If you’ve ever owned vinyl — the circular, black, 12 inch kind — you will know that there are certain pleasures associated with it. The different quality of sound from the spiraling grooves; the (usually) gorgeous album cover art; the printed lyrics and liner notes, sometimes an included wall poster.

Cassette tapes and then CDs shrank these pleasures. Then came the death knell, tolled by MP3 (or MPEG3) and MP4 and finally streaming.

Fortunately some of us have managed to hold on to our precious vinyl collections: our classic LPs and rare 12-inch singles; though not so much the 45s. And, to some extent vinyl is having a small — but probably temporary — renaissance.

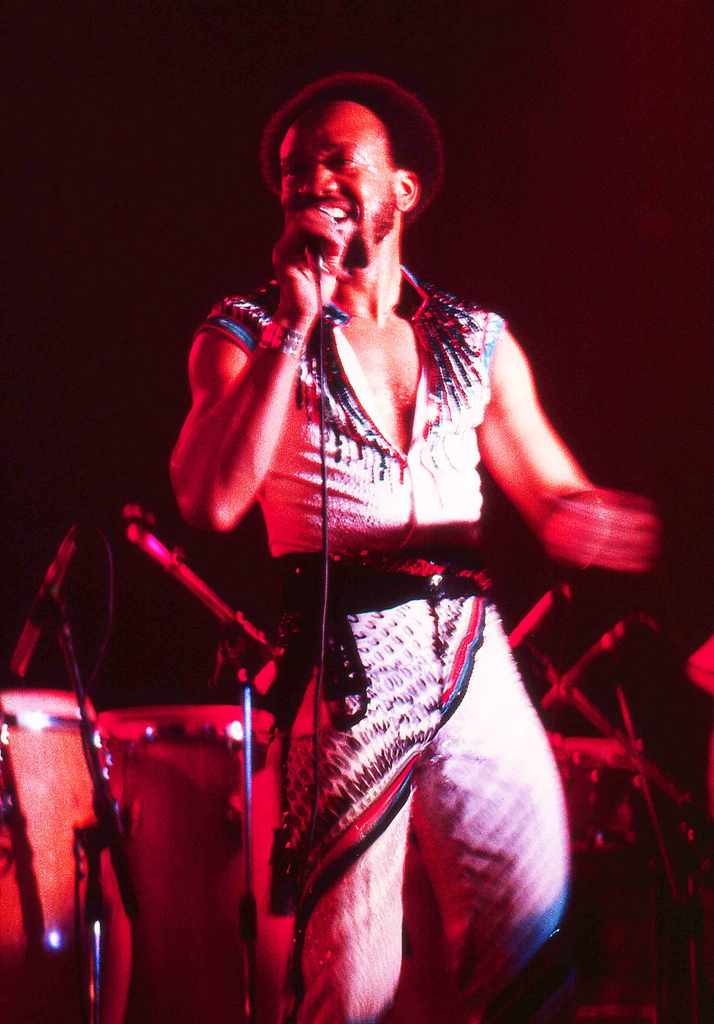

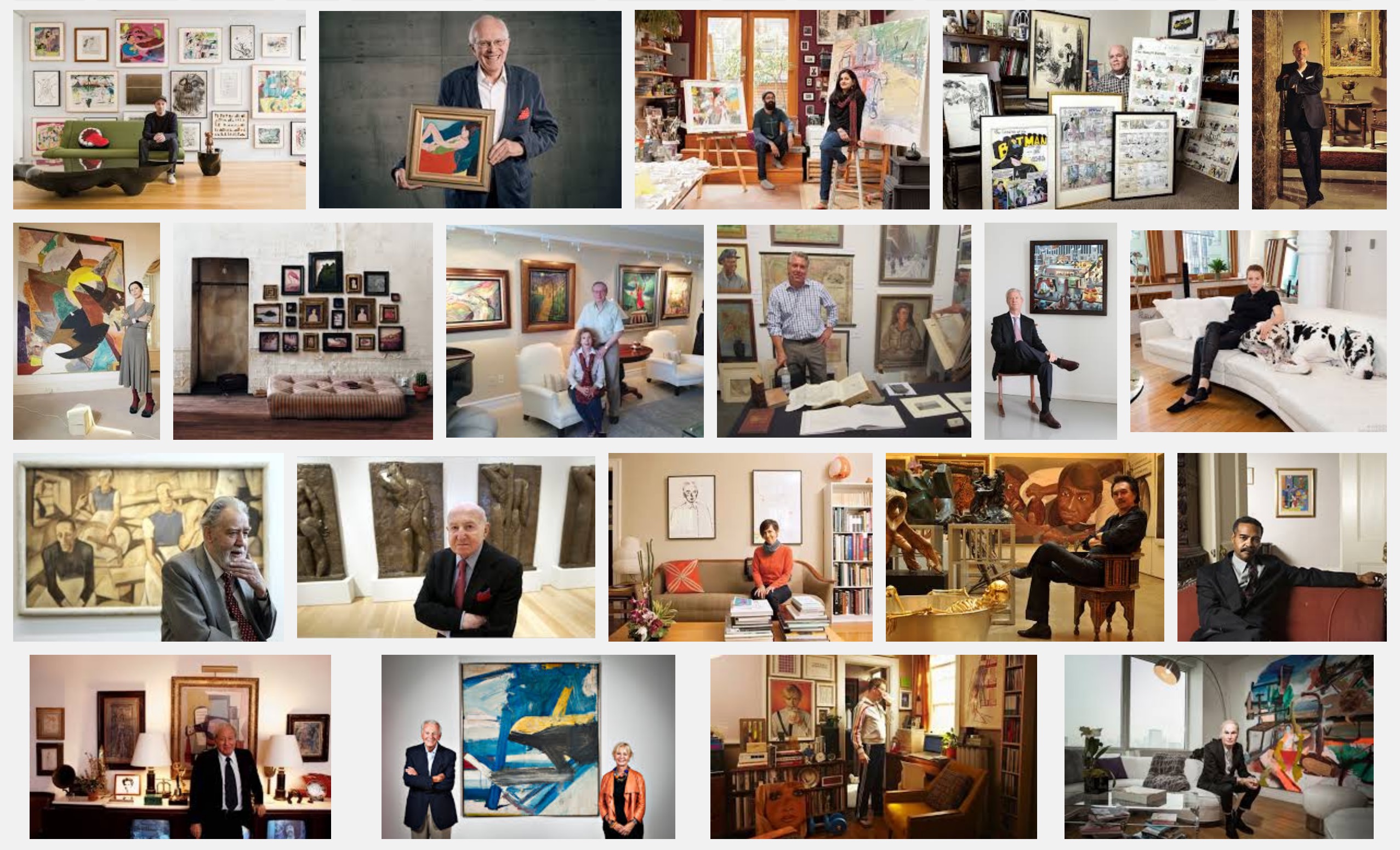

So, I must must admit to awe and a little envy over Zero Freitas’ collection. Over the years he has amassed a vast collection of over 6 million records. During his 40 plus years of collecting he’s evolved from a mere vinyl junkie to a global curator and preservationist.

From the Vinyl Factory:

Nearly everyone interested in records will have, at some point heard, the news that there is a Brazilian who owns millions of records. Fewer seem to know, however, that Zero Freitas, a São Paulo-based businessman now in his sixties, plans to turn his collection into a public archive of the world’s music, with special focus on the Americas. Having amassed over six million records, he manages a collection similar to the entire Discogs database. Given the magnitude of this enterprise, Freitas deals with serious logistical challenges and, above all, time constraints. But he strongly believes it is worth his while. After all, no less than a vinyl library of global proportions is at stake.

How to become a part of this man’s busy timetable – that was the question that remained unanswered almost until the very end of my stay in São Paulo in April 2015. It was 8 am on my second last morning in the city, when Viviane Riegel, my Brazilian partner in crime, received a terse message: ‘if you can make it by 10am to his warehouse, he’ll have an hour for you’. That was our chance. We instantly took a taxi from the city’s south-west part called Campo Belo to a more westerly neighbourhood of Vila Leopoldina. We were privileged enough to listen to Freitas’ stories for what felt like a very quick hundred minutes. His attitude and life’s work provoked compelling questions.

The analogue record in the digital age

What makes any vinyl collection truly valuable? How to tell a mere hoarder from a serious collector? And why is vinyl collectable now, at a time of intensive digitalization of life and culture?

