essay in “The Joy of Secularism,” perceptively discussed last month by James Wood in The New Yorker.)

Instead of focusing on the scientific inadequacy of theistic arguments, Kitcher critically examines the spiritual experiences underlying religious belief, particularly noting that they depend on specific and contingent social and cultural conditions. Your religious beliefs typically depend on the community in which you were raised or live. The spiritual experiences of people in ancient Greece, medieval Japan or 21st-century Saudi Arabia do not lead to belief in Christianity. It seems, therefore, that religious belief very likely tracks not truth but social conditioning. This “cultural relativism” argument is an old one, but Kitcher shows that it is still a serious challenge. (He is also refreshingly aware that he needs to show why a similar argument does not apply to his own position, since atheistic beliefs are themselves often a result of the community in which one lives.)

[div class=attrib]More of the article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Ephesians 2,12 – Greek atheos, courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

Neuroscientists continue to find interesting experimental evidence that we do not have free will. Many philosophers continue to dispute this notion and cite inconclusive results and lack of holistic understanding of decision-making on the part of brain scientists. An article by Kerri Smith over at Nature lays open this contentious and fascinating debate.

Neuroscientists continue to find interesting experimental evidence that we do not have free will. Many philosophers continue to dispute this notion and cite inconclusive results and lack of holistic understanding of decision-making on the part of brain scientists. An article by Kerri Smith over at Nature lays open this contentious and fascinating debate.

[div class=attrib]From Nature:[end-div]

The experiment helped to change John-Dylan Haynes’s outlook on life. In 2007, Haynes, a neuroscientist at the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience in Berlin, put people into a brain scanner in which a display screen flashed a succession of random letters1. He told them to press a button with either their right or left index fingers whenever they felt the urge, and to remember the letter that was showing on the screen when they made the decision. The experiment used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to reveal brain activity in real time as the volunteers chose to use their right or left hands. The results were quite a surprise.

“The first thought we had was ‘we have to check if this is real’,” says Haynes. “We came up with more sanity checks than I’ve ever seen in any other study before.”

The conscious decision to push the button was made about a second before the actual act, but the team discovered that a pattern of brain activity seemed to predict that decision by as many as seven seconds. Long before the subjects were even aware of making a choice, it seems, their brains had already decided.

As humans, we like to think that our decisions are under our conscious control — that we have free will. Philosophers have debated that concept for centuries, and now Haynes and other experimental neuroscientists are raising a new challenge. They argue that consciousness of a decision may be a mere biochemical afterthought, with no influence whatsoever on a person’s actions. According to this logic, they say, free will is an illusion. “We feel we choose, but we don’t,” says Patrick Haggard, a neuroscientist at University College London.

You may have thought you decided whether to have tea or coffee this morning, for example, but the decision may have been made long before you were aware of it. For Haynes, this is unsettling. “I’ll be very honest, I find it very difficult to deal with this,” he says. “How can I call a will ‘mine’ if I don’t even know when it occurred and what it has decided to do?”

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Nature.[end-div]

Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

We excerpt a lengthy interview with Jaron Lanier over at the Edge. Lanier, a pioneer in the sphere of virtual reality, offers some well-laid arguments for and against concentration of market power as enabled by information systems and the internet. Though he leaves his most powerful criticism at the doors of Google. Their (in)famous corporate mantra — “do no evil” — will start to look remarkably disingenuous.

[div class=attrib]From the Edge:[end-div]

I’ve focused quite a lot on how this stealthy component of computation can affect our sense of ourselves, what it is to be a person. But lately I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to economics.

In particular, I’m interested in a pretty simple problem, but one that is devastating. In recent years, many of us have worked very hard to make the Internet grow, to become available to people, and that’s happened. It’s one of the great topics of mankind of this era. Everyone’s into Internet things, and yet we have this huge global economic trouble. If you had talked to anyone involved in it twenty years ago, everyone would have said that the ability for people to inexpensively have access to a tremendous global computation and networking facility ought to create wealth. This ought to create wellbeing; this ought to create this incredible expansion in just people living decently, and in personal liberty. And indeed, some of that’s happened. Yet if you look at the big picture, it obviously isn’t happening enough, if it’s happening at all.

The situation reminds me a little bit of something that is deeply connected, which is the way that computer networks transformed finance. You have more and more complex financial instruments, derivatives and so forth, and high frequency trading, all these extraordinary constructions that would be inconceivable without computation and networking technology.

At the start, the idea was, “Well, this is all in the service of the greater good because we’ll manage risk so much better, and we’ll increase the intelligence with which we collectively make decisions.” Yet if you look at what happened, risk was increased instead of decreased.

… We were doing a great job through the turn of the century. In the ’80s and ’90s, one of the things I liked about being in the Silicon Valley community was that we were growing the middle class. The personal computer revolution could have easily been mostly about enterprises. It could have been about just fighting IBM and getting computers on desks in big corporations or something, instead of this notion of the consumer, ordinary person having access to a computer, of a little mom and pop shop having a computer, and owning their own information. When you own information, you have power. Information is power. The personal computer gave people their own information, and it enabled a lot of lives.

… But at any rate, the Apple idea is that instead of the personal computer model where people own their own information, and everybody can be a creator as well as a consumer, we’re moving towards this iPad, iPhone model where it’s not as adequate for media creation as the real media creation tools, and even though you can become a seller over the network, you have to pass through Apple’s gate to accept what you do, and your chances of doing well are very small, and it’s not a person to person thing, it’s a business through a hub, through Apple to others, and it doesn’t create a middle class, it creates a new kind of upper class.

Google has done something that might even be more destructive of the middle class, which is they’ve said, “Well, since Moore’s law makes computation really cheap, let’s just give away the computation, but keep the data.” And that’s a disaster.

What’s happened now is that we’ve created this new regimen where the bigger your computer servers are, the more smart mathematicians you have working for you, and the more connected you are, the more powerful and rich you are. (Unless you own an oil field, which is the old way.) II benefit from it because I’m close to the big servers, but basically wealth is measured by how close you are to one of the big servers, and the servers have started to act like private spying agencies, essentially.

With Google, or with Facebook, if they can ever figure out how to steal some of Google’s business, there’s this notion that you get all of this stuff for free, except somebody else owns the data, and they use the data to sell access to you, and the ability to manipulate you, to third parties that you don’t necessarily get to know about. The third parties tend to be kind of tawdry.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Jaron Lanier.[end-div]

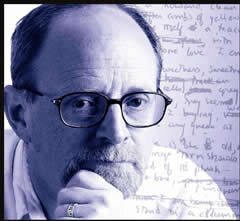

In his book, “The Secret Life of Pronouns”, professor of psychology James Pennebaker describes how our use of words like “I”, “we”, “he”, “she” and “who” reveals a wealth of detail about ourselves including, and very surprisingly, our health and social status.

