If you’re an atheist, like me, you will certainly relate to the excerpted interviews below — where each individual “unbeliever” recounts her or his views on living a purposeful life in an thoroughly indifferent, meaningless and beautiful universe. If you’re a “non-unbeliever”, you will see that meaning is all around.

As writer Gia Milinovich puts it:

It is enough that I exist, that I am here now, albeit briefly, with all of you. And it’s an amazing, astonishing, remarkable, totally mind-blowing fucking miracle.

From Buzzfeed:

Jerry Coyne, evolutionary biologist:

“The way I find meaning is the way that most people find meaning, even religious ones, which is to get pleasure and significance from your job, from your loved ones, from your avocation, art, literature, music. People like me don’t worry about what it’s all about in a cosmic sense, because we know it isn’t about anything. It’s what we make of this transitory existence that matters.

“If you’re an atheist and an evolutionary biologist, what you think is, I’m lucky to have these 80-odd years: How can I make the most of my existence here? Being an atheist means coming to grips with reality. And the reality is twofold. We’re going to die as individuals, and the whole of humanity, unless we find a way to colonise other planets, is going to go extinct. So there’s lots of things that we have to deal with that we don’t like. We just come to grips with the reality. Life is the result of natural selection, and death is the result of natural selection. We are evolved in such a way that death is almost inevitable. So you just deal with it.

“It says in the Bible that, ‘When I was a child I played with childish things, and when I became a man I put away those childish things.’ And one of those childish things is the superstition that there’s a higher purpose. Christopher Hitchens said it’s time to move beyond the mewling childhood of our species and deal with reality as it is, and that’s what we have to do.”

Susan Blackmore, psychologist:

“If I get a what’s-it-all-for sort of feeling, then I say to myself, What’s the point of it all? There isn’t any point. And somehow, for me – I know it’s not true for other people – that is really comforting. It slows me down. It reminds me that I didn’t ask to be born here, I’ll be gone, and I won’t know what’ll happen, I’ll just be gone, so get on with it. I find that comforting, to say to myself that there is no point, I live in a pointless universe. Here I am, for better or worse, get on with it.

“I was thinking about this yesterday. I was gardening, out there pulling up brambles, and I thought, Why do I do this? And the answer is, because I’m smiling, I’m enjoying it, and actually I love it. It’s because of the cycles of life. I was thinking, What’s the point of growing these beans again, because they’ll just die, and then next year I’ll do the same thing again. But isn’t that a great pleasure in life, that that’s how it is? The beans come and go, and you eat them and they die, and you do the work, and you see it come and go. Today is the due date for my first grandchild, and I think similarly about that. The cycles of birth and death. Here I am in the autumn of my life, I suppose – I’m 64 – and I’m just going through the same cycles that everyone goes through, and it gives me a sense of connection with other people. God, that sounds a bit poncey.

“The pointlessness of life is not a thing to be overcome. It’s something to be celebrated now, because that’s all there is.”

…

Kat Arney, biologist and science writer:

“I was raised in the Church of England. As a teenager, I ‘found Jesus’ and joined the evangelical movement, probably because I desperately wanted to feel part of a group, and also loved playing in the church band. I finally had my reverse Damascene moment as a post-doctoral researcher, desperately unhappy with my scientific career, relationship, and pretty much everything else, and can clearly remember the sudden realisation: I had one life, and I had to make the best of it. There was no heaven or hell, no magic man in the sky, and I was the sole captain of my ship.

“It was an incredibly liberating moment, and made me realise that the true meaning of life is what I make with the people around me – my family, friends, colleagues, and strangers. People tell religious fairy stories to create meaning, but I’d rather face up to what all the evidence suggests is the scientific truth – all we really have is our own humanity. So let’s be gentle to each other and share the joy of simply being alive, here and now. Let’s give it our best shot.”

Dr Buddhini Samarasinghe, molecular biologist:

“I think there are two things about living in a godless universe that scare some people. First, there is no one watching over them, benevolently guiding their lives. Second, because there is no life after death, it all feels rather bleak.

“Instead of scaring me, I find these two things incredibly liberating. It means that I am free to do as I want; my choices are truly mine. Furthermore, I feel determined to make the most of the years I have left on this planet, and not squander it. The life I live now is not a dress rehearsal for something greater afterwards; it empowers me to focus on the here and now. That is how I find meaning and purpose in what might seem a meaningless and purposeless existence; by concentrating on what I can do, and the differences I can make in the lives of those around me, in the short time that we have.”

Read the entire article here.

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,  theDiagonal has carried several recent articles (

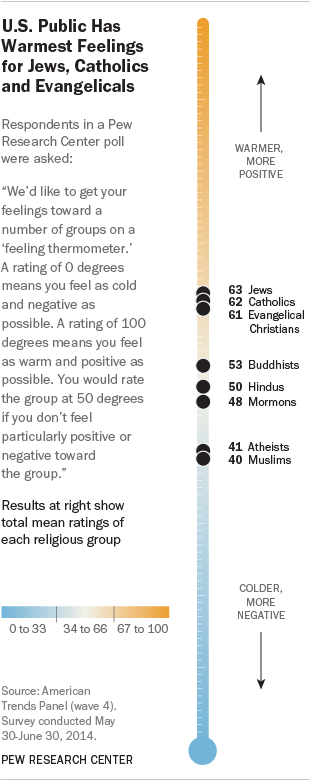

theDiagonal has carried several recent articles ( The social standing of atheists seems to be on the rise. Back in December we

The social standing of atheists seems to be on the rise. Back in December we  For adults living in North America, the answer is that it’s probably more likely that they would prefer a rapist teacher as babysitter over an atheistic one. Startling as that may seem, the conclusion is backed by some real science, excerpted below.

For adults living in North America, the answer is that it’s probably more likely that they would prefer a rapist teacher as babysitter over an atheistic one. Startling as that may seem, the conclusion is backed by some real science, excerpted below. [div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]