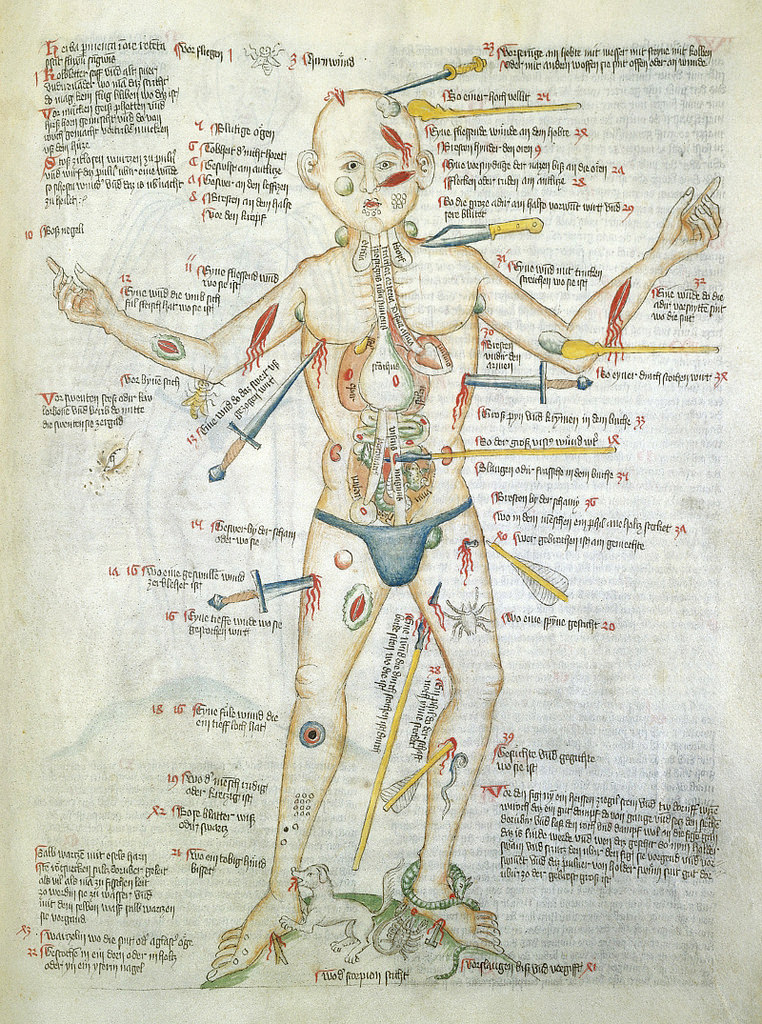

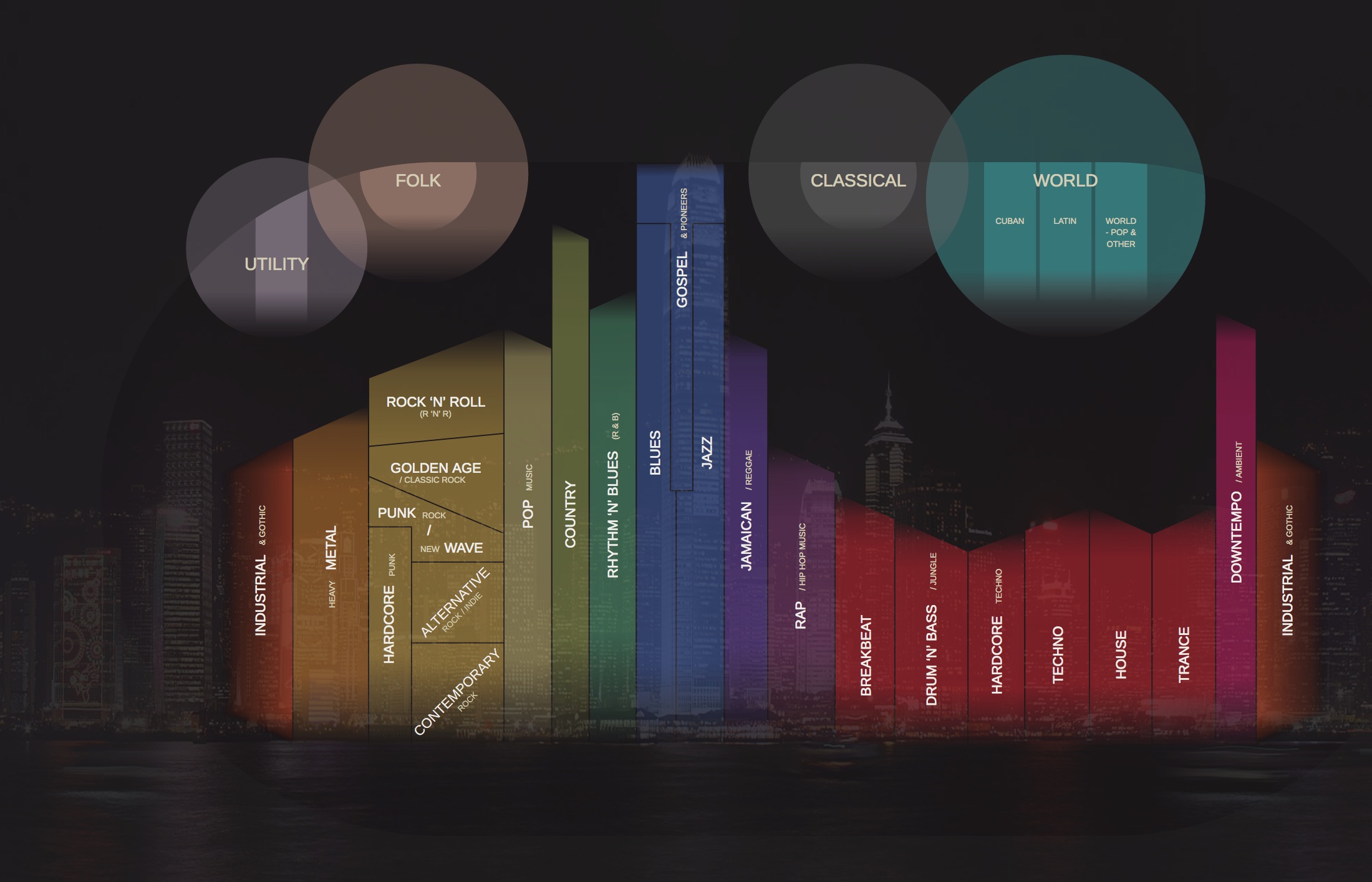

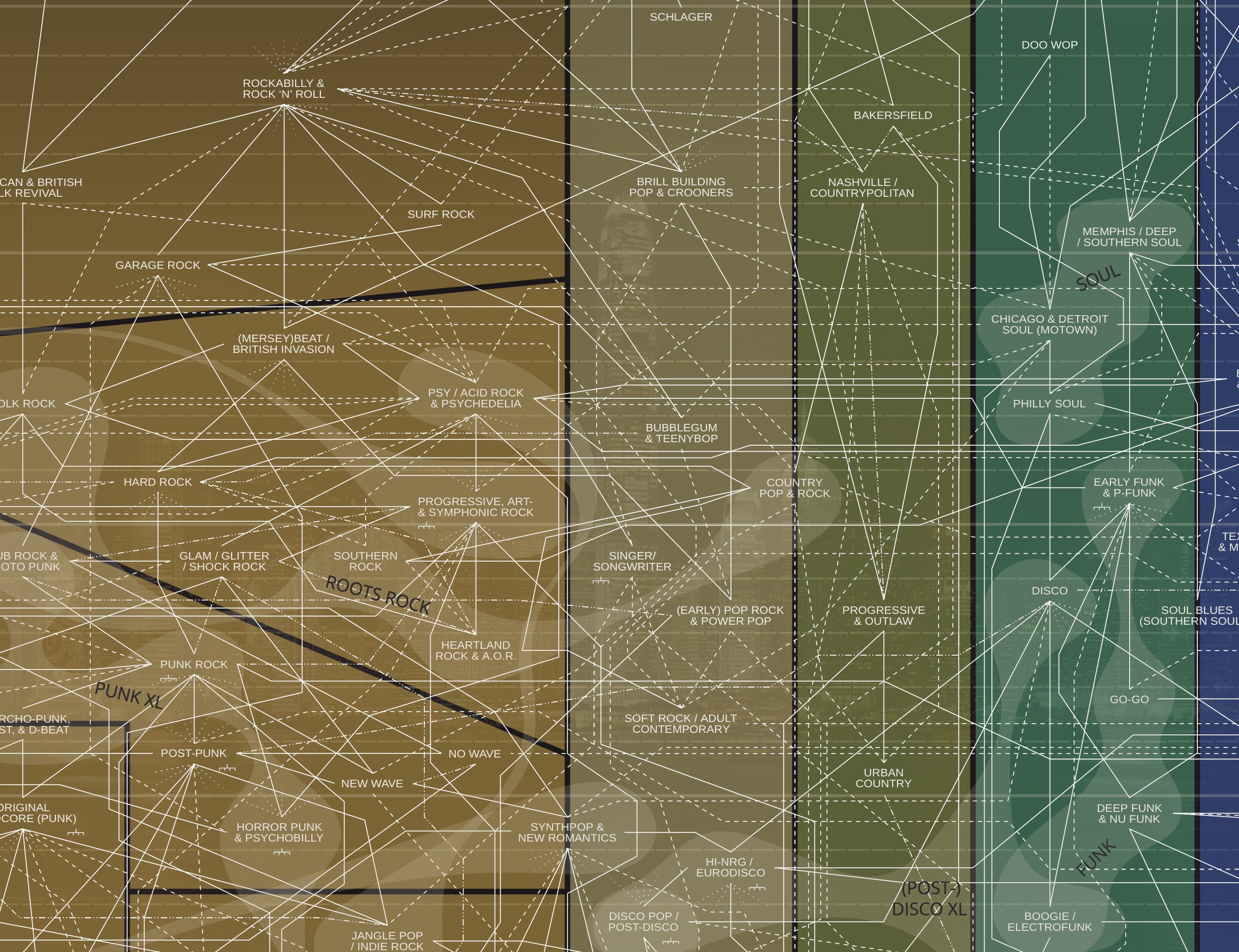

Publically pronounced dead by the mainstream industry in the 1990s, vinyl never really ceased to live and has proved much more resilient than the corporate prophets of digital ‘progress’ would like us to believe. Apart from its unique physical properties, vinyl records contain a history that’s longer than any digital medium can ever hope to replicate. Zero Freitas insists that this history has not been fully told yet. Indeed, when acquired and classified with a set of principles in mind, records may literally offer a record of culture, for they preserve not just sounds, but also artistic expression, visual sensibility, poetry, fashion, ideas of genre differentiation and packaging design, and sometimes social commentary of a given time and place. If you go through your life with records, then your collection might be a record of your life. Big record collections are private libraries of cultural import and aesthetic appeal. They are