In his book, “The Secret Life of Pronouns”, professor of psychology James Pennebaker describes how our use of words like “I”, “we”, “he”, “she” and “who” reveals a wealth of detail about ourselves including, and very surprisingly, our health and social status.

[div class=attrib]Excerpts from James Pennebaker’s interview with Scientific American:[end-div]

In the 1980s, my students and I discovered that if people were asked to write about emotional upheavals, their physical health improved. Apparently, putting emotional experiences into language changed the ways people thought about their upheavals. In an attempt to better understand the power of writing, we developed a computerized text analysis program to determine how language use might predict later health improvements.

Much to my surprise, I soon discovered that the ways people used pronouns in their essays predicted whose health would improve the most. Specifically, those people who benefited the most from writing changed in their pronoun use from one essay to another. Pronouns were reflecting people’’s abilities to change perspective.

As I pondered these findings, I started looking at how people used pronouns in other texts — blogs, emails, speeches, class writing assignments, and natural conversation. Remarkably, how people used pronouns was correlated with almost everything I studied. For example, use of first-person singular pronouns (I, me, my) was consistently related to gender, age, social class, honesty, status, personality, and much more.

… In my own work, we have analyzed the collected works of poets, playwrights, and novelists going back to the 1500s to see how their writing changed as they got older. We’ve compared the pronoun use of suicidal versus non-suicidal poets. Basically, poets who eventually commit suicide use I-words more than non-suicidal poets.

The analysis of language style can also serve as a psychological window into authors and their relationships. We have analyzed the poetry of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning and compared it with the history of their marriage. Same thing with Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Using a method we call Language Style Matching, we can isolate changes in the couples’ relationships.

… One of the most interesting results was part of a study my students and I conducted dealing with status in email correspondence. Basically, we discovered that in any interaction, the person with the higher status uses I-words less (yes, less) than people who are low in status. The effects were quite robust and, naturally, I wanted to test this on myself. I always assumed that I was a warm, egalitarian kind of guy who treated people pretty much the same.

I was the same as everyone else. When undergraduates wrote me, their emails were littered with I, me, and my. My response, although quite friendly, was remarkably detached — hardly an I-word graced the page.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Images courtesy of Univesity of Texas at Austin.[end-div]

As any Italian speaker would attest, the moon, of course is utterly feminine. It is “la luna”. Now, to a German it is “der mond”, and very masculine.

As any Italian speaker would attest, the moon, of course is utterly feminine. It is “la luna”. Now, to a German it is “der mond”, and very masculine.

Numerous languages assign a grammatical gender to objects, which in turn influences how people see these objects as either female or male. Yet, researchers have found that sex tends to be ascribed to objects and concepts even in gender-neutral languages. Scientific American reviews this current research.

[div class attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

Gender is so fundamental to the way we understand the world that people are prone to assign a sex to even inanimate objects. We all know someone, or perhaps we are that person, who consistently refers to their computer or car with a gender pronoun (“She’s been running great these past few weeks!”) New research suggests that our tendency to see gender everywhere even applies to abstract ideas such as numbers. Across cultures, people see odd numbers as male and even numbers as female.

Scientists have long known that language can influence how we perceive gender in objects. Some languages consistently refer to certain objects as male or female, and this in turn, influences how speakers of that language think about those objects. Webb Phillips of the Max Planck Institute, Lauren Schmidt of HeadLamp Research, and Lera Boroditsky at Stanford University asked Spanish- and German-speaking bilinguals to rate various objects according to whether they seemed more similar to males or females. They found that people rated each object according to its grammatical gender. For example, Germans see the moon as being more like a man, because the German word for moon is grammatically masculine (“der Mond”). In contrast, Spanish-speakers see the moon as being more like a woman, because in Spanish the word for moon is grammatically feminine (“la Luna”).

Aside from language, objects can also become infused with gender based on their appearance, who typically uses them, and whether they seem to possess the type of characteristics usually associated with men or women. David Gal and James Wilkie of Northwestern University studied how people view gender in everyday objects, such as food and furniture. They found that people see food dishes containing meat as more masculine and salads and sour dairy products as more feminine. People see furniture items, such as tables and trash cans, as more feminine when they feature rounded, rather than sharp, edges.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Scientific American.[end-div]

Well the simple answer is, around 800 spoken languages. Or to be more precise, Papua New Guinea is home to an astounding 830 different languages. New York City comes in a close second, with around 800 spoken languages – and that’s not counting when the United Nations is in session on Manhattan’s East Side. Sadly, some of the rarer tongues spoken in New York and Papua New Guinea, and around the globe for that matter, are rapidly becoming extinct – at the rate of around one language every two weeks.

Well the simple answer is, around 800 spoken languages. Or to be more precise, Papua New Guinea is home to an astounding 830 different languages. New York City comes in a close second, with around 800 spoken languages – and that’s not counting when the United Nations is in session on Manhattan’s East Side. Sadly, some of the rarer tongues spoken in New York and Papua New Guinea, and around the globe for that matter, are rapidly becoming extinct – at the rate of around one language every two weeks.

As the Economist points out a group of linguists in New York City is working to codify some of the city’s most endangered tongues.

[div class=attrib]From the Economist:[end-div]

New York is also home, of course, to a lot of academic linguists, and three of them have got together to create an organisation called the Endangered Language Alliance (ELA), which is ferreting out speakers of unusual tongues from the city’s huddled immigrant masses. The ELA, which was set up last year by Daniel Kaufman, Juliette Blevins and Bob Holman, has worked in detail on 12 languages since its inception. It has codified their grammars, their pronunciations and their word-formation patterns, as well as their songs and legends. Among the specimens in its collection are Garifuna, which is spoken by descendants of African slaves who made their homes on St Vincent after a shipwreck unexpectedly liberated them; Mamuju, from Sulawesi in Indonesia; Mahongwe, a language from Gabon; Shughni, from the Pamirian region of Tajikistan; and an unusual variant of a Mexican language called Totonac.

Each volunteer speaker of a language of interest is first tested with what is known as a Swadesh list. This is a set of 207 high-frequency, slow-to-change words such as parts of the body, colours and basic verbs like eat, drink, sleep and kill. The Swadesh list is intended to ascertain an individual’s fluency before he is taken on. Once he has been accepted, Dr Kaufman and his colleagues start chipping away at the language’s phonology (the sounds of which it is composed) and its syntax (how its meaning is changed by the order of words and phrases). This sort of analysis is the bread and butter of linguistics.

