Albert Einstein famously called quantum entanglement “spooky action at a distance”. It refers to the notion that measuring the state of one of two entangled particles makes the state of the second particle known instantaneously, regardless of the distance separating the two particles. Entanglement seems to link these particles and make them behave as one system. This peculiar characteristic has been a core element of the counterintuitiive world of quantum theory. Yet while experiments have verified this spookiness, other theorists maintain that both theory and experiment are flawed, and that a different interpretation is required. However, one such competing theory — the many worlds interpretation — makes equally spooky predictions.

From ars technica:

Quantum nonlocality, perhaps one of the most mysterious features of quantum mechanics, may not be a real phenomenon. Or at least that’s what a new paper in the journal PNAS asserts. Its author claims that nonlocality is nothing more than an artifact of the Copenhagen interpretation, the most widely accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Nonlocality is a feature of quantum mechanics where particles are able to influence each other instantaneously regardless of the distance between them, an impossibility in classical physics. Counterintuitive as it may be, nonlocality is currently an accepted feature of the quantum world, apparently verified by many experiments. It’s achieved such wide acceptance that even if our understandings of quantum physics turn out to be completely wrong, physicists think some form of nonlocality would be a feature of whatever replaced it.

The term “nonlocality” comes from the fact that this “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein famously called it, seems to put an end to our intuitive ideas about location. Nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, so if two quantum particles can influence each other faster than light could travel between the two, then on some level, they act as a single system—there must be no real distance between them.

The concept of location is a bit strange in quantum mechanics anyway. Each particle is described by a mathematical quantity known as the “wave function.” The wave function describes a probability distribution for the particle’s location, but not a definite location. These probable locations are not just scientists’ guesses at the particle’s whereabouts; they’re actual, physical presences. That is to say, the particles exist in a swarm of locations at the same time, with some locations more probable than others.

A measurement collapses the wave function so that the particle is no longer spread out over a variety of locations. It begins to act just like objects we’re familiar with—existing in one specific location.

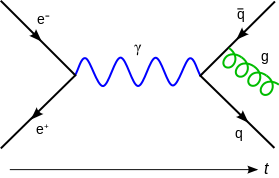

The experiments that would measure nonlocality, however, usually involve two particles that are entangled, which means that both are described by a shared wave function. The wave function doesn’t just deal with the particle’s location, but with other aspects of its state as well, such as the direction of the particle’s spin. So if scientists can measure the spin of one of the two entangled particles, the shared wave function collapses and the spins of both particles become certain. This happens regardless of the distance between the particles.

The new paper calls all this into question.

The paper’s sole author, Frank Tipler, argues that the reason previous studies apparently confirmed quantum nonlocality is that they were relying on an oversimplified understanding of quantum physics in which the quantum world and the macroscopic world we’re familiar with are treated as distinct from one another. Even large structures obey the laws of quantum Physics, Tipler points out, so the scientists making the measurements must be considered part of the system being studied.

It is intuitively easy to separate the quantum world from our everyday world, as they appear to behave so differently. However, the equations of quantum mechanics can be applied to large objects like human beings, and they essentially predict that you’ll behave just as classical physics—and as observation—says you will. (Physics students who have tried calculating their own wave functions can attest to this). The laws of quantum physics do govern the entire Universe, even if distinctly quantum effects are hard to notice at a macroscopic level.

When this is taken into account, according to Tipler, the results of familiar nonlocality experiments are altered. Typically, such experiments are thought to involve only two measurements: one on each of two entangled particles. But Tipler argues that in such experiments, there’s really a third measurement taking place when the scientists compare the results of the two.

This third measurement is crucial, Tipler argues, as without it, the first two measurements are essentially meaningless. Without comparing the first two, there’s no way to know that one particle’s behavior is actually linked to the other’s. And crucially, in order for the first two measurements to be compared, information must be exchanged between the particles, via the scientists, at a speed less than that of light. In other words, when the third measurement is taken into account, the two particles are not communicating faster than light. There is no “spooky action at a distance.”

Tipler has harsh criticism for the reasoning that led to nonlocality. “The standard argument that quantum phenomena are nonlocal goes like this,” he says in the paper. “(i) Let us add an unmotivated, inconsistent, unobservable, nonlocal process (collapse) to local quantum mechanics; (ii) note that the resulting theory is nonlocal; and (iii) conclude that quantum mechanics is [nonlocal].”

He’s essentially saying that scientists are arbitrarily adding nonlocality, which they can’t observe, and then claiming they have discovered nonlocality. Quite an accusation, especially for the science world. (The “collapse” he mentions is the collapse of the particle’s wave function, which he asserts is not a real phenomenon.) Instead, he claims that the experiments thought to confirm nonlocality are in fact confirming an alternative to the Copenhagen interpretation called the many-worlds interpretation (MWI). As its name implies, the MWI predicts the existence of other universes.

The Copenhagen interpretation has been summarized as “shut up and measure.” Even though the consequences of a wave function-based world don’t make much intuitive sense, it works. The MWI tries to keep particles concrete at the cost of making our world a bit fuzzy. It posits that rather than becoming a wave function, particles remain distinct objects but enter one of a number of alternative universes, which recombine to a single one when the particle is measured.

Scientists who thought they were measuring nonlocality, Tipler claims, were in fact observing the effects of alternate universe versions of themselves, also measuring the same particles.

Part of the significance of Tipler’s claim is that he’s able to mathematically derive the same experimental results from the MWI without use of nonlocality. But this does not necessarily make for evidence that the MWI is correct; either interpretation remains consistent with the data. Until the two can be distinguished experimentally, it all comes down to whether you personally like or dislike nonlocality.

Read the entire article here.

Oh, what a fruitful conversation;-)

Oh, what a fruitful conversation;-)