not so very different from books, a medium we still hold in high regard. Books and records invite ritualistic experience, their digital counterparts offer routine convenience.

The problem is that many records are becoming increasingly rare. As Portuguese musicologist Rui Vieria Nery writes reflecting on the European case of Fado music, “the truth is that, strange as it may seem, collections of Fado recordings as recent as the ’50s to ’70s are difficult to get hold of.“ Zero Freitas emphasizes that the situation of collections from other parts of the world may be even worse.

We have to ask then, what we lose if we don’t get hold of them? For one thing, records preserve the past. They save something intangible from oblivion, where a tune or a cover can suddenly transport us back in time to a younger version of ourselves and the feelings we once had. Rare and independently released records can provide a chance for genuine discovery and learning. They help acquire new tastes, delve into different under-represented stories.

What Thomas Carlyle once wrote about books applies to vinyl perhaps with even greater force: ‘in books lies the soul of the whole past time, the articulate audible voice of the past when the body and material substance of it has altogether vanished like a dream’. This quote is inscribed in stone on the wall of the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Having listened to Zero Freitas, this motto could just as easily apply to his vinyl library project. Focusing on rare Brazilian music, he wants to save some endangered species of vinyl, and thus to raise awareness of world’s vast but jeopardised musical ecologies. This task seems urgent now as our attention span gets ever shorter and more distracted, as reflected in the uprooted samples and truncated snippets of music scattered all over the internet.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Vinyl LPs. Courtesy of the author.

We all need heroes. So, if you wish to become one, you would stand a better chance if you took your dying breaths atop a hill. Also, it would really help your cause if you arrived via virgin birth.