Every so often, though, the researchers come across a bit of jam. The Mahongwe word manono, for example, means “I like” when spoken soft and flat, and “I don’t like” when the first syllable is a tad sharper in tone. Similarly, mbaza could be either “chest” or “council house”. In both cases, the two words are nearly indistinguishable to an English speaker, but yield starkly different patterns when run through a spectrograph. Manono is a particular linguistic oddity, since it uses only tone to differentiate an affirmative from a negative—a phenomenon the ELA has since discovered applies to all verbs in Mahongwe.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Twenty-five years ago, almost no one had a cell phone. Very few of us had digital cameras, and laptop computers belonged only to the very rich. But there is something else—not electronic, but also man-made—that has climbed from the margins of the culture in the 1980s to become a standard accoutrement in upscale neighborhoods across the land: twins.

According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention the U.S. twin rate has skyrocketed from one pair born out of every 53 live births in 1980 to one out of every 31 births in 2008. Where are all these double-babies coming from? And what’s going to happen in years to come—will the multiple-birth rate continue to grow until America ends up a nation of twins?

The twin boom can be explained by changes in when and how women are getting pregnant. Demographers have in recent years described a “delayer boom,” in which birth rates have risen among the sort of women—college-educated—who tend to put off starting a family into their mid-30s or beyond. There are now more in this group than ever before: In 1980, just 12.8 percent of women had attained a bachelor’s degree or higher; by 2010, that number had almost tripled, to 37 percent. And women in their mid-30s have multiple births at a higher rate than younger women. A mother who is 35, for example, is four times more likely than a mother who is 20 to give birth to twins. That seems to be on account of her producing more follicle-stimulating hormone, or FSH, which boosts ovulation. The more FSH you have in your bloodstream, the greater your chances of producing more than one egg in each cycle, and having fraternal twins as a result.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

It turns out that creativity gets a boost from anger. While anger certainly is not beneficial in some contexts, researchers have found that angry people are more likely to be creative.

It turns out that creativity gets a boost from anger. While anger certainly is not beneficial in some contexts, researchers have found that angry people are more likely to be creative.

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

This counterintuitive idea was pursued by researchers Matthijs Baas, Carsten De Dreu, and Bernard Nijstad in a series of studies recently published in The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. They found that angry people were more likely to be creative – though this advantage didn’t last for long, as the taxing nature of anger eventually leveled out creativity. This study joins several recent lines of research exploring the relative upside to anger – the ways in which anger is not only less harmful than typically assumed, but may even be helpful (though perhaps in small doses).

In an initial study, the researchers found that feeling angry was indeed associated with brainstorming in a more unstructured manner, consistent with “creative” problem solving. In a second study, the researchers first elicited anger from the study participants (or sadness, or a non-emotional state) and then asked them to engage in a brainstorming session in which they generated ideas to preserve and improve the environment. In the beginning of this task, angry participants generated more ideas (by volume) and generated more original ideas (those thought of by less than 1 percent or less of the other participants), compared to the other sad or non-emotional participants. However, this benefit was only present in the beginning of the task, and eventually, the angry participants generated only as many ideas as the other participants.

These findings reported by Baas and colleagues make sense, given what we already know about anger. Though anger may be unpleasant to feel, it is associated with a variety of attributes that may facilitate creativity. First, anger is an energizing feeling, important for the sustained attention needed to solve problems creatively. Second, anger leads to more flexible, unstructured thought processes.

Anecdotal evidence from internal meetings at Apple certainly reinforces the notion that creativity may benefit from well-channeled anger. Apple is often cited as one of the wolrd’s most creative companies.

[div class=attrib]From Jonah Lehred over at Wired:[end-div]

Many of my favorite Steve Jobs stories feature his anger, as he unleashes his incisive temper on those who fail to meet his incredibly high standards. A few months ago, Adam Lashinsky had a fascinating article in Fortune describing life inside the sanctum of 1 Infinite Loop. The article begins with the following scene:

In the summer of 2008, when Apple launched the first version of its iPhone that worked on third-generation mobile networks, it also debuted MobileMe, an e-mail system that was supposed to provide the seamless synchronization features that corporate users love about their BlackBerry smartphones. MobileMe was a dud. Users complained about lost e-mails, and syncing was spotty at best. Though reviewers gushed over the new iPhone, they panned the MobileMe service.

Steve Jobs doesn’t tolerate duds. Shortly after the launch event, he summoned the MobileMe team, gathering them in the Town Hall auditorium in Building 4 of Apple’s campus, the venue the company uses for intimate product unveilings for journalists. According to a participant in the meeting, Jobs walked in, clad in his trademark black mock turtleneck and blue jeans, clasped his hands together, and asked a simple question:

“Can anyone tell me what MobileMe is supposed to do?” Having received a satisfactory answer, he continued, “So why the fuck doesn’t it do that?”

For the next half-hour Jobs berated the group. “You’ve tarnished Apple’s reputation,” he told them. “You should hate each other for having let each other down.” The public humiliation particularly infuriated Jobs. Walt Mossberg, the influential Wall Street Journal gadget columnist, had panned MobileMe. “Mossberg, our friend, is no longer writing good things about us,” Jobs said. On the spot, Jobs named a new executive to run the group.

Brutal, right? But those flashes of intolerant anger have always been an important part of Jobs’ management approach. He isn’t shy about the confrontation of failure and he doesn’t hold back negative feedback. He is blunt at all costs, a cultural habit that has permeated the company. Jonathan Ive, the lead designer at Apple, describes the tenor of group meetings as “brutally critical.”

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here and here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image of Brandy Norwood, courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Steve Jobs resigned from his position as Apple’s CEO, or chief executive officer, Wednesday. Taking his place is Tim Cook, previously the company’s COO, or chief operating officer. They also have a CFO, and, at one point or another, the company has had a CIO and CTO, too. When did we start calling corporate bosses C-this-O and C-that-O?

The 1970s. The phrase chief executive officer has been used, if at times rarely, in connection to corporate structures since at least the 19th century. (See, for instance, this 1888 book on banking law in Canada.) About 40 years ago, the phrase began gaining ground on president as the preferred title for the top director in charge of a company’s daily operations. Around the same time, the use of CEO in printed material surged and, if the Google Books database is to be believed, surpassed the long-form chief executive officer in the early 1980s. CFO has gained popularity, too, but at a much slower rate.

The online version of the Oxford English Dictionary published its first entries for CEO and CFO in January of this year. The entries’ first citations are a 1972 article in the Harvard Business Review and a 1971 Boston Globe article, respectively. (Niche publications were using the initials at least a half-decade earlier.) The New York Times seems to have printed its first CEO in a table graphic for a 1972 article, “Executives’ Pay Still Rising,” when space for the full phrase might have been lacking.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Thomas Rogers for Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Thomas Rogers for Slate:[end-div]

Over the last decade, American culture has been overtaken by a curious, overwhelming sense of nostalgia. Everywhere you look, there seems to be some new form of revivalism going on. The charts are dominated by old-school-sounding acts like Adele and Mumford & Sons. The summer concert schedule is dominated by reunion tours. TV shows like VH1’s “I Love the 90s” allow us to endlessly rehash the catchphrases of the recent past. And, thanks to YouTube and iTunes, new forms of music and pop culture are facing increasing competition from the ever-more-accessible catalog of older acts.

In his terrific new book, “Retromania,” music writer Simon Reynolds looks at how this nostalgia obsession is playing itself out everywhere from fashion to performance art to electronic music — and comes away with a worrying prognosis. If we continue looking backward, he argues, we’ll never have transformative decades, like the 1960s, or bold movements like rock ‘n’ roll, again. If all we watch and listen to are things that we’ve seen and heard before, and revive trends that have already existed, culture becomes an inescapable feedback loop.

Salon spoke to Reynolds over the phone from Los Angeles about the importance of the 1960s, the strangeness of Mumford & Sons — and why our future could be defined by boredom.

In the book you argue that our culture has increasingly been obsessed with looking backward, and that’s a bad thing. What makes you say that?

Every day, some new snippet of news comes along that is somehow connected to reconsuming the past. Just the other day I read that the famous Redding Festival in Britain is going to be screening a 1992 Nirvana concert during their festival. These events are like cultural antimatter. They won’t be remembered 20 years from now, and the more of them there are, the more alarming it is. I can understand why people want to go to them — they’re attractive and comforting. But this nostalgia seems to have crept into everything. The other day my daughter, who is 5 years old, was at camp, and they had an ’80s day. How can my daughter even understand what that means? She said the counselors were dressed really weird.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Slate.[end-div]

Ask a hundred people how science can be used for the good and you’re likely to get a hundred different answers. Well, Edge Magazine did just that, posing the question: “What scientific concept would improve everybody’s cognitive toolkit”, to 159 critical thinkers. Below we excerpt some of our favorites. The thoroughly engrossing, novel length article can be found here in its entirety.

[div class=attrib]From Edge:[end-div]

ether

Richard H. Thaler. Father of behavioral economics.

I recently posted a question in this space asking people to name their favorite example of a wrong scientific belief. One of my favorite answers came from Clay Shirky. Here is an excerpt:

The existence of ether, the medium through which light (was thought to) travel. It was believed to be true by analogy — waves propagate through water, and sound waves propagate through air, so light must propagate through X, and the name of this particular X was ether.

It’s also my favorite because it illustrates how hard it is to accumulate evidence for deciding something doesn’t exist. Ether was both required by 19th century theories and undetectable by 19th century apparatus, so it accumulated a raft of negative characteristics: it was odorless, colorless, inert, and so on.

Ecology

Brian Eno. Artist; Composer; Recording Producer: U2, Cold Play, Talking Heads, Paul Simon.

That idea, or bundle of ideas, seems to me the most important revolution in general thinking in the last 150 years. It has given us a whole new sense of who we are, where we fit, and how things work. It has made commonplace and intuitive a type of perception that used to be the province of mystics — the sense of wholeness and interconnectedness.

Beginning with Copernicus, our picture of a semi-divine humankind perfectly located at the centre of The Universe began to falter: we discovered that we live on a small planet circling a medium sized star at the edge of an average galaxy. And then, following Darwin, we stopped being able to locate ourselves at the centre of life. Darwin gave us a matrix upon which we could locate life in all its forms: and the shocking news was that we weren’t at the centre of that either — just another species in the innumerable panoply of species, inseparably woven into the whole fabric (and not an indispensable part of it either). We have been cut down to size, but at the same time we have discovered ourselves to be part of the most unimaginably vast and beautiful drama called Life.

We Are Not Alone In The Universe

J. Craig Venter. Leading scientist of the 21st century.

I cannot imagine any single discovery that would have more impact on humanity than the discovery of life outside of our solar system. There is a human-centric, Earth-centric view of life that permeates most cultural and societal thinking. Finding that there are multiple, perhaps millions of origins of life and that life is ubiquitous throughout the universe will profoundly affect every human.

Correlation is not a cause

Susan Blackmore. Psychologist; Author, Consciousness: An Introduction.

The phrase “correlation is not a cause” (CINAC) may be familiar to every scientist but has not found its way into everyday language, even though critical thinking and scientific understanding would improve if more people had this simple reminder in their mental toolkit.

One reason for this lack is that CINAC can be surprisingly difficult to grasp. I learned just how difficult when teaching experimental design to nurses, physiotherapists and other assorted groups. They usually understood my favourite example: imagine you are watching at a railway station. More and more people arrive until the platform is crowded, and then — hey presto — along comes a train. Did the people cause the train to arrive (A causes B)? Did the train cause the people to arrive (B causes A)? No, they both depended on a railway timetable (C caused both A and B).

A Statistically Significant Difference in Understanding the Scientific Process

Diane F. Halpern. Professor, Claremont McKenna College; Past-president, American Psychological Society.

Statistically significant difference — It is a simple phrase that is essential to science and that has become common parlance among educated adults. These three words convey a basic understanding of the scientific process, random events, and the laws of probability. The term appears almost everywhere that research is discussed — in newspaper articles, advertisements for “miracle” diets, research publications, and student laboratory reports, to name just a few of the many diverse contexts where the term is used. It is a short hand abstraction for a sequence of events that includes an experiment (or other research design), the specification of a null and alternative hypothesis, (numerical) data collection, statistical analysis, and the probability of an unlikely outcome. That is a lot of science conveyed in a few words.

Confabulation

Fiery Cushman. Post-doctoral fellow, Mind/Brain/Behavior Interfaculty Initiative, Harvard University.

We are shockingly ignorant of the causes of our own behavior. The explanations that we provide are sometimes wholly fabricated, and certainly never complete. Yet, that is not how it feels. Instead it feels like we know exactly what we’re doing and why. This is confabulation: Guessing at plausible explanations for our behavior, and then regarding those guesses as introspective certainties. Every year psychologists use dramatic examples to entertain their undergraduate audiences. Confabulation is funny, but there is a serious side, too. Understanding it can help us act better and think better in everyday life.

We are Lost in Thought

Sam Harris. Neuroscientist; Chairman, The Reason Project; Author, Letter to a Christian Nation.

I invite you to pay attention to anything — the sight of this text, the sensation of breathing, the feeling of your body resting against your chair — for a mere sixty seconds without getting distracted by discursive thought. It sounds simple enough: Just pay attention. The truth, however, is that you will find the task impossible. If the lives of your children depended on it, you could not focus on anything — even the feeling of a knife at your throat — for more than a few seconds, before your awareness would be submerged again by the flow of thought. This forced plunge into unreality is a problem. In fact, it is the problem from which every other problem in human life appears to be made.

I am by no means denying the importance of thinking. Linguistic thought is indispensable to us. It is the basis for planning, explicit learning, moral reasoning, and many other capacities that make us human. Thinking is the substance of every social relationship and cultural institution we have. It is also the foundation of science. But our habitual identification with the flow of thought — that is, our failure to recognize thoughts as thoughts, as transient appearances in consciousness — is a primary source of human suffering and confusion.