We all need heroes. So, if you wish to become one, you would stand a better chance if you took your dying breaths atop a hill. Also, it would really help your cause if you arrived via virgin birth.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

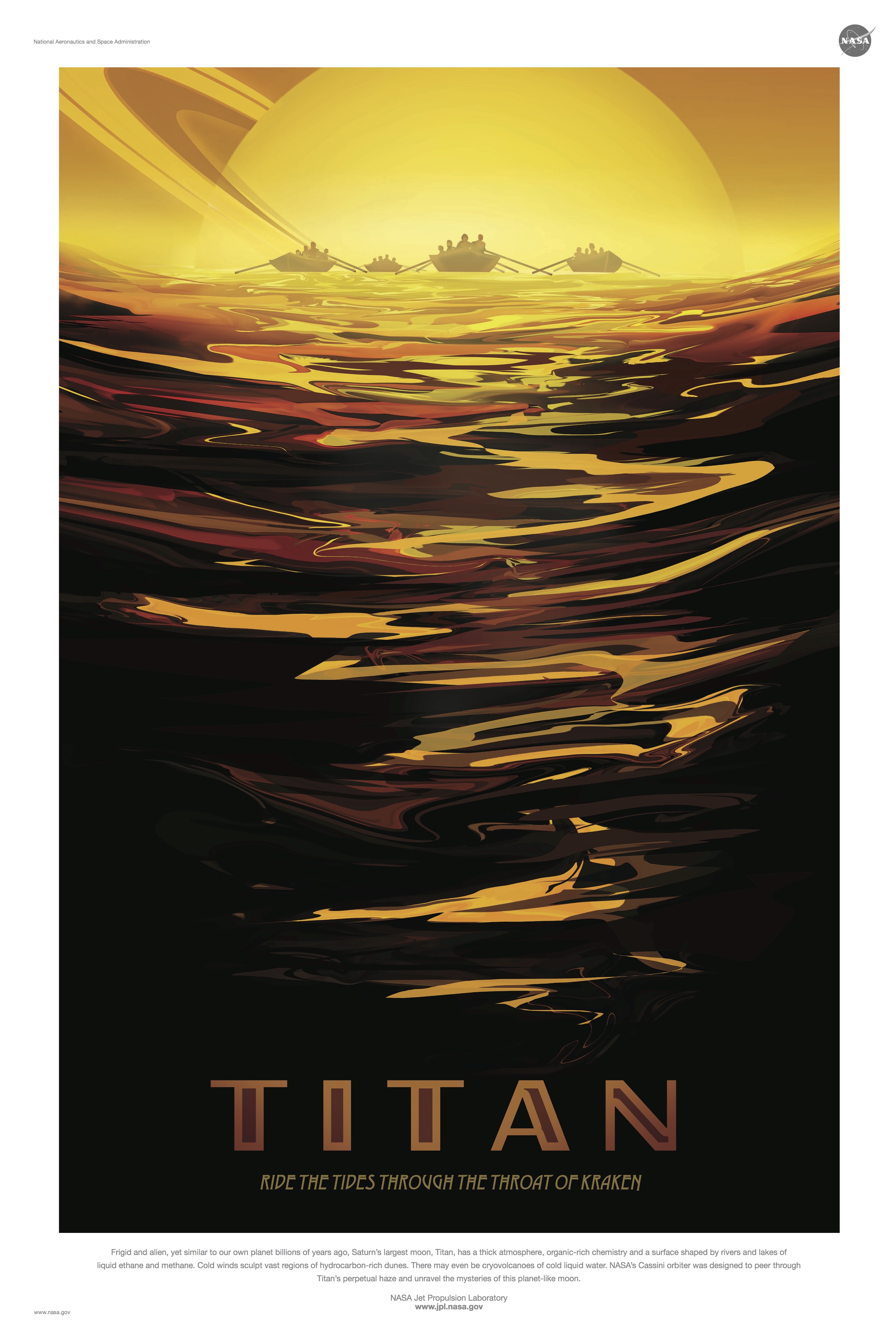

NASA is advertising its upcoming space tourism trip to Saturn’s largest moon Titan with this gorgeous retro poster.

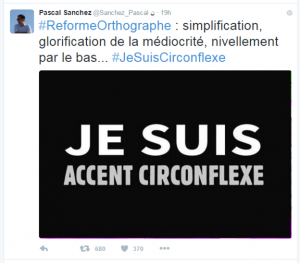

NASA is advertising its upcoming space tourism trip to Saturn’s largest moon Titan with this gorgeous retro poster. The French have a formal language police.

The French have a formal language police. Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?

Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?