Knowledge

Mark Pagel. Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Reading University, England and The Santa Fe.

The Oracle of Delphi famously pronounced Socrates to be “the most intelligent man in the world because he knew that he knew nothing”. Over 2000 years later the physicist-turned-historian Jacob Bronowski would emphasize — in the last episode of his landmark 1970s television series the “Ascent of Man” — the danger of our all-too-human conceit of thinking we know something. What Socrates knew and what Bronowski had come to appreciate is that knowledge — true knowledge — is difficult, maybe even impossible, to come buy, it is prone to misunderstanding and counterfactuals, and most importantly it can never be acquired with exact precision, there will always be some element of doubt about anything we come to “know”‘ from our observations of the world.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

Advertisers have long known how to pull at our fickle emotions and inner motivations to sell their products. Further still many corporations fine-tune their products to the nth degree to ensure we learn to crave more of the same. Whether it’s the comforting feel of an armchair, the soft yet lingering texture of yogurt, the fresh scent of hand soap, or the crunchiness of the perfect potato chip, myriad focus groups, industrial designers and food scientists are hard at work engineering our addictions.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

Feeling low? According to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research, when people feel bad, their sense of touch quickens and they instinctively want to hug something or someone. Tykes cling to a teddy bear or blanket. It’s a mammal thing. If young mammals feel gloomy, it’s usually because they’re hurt, sick, cold, scared or lost. So their brain rewards them with a gust of pleasure if they scamper back to mom for a warm nuzzle and a meal. No need to think it over. All they know is that, when a negative mood hits, a cuddle just feels right; and if they’re upbeat and alert, then their eyes hunger for new sights and they’re itching to explore.

It’s part of evolution’s gold standard, the old carrot-and-stick gambit, an impulse that evades reflection because it evolved to help infants thrive by telling them what to do — not in words but in sequins of taste, heartwarming touches, piquant smells, luscious colors.

Back in the days before our kind knew what berries to eat, let alone which merlot to choose or HD-TV to buy, the question naturally arose: How do you teach a reckless animal to live smart? Some brains endorsed correct, lifesaving behavior by doling out sensory rewards. Healthy food just tasted yummy, which is why we now crave the sweet, salty, fatty foods our ancestors did — except that for them such essentials were rare, needing to be painstakingly gathered or hunted. The seasoned hedonists lived to explore and nuzzle another day — long enough to pass along their snuggly, junk-food-bedeviled genes.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Children are not what they used to be. They tweet and blog and text without batting an eyelash. Whenever they need the answer to a question, they simply log onto their phone and look it up on Google. They live in a state of perpetual, endless distraction, and, for many parents and educators, it’s a source of real concern. Will future generations be able to finish a whole book? Will they be able to sit through an entire movie without checking their phones? Are we raising a generation of impatient brats?

According to Cathy N. Davidson, a professor of interdisciplinary studies at Duke University, and the author of the new book “Now You See It: How Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn,” much of the panic about children’s shortened attention spans isn’t just misguided, it’s harmful. Younger generations, she argues, don’t just think about technology more casually, they’re actually wired to respond to it in a different manner than we are, and it’s up to us — and our education system — to catch up to them.

Davidson is personally invested in finding a solution to the problem. As vice provost at Duke, she spearheaded a project to hand out a free iPod to every member of the incoming class, and began using wikis and blogs as part of her teaching. In a move that garnered national media attention, she crowd-sourced the grading in her course. In her book, she explains how everything from video gaming to redesigned schools can enhance our children’s education — and ultimately, our future.

Salon spoke to Davidson over the phone about the structure of our brains, the danger of multiple-choice testing, and what the workplace of the future will actually look like.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

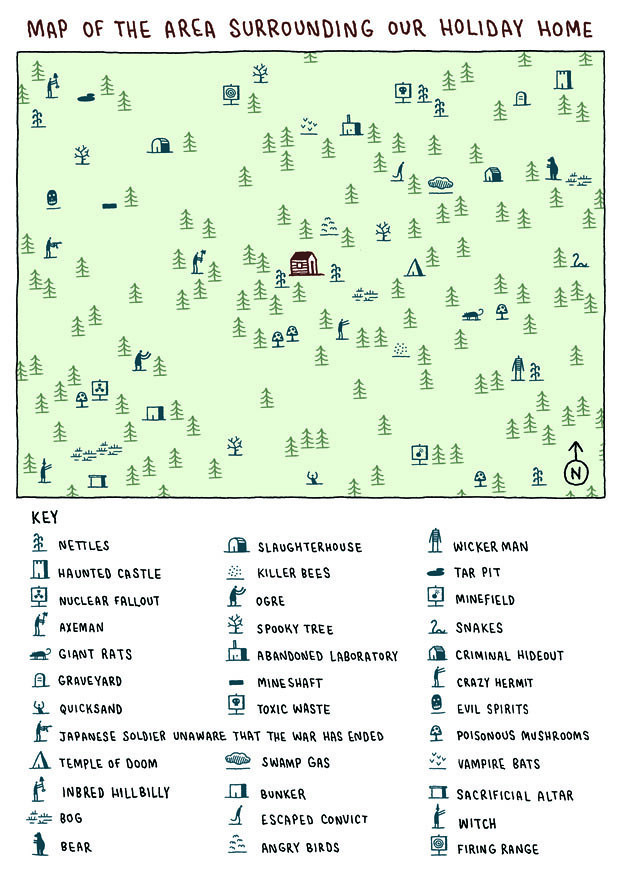

Not quite as poetic and intricate as Dante’s circuitous map of hell but a fascinating invention by Tom Gauld nonetheless.

[div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs for Strange Maps:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs for Strange Maps:[end-div]

“A perpetual holiday is a good working definition of hell”, said George Bernard Shaw; in fact, just the odd few weeks of summer vacation may be near enough unbearable – what with all the frantic packing and driving, the getting lost and having forgotten, the primitive lodgings, lousy food and miserable weather, not to mention the risk of disease and unfriendly natives.

And yet, even for the bored teenagers forced to join their parents’ on their annual work detox, the horrors of the summer holiday mix with the chance of thrilling adventures, beckoning beyond the unfamiliar horizon.

Tom Gauld may well have been such a teenager, for this cartoon of his deftly expresses both the eeriness and the allure of obligatory relaxation in a less than opportune location. It evokes both the ennui of being where you don’t want to be, and the exhilarating exotism of those surroundings – as if they were an endpaper map of a Boys’ Own adventure, waiting for the dotted line of your very own expedition.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

The world of science is replete with nouns derived from people. There is the Amp (named after André-Marie Ampère); the Volt (after Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta), the Watt (after the Scottish engineer James Watt). And the list goes on. We have the Kelvin, Ohm, Coulomb, Celsius, Hertz, Joule, Sievert. We also have more commonly used nouns in circulation that derive from people. The mackintosh, cardigan and sandwich are perhaps the most frequently used.

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Before there were silhouettes, there was a French fellow named Silhouette. And before there were Jacuzzi parties there were seven inventive brothers by that name. It’s easy to forget that some of the most common words in the English language came from living, breathing people. Explore these real-life namesakes courtesy of Slate’s partnership with LIFE.com.

Jules Leotard: Tight Fit

French acrobat Jules Leotard didn’t just invent the art of the trapeze, he also lent his name to the skin-tight, one-piece outfit that allowed him to keep his limbs free while performing.

It would be fascinating to see if today’s popular culture might lend surnames with equal staying power to our language.

[div class=attrib]Slate has some more fascinating examples, here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, 1783, by Thomas Gainsborough. Courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

Why do some words take hold in the public consciousness and persist through generations while others fall by the wayside after one season?

Why do some words take hold in the public consciousness and persist through generations while others fall by the wayside after one season?

Despite the fleetingness of many new slang terms, such as txtnesia (“when you forget what you texted someone last”), a visit to the Urbandictionary will undoubtedly amuse at the inventiveness of our our language., though gobsmacked and codswallop may come to mind as well.

[div class=attrib]From State:[end-div]

Feeling nostalgic for a journalistic era I never experienced, I recently read Tom Wolfe’s 1968 The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. I’d been warned that the New Journalists slathered their prose with slang, so I wasn’t shocked to find nonstandard English on nearly every line: dig, trippy, groovy, grok, heads, hip, mysto and, of course, cool. This psychedelic time capsule led me to wonder about the relative stickiness of all these words—the omnipresence of cool versus the datedness of groovy and the dweeb cachet of grok, a Robert Heinlein coinage from Stranger in a Strange Land literally signifying to drink but implying profound understanding. Mysto, an abbreviation for mystical, seems to have fallen into disuse. It doesn’t even have an Urban Dictionary entry.

There’s no grand unified theory for why some slang terms live and others die. In fact, it’s even worse than that: The very definition of slang is tenuous and clunky. Writing for the journal American Speech, Bethany Dumas and Jonathan Lighter argued in 1978 that slang must meet at least two of the following criteria: It lowers “the dignity of formal or serious speech or writing,” it implies that the user is savvy (he knows what the word means, and knows people who know what it means), it sounds taboo in ordinary discourse (as in with adults or your superiors), and it replaces a conventional synonym. This characterization seems to open the door to words that most would not recognize as slang, including like in the quotative sense: “I was like … and he was like.” It replaces a conventional synonym (said), and certainly lowers seriousness, but is probably better categorized as a tic.

At least it’s widely agreed that young people, seeking to make a mark, are especially prone to generating such dignity-reducing terms. (The editor of The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, Tom Dalzell, told me that “every generation comes up with a new word for a marijuana cigarette.”) Oppressed people, criminals, and sports fans make significant contributions, too. There’s also a consensus that most slang, like mysto, is ephemeral. Connie Eble, a linguist at the University of North Carolina, has been collecting slang from her students since the early 1970s. (She asks them to write down terms heard around campus.) In 1996, when she reviewed all the submissions she’d received, she found that more than half were only turned in once. While many words made it from one year to the next, only a tiny minority lasted a decade.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Slate.[end-div]

Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope.

Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope.

[div class=attrib]Alexander Edmonds for the New York Times:[end-div]

While living in Rio de Janeiro in 1999, I saw something that caught my attention: a television broadcast of a Carnival parade that paid homage to a plastic surgeon, Dr. Ivo Pitanguy. The doctor led the procession surrounded by samba dancers in feathers and bikinis. Over a thundering drum section and anarchic screech of a cuica, the singer praised Pitanguy for “awakening the self-esteem in each ego” with a “scalpel guided by heaven.”

It was the height of Rio’s sticky summer and the city had almost slowed to a standstill, as had progress on my anthropology doctorate research on Afro-Brazilian syncretism. After seeing the parade, I began to notice that Rio’s plastic surgery clinics were almost as numerous as beauty parlors (and there are a lot of those). Newsstands sold magazines with titles like Plástica & Beauty, next to Marie Claire. I assumed that the popularity of cosmetic surgery in a developing nation was one more example of Brazil’s gaping inequalities. But Pitanguy had long maintained that plastic surgery was not only for the rich: “The poor have the right to be beautiful, too,” he has said.

The beauty of the human body has raised distinct ethical issues for different epochs. The literary scholar Elaine Scarry pointed out that in the classical world a glimpse of a beautiful person could imperil an observer. In his “Phaedrus” Plato describes a man who after beholding a beautiful youth begins to spin, shudder, shiver and sweat. With the rise of mass consumption, ethical discussions have focused on images of female beauty. Beauty ideals are blamed for eating disorders and body alienation. But Pitanguy’s remark raises yet another issue: Is beauty a right, which, like education or health care, should be realized with the help of public institutions and expertise?

The question might seem absurd. Pitanguy’s talk of rights echoes the slogans of make-up marketing (L’Oreal’s “Because you’re worth it.”). Yet his vision of plastic surgery reflects a clinical reality that he helped create. For years he has performed charity surgeries for the poor. More radically, some of his students offer free cosmetic operations in the nation’s public health system.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Neuroanthropology:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Neuroanthropology:[end-div]

The most recent edition of Behavioral and Brain Sciences carries a remarkable review article by Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan, ‘The weirdest people in the world?’ The article outlines two central propositions; first, that most behavioural science theory is built upon research that examines intensely a narrow sample of human variation (disproportionately US university undergraduates who are, as the authors write, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, or ‘WEIRD’).

More controversially, the authors go on to argue that, where there is robust cross-cultural research, WEIRD subjects tend to be outliers on a range of measurable traits that do vary, including visual perception, sense of fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, and a host of other basic psychological traits. They don’t ignore universals – discussing them in several places – but they do highlight human variation and its implications for psychological theory.

As is the custom at BBS, the target article is accompanied by a large number of responses from scholars around the world, and then a synthetic reflection from the original target article authors to the many responses (in this case, 28). The total of the discussion weighs in at a hefty 75 pages, so it will take most readers (like me) a couple of days to digest the whole thing.

t’s my second time encountering the article as I read a pre-print version and contemplated proposing a response, but, sadly, there was just too much I wanted to say, and not enough time in the calendar (conference organizing and the like dominating my life) for me to be able to pull it together. I regret not writing a rejoinder, but I can do so here with no limit on my space and the added advantage of seeing how other scholars responded to the article.

My one word review of the collection of target article and responses: AMEN!

Or maybe that should be, AAAAAAAMEEEEEN! {Sung by angelic voices.}

There’s a short version of the argument in Nature as well, but the longer version is well worth the read.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

Scents are deeply evokative. A faint whiff of a distinct and rare scent can bring back a long forgotten memory and make it vivid, and do so like no other sense. Smells can make our stomachs churn and make us swoon.

Scents are deeply evokative. A faint whiff of a distinct and rare scent can bring back a long forgotten memory and make it vivid, and do so like no other sense. Smells can make our stomachs churn and make us swoon.

The scent-making industry has been with us for thousands of years. In 2005, archeologists discovered the remains of a perfume factory on the island of Cyprus dating back over 4,000 years. So, it’s no surprise that makers of fragrances, from artificial aromas for foods to complex nasal “notes” for perfumes and deodorants, now comprise a multi-billion dollar global industry. Krystal D’Costa over at Anthropology in Practice takes us on a fine aromatic tour, and concludes her article with a view to which most can surely relate:

My perfume definitely makes me feel better. It wraps me in a protective cocoon that prepares me to face just about any situation. Hopefully, when others encounter a trace of it, they think of me in my most confident and warmest form.

A related article in the Independent describes how an increasing number of retailers are experimenting with scents to entice shoppers to linger and spend more time and money in their stores. We learn that

. . . a study run by Nike showed that adding scents to their stores increased intent to purchase by 80 per cent, while in another experiment at a petrol station with a mini-mart attached to it, pumping around the smell of coffee saw purchases of the drink increase by 300 per cent.

[div class=attrib]More from Anthropology in Practice:[end-div]

At seventeen I discovered the perfume that would become my signature scent. It’s a warm, rich, inviting fragrance that reminds me (and hopefully others) of a rose garden in full bloom. Despite this fullness, it’s light enough to wear all day and it’s been in the background of many of my life experiences. It announces me: the trace that lingers in my wake leaves a subtle reminder of my presence. And I can’t deny that it makes me feel a certain way: as though I could conquer the world. (Perhaps one day, when I do conquer the world, that will be the quirk my biographers note: that I had a bottle of X in my bag at all times.)

Our world is awash in smells—everything has an odor. Some are pleasant, like flowers or baked goods, and some are unpleasant, like exhaust fumes or sweaty socks—and they’re all a subjective experience: The odors that one person finds intoxicating may not have the same effect on another. (Hermione Granger’s fondness for toothpaste is fantastic example of the personal relationship we can have with the smells that permeate our world.) Nonetheless, they constitute a very important part of our experiences. We use them to make judgments about our environments (and each other), they can trigger memories, and even influence behaviors.

No odors seem to concern us more than our own, however. But you don’t have to take my word for it—the numbers speak for themselves: In 2010, people around the world spent the equivalent of $2.2 billion USD on fragrances, making the sale of essential oils and aroma chemicals a booming business. The history of aromatics sketches our attempts to control and manipulate scents— socially and chemically—illustrating how we’ve carefully constructed the smells in our lives.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: The Perfume Maker by Ernst, Rodolphe, courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom?

A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom?

[div class=attrib]From the Splintered Mind:[end-div]

When I gaze into a mirror, does it look like there’s someone a few feet away gazing back at me? (Someone who looks a lot like me, though perhaps a bit older and grumpier.) Or does it look like I’m standing where I in fact am, in the middle of the bathroom? Or does it somehow look both ways? Suppose my son is sneaking up behind me and I see him in the same mirror. Does it look like he is seven feet in front of me, sneaking up behind the dope in the mirror and I only infer that he is actually behind me? Or does he simply look, instead, one foot behind me?

Suppose I’m in a new restaurant and it takes me a moment to notice that one wall is a mirror. Surely, before I notice, the table that I’m looking at in the mirror appears to me to be in a location other than its real location. Right? Now, after I notice that it’s a mirror, does the table look to be in a different place than it looked to be a moment ago? I’m inclined to say that in the dominant sense of “apparent location”, the apparent location of the table is just the same, but now I’m wise to it and I know its apparent location isn’t its real location. On the other hand, though, when I look in the rear-view mirror in my car I want to say that it looks like that Mazda is coming up fast behind me, not that it looks like there is a Mazda up in space somewhere in front of me.

What is the difference between these cases that makes me want to treat them differently? Does it have to do with familiarity and skill? I guess that’s what I’m tempted to say. But then it seems to follow that, with enough skill, things will look veridical through all kinds of reflections, refractions, and distortions. Does the oar angling into water really look straight to the skilled punter? With enough skill, could even the image in a carnival mirror look perfectly veridical? Part of me wants to resist at least that last thought, but I’m not sure how to do so and still say all the other things I want to say.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Adrian Pingstone, Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

A recent study by Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London places the seat of our sense of beauty in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC). Not very romantic of course, but thoroughly reasonable that this compound emotion would be found in an area of the brain linked with reward and pleasure.

[div class=attrib]The results are described over at Not Exactly Rocket Science / Discover:[end-div]

Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London watched the brains of 21 volunteers as they looked at 30 paintings and listened to 30 musical excerpts. All the while, they were lying inside an fMRI scanner, a machine that measures blood flow to different parts of the brain and shows which are most active. The recruits rated each piece as “beautiful”, “indifferent” or “ugly”.

The scans showed that one part of their brains lit up more strongly when they experienced beautiful images or music than when they experienced ugly or indifferent ones – the medial orbitofrontal cortex or mOFC.

Several studies have linked the mOFC to beauty, but this is a sizeable part of the brain with many roles. It’s also involved in our emotions, our feelings of reward and pleasure, and our ability to make decisions. Nonetheless, Ishizu and Zeki found that one specific area, which they call “field A1” consistently lit up when people experienced beauty.

The images and music were accompanied by changes in other parts of the brain as well, but only the mOFC reacted to beauty in both forms. And the more beautiful the volunteers found their experiences, the more active their mOFCs were. That is not to say that the buzz of neurons in this area produces feelings of beauty; merely that the two go hand-in-hand.

Clearly, this is a great start, and as brain scientists get their hands on ever improving fMRI technology and other brain science tools our understanding will only get sharper. However, what still remains very much a puzzle is “why does our sense of beauty exist”?

The researchers go on to explain their results, albeit tentatively:

Our proposal shifts the definition of beauty very much in favour of the perceiving subject and away from the characteristics of the apprehended object. Our definition… is also indifferent to what is art and what is not art. Almost anything can be considered to be art, but only creations whose experience has, as a correlate, activity in mOFC would fall into the classification of beautiful art… A painting by Francis Bacon may be executed in a painterly style and have great artistic merit but may not qualify as beautiful to a subject, because the experience of viewing it does not correlate with activity in his or her mOFC.

In proposing this the researchers certainly seem to have hit on the underlying “how” of beauty, and it’s reliably consistent, though the sample was not large enough to warrant statistical significance. However, the researchers conclude that “A beautiful thing is met with the same neural changes in the brain of a wealthy cultured connoisseur as in the brain of a poor, uneducated novice, as long as both of them find it beautiful.”

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But why does beauty exist? What’s the point of marveling at a Rembrandt self portrait or a Bach fugue? To paraphrase Auden, beauty makes nothing happen. Unlike our more primal indulgences, the pleasure of perceiving beauty doesn’t ensure that we consume calories or procreate. Rather, the only thing beauty guarantees is that we’ll stare for too long at some lovely looking thing. Museums are not exactly adaptive.

The answer to this question has stumped the research community for quite some time, and will undoubtedly continue to do so for some time to come. Several recent cognitive research studies hint at possible answers related to reinforcement for curious and inquisitive behavior, reward for and feedback from anticipation responses, and pattern seeking behavior.

[div class=attrib]More from Jonah Lehrer for Wired:[end-div]

What I like about this speculation is that it begins to explain why the feeling of beauty is useful. The aesthetic emotion might have begun as a cognitive signal telling us to keep on looking, because there is a pattern here that we can figure out it. In other words, it’s a sort of a metacognitive hunch, a response to complexity that isn’t incomprehensible. Although we can’t quite decipher this sensation – and it doesn’t matter if the sensation is a painting or a symphony – the beauty keeps us from looking away, tickling those dopaminergic neurons and dorsal hairs. Like curiosity, beauty is a motivational force, an emotional reaction not to the perfect or the complete, but to the imperfect and incomplete. We know just enough to know that we want to know more; there is something here, we just don’t what. That’s why we call it beautiful.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Claude Monet, Water-Lily Pond and Weeping Willow. Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]First page of the manuscript of Bach’s lute suite in G Minor. Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From TreeHugger:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From TreeHugger:[end-div]

Aristotle said “No great genius was without a mixture of insanity.” Marcel Proust wrote “Everything great in the world is created by neurotics. They have composed our masterpieces, but we don’t consider what they have cost their creators in sleepless nights, and worst of all, fear of death.”

Perhaps that’s why Jakub Szcz?sny designed this hermitage, this “studio for invited guests – young creators and intellectualists from all over the world.”- it will drive them completely crazy.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the idea of living in small spaces. I write about them all the time. But the Keret House is 122 cm (48.031″) at its widest, 72 (28.34″) at its narrowest. I know people wider than that.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

Technology continues to march on, though some would argue that it may not necessarily be a march forward. Technology is indifferent to romance and historic precedent, and so the lowly postcard finds itself increasing under threat from Flickr and Twitter and smartphones and Instagram and Facebook.

[div class=attrib]Charles Simic laments over at the New York Review of Books:[end-div]

Here it is already August and I have received only one postcard this summer. It was sent to me by a European friend who was traveling in Mongolia (as far as I could deduce from the postage stamp) and who simply sent me his greetings and signed his name. The picture in color on the other side was of a desert broken up by some parched hills without any hint of vegetation or sign of life, the name of the place in characters I could not read. Even receiving such an enigmatic card pleased me immensely. This piece of snail mail, I thought, left at the reception desk of a hotel, dropped in a mailbox, or taken to the local post office, made its unknown and most likely arduous journey by truck, train, camel, donkey—or whatever it was— and finally by plane to where I live.

Until a few years ago, hardly a day would go by in the summer without the mailman bringing a postcard from a vacationing friend or acquaintance. Nowadays, you’re bound to get an email enclosing a photograph, or, if your grandchildren are the ones doing the traveling, a brief message telling you that their flight has been delayed or that they have arrived. The terrific thing about postcards was their immense variety. It wasn’t just the Eiffel Tower or the Taj Mahal, or some other famous tourist attraction you were likely to receive in the mail, but also a card with a picture of a roadside diner in Iowa, the biggest hog at some state fair in the South, and even a funeral parlor touting the professional excellence that their customers have come to expect over a hundred years. Almost every business in this country, from a dog photographer to a fancy resort and spa, had a card. In my experience, people in the habit of sending cards could be divided into those who go for the conventional images of famous places and those who delight in sending images whose bad taste guarantees a shock or a laugh.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image of Aloha Nui Postcard of Luakaha, Home of C.M. Cooke, courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class attrib]From Wilson Quarterly:[end-div]

[div class attrib]From Wilson Quarterly:[end-div]

For all its stellar achievements, human reason seems particularly ill suited to, well, reasoning. Study after study demonstrates reason’s deficiencies, such as the oft-noted confirmation bias (the tendency to recall, select, or interpret evidence in a way that supports one’s preexisting beliefs) and people’s poor performance on straightforward logic puzzles. Why is reason so defective?

To the contrary, reason isn’t defective in the least, argue cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier of the University of Pennsylvania and Dan Sperber of the Jean Nicod Institute in Paris. The problem is that we’ve misunderstood why reason exists and measured its strengths and weaknesses against the wrong standards.

Mercier and Sperber argue that reason did not evolve to allow individuals to think through problems and make brilliant decisions on their own. Rather, it serves a fundamentally social purpose: It promotes argument. Research shows that people solve problems more effectively when they debate them in groups—and the interchange also allows people to hone essential social skills. Supposed defects such as the confirmation bias are well fitted to this purpose because they enable people to efficiently marshal the evidence they need in arguing with others.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

WHEN David Hilbert left the podium at the Sorbonne in Paris, France, on 8 August 1900, few of the assembled delegates seemed overly impressed. According to one contemporary report, the discussion following his address to the second International Congress of Mathematicians was “rather desultory”. Passions seem to have been more inflamed by a subsequent debate on whether Esperanto should be adopted as mathematics’ working language.

Yet Hilbert’s address set the mathematical agenda for the 20th century. It crystallised into a list of 23 crucial unanswered questions, including how to pack spheres to make best use of the available space, and whether the Riemann hypothesis, which concerns how the prime numbers are distributed, is true.

Today many of these problems have been resolved, sphere-packing among them. Others, such as the Riemann hypothesis, have seen little or no progress. But the first item on Hilbert’s list stands out for the sheer oddness of the answer supplied by generations of mathematicians since: that mathematics is simply not equipped to provide an answer.

This curiously intractable riddle is known as the continuum hypothesis, and it concerns that most enigmatic quantity, infinity. Now, 140 years after the problem was formulated, a respected US mathematician believes he has cracked it. What’s more, he claims to have arrived at the solution not by using mathematics as we know it, but by building a new, radically stronger logical structure: a structure he dubs “ultimate L”.

The journey to this point began in the early 1870s, when the German Georg Cantor was laying the foundations of set theory. Set theory deals with the counting and manipulation of collections of objects, and provides the crucial logical underpinnings of mathematics: because numbers can be associated with the size of sets, the rules for manipulating sets also determine the logic of arithmetic and everything that builds on it.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]