[Or, we could have titled this post, “The Original Old World to New World and Visa Versa Infectious Disease Vector].

Syphilis is not some god’s vengeful jest on humanity for certain “deviant” behaviors, according to various televangelists. But, it may well be revenge for the Bubonic Plague. And, Columbus and his fellow explorers could well be to blame for bringing Syphilis back to Europe in exchange for introducing the Americas to smallpox, measles and the plague. What a legacy!

From the Guardian:

Last month, Katherine Wright was awarded the Wellcome Trust science writing prize at a ceremony at the Observer’s offices at Kings Place, London. Wright, who is studying for a DPhil in structural biology at Oxford University, was judged the winner of category A “for professional scientists of postgraduate level and above” from more than 600 entries by a panel including BBC journalist Maggie Philbin, scientist and broadcaster Helen Czerski and the Observer’s Carole Cadwalladr. “I am absolutely thrilled to have won the science writing prize,” says Wright. “This experience has inspired me to continue science writing in the future.”

In the 1490s, a gruesome new disease exploded across Europe. It moved with terrifying speed. Within five years of the first reported cases, among the mercenary army hired by Charles VIII of France to conquer Naples, it was all over the continent and reaching into north Africa. The first symptom was a lesion, or chancre, in the genital region. After that, the disease slowly progressed to the increasingly excruciating later stages. The infected watched their bodies disintegrate, with rashes and disfigurements, while they gradually descended into madness. Eventually, deformed and demented, they died.

Some called it the French disease. To the French, it was the Neapolitan disease. The Russians blamed the Polish. In 1530, an Italian physician penned an epic poem about a young shepherd named Syphilis, who so angered Apollo that the god struck him down with a disfiguring malady to destroy his good looks. It was this fictional shepherd (rather than national rivalries) who donated the name that eventually stuck: the disease, which first ravaged the 16th-century world and continues to affect untold millions today, is now known as syphilis.

As its many names attest, contemporaries of the first spread of syphilis did not know where this disease had come from. Was it indeed the fault of the French? Was it God’s punishment on earthly sinners?

Another school of thought, less xenophobic and less religious, soon gained traction. Columbus’s historic voyage to the New World was in 1492. The Italian soldiers were noticing angry chancres on their genitals by 1494. What if Columbus had brought the disease back to Europe with him as an unwelcome stowaway aboard the Pinta or the Niña?

Since the 1500s, we have discovered a lot more about syphilis. We know it is caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium called Treponema pallidum, and we know that we can destroy this bacterium and cure the disease using antibiotics. (Thankfully we no longer “treat” syphilis with poisonous, potentially deadly mercury, which was used well into the 19th century.)

However, scientists, anthropologists, and historians still disagree about the origin of syphilis. Did Columbus and his sailors really transport the bacterium back from the New World? Or was it just coincidental timing, that the first cases were recorded soon after the adventurers’ triumphant return to the Old World? Perhaps syphilis was already present in the population, but doctors had only just begun to distinguish between syphilis and other disfiguring illnesses such as leprosy; or perhaps the disease suddenly increased in virulence at the end of the 15th century. The “Columbian” hypothesis insists that Columbus is responsible, and the “pre-Columbian” hypothesis that he had nothing to do with it.

Much of the evidence to distinguish between these two hypotheses comes from the skeletal record. Late-stage syphilis causes significant and identifiable changes in the structure of bone, including abnormal growths. To prove that syphilis was already lurking in Europe before Columbus returned, anthropologists would need to identify European skeletons with the characteristic syphilitic lesions, and date those skeletons accurately to a time before 1493.

This has proved a tricky exercise in practice. Identifying past syphilis sufferers in the New World is straightforward: ancient graveyards are overflowing with clearly syphilitic corpses, dating back centuries before Columbus was even born. However, in the Old World, a mere scattering of pre-Columbian syphilis candidates have been unearthed.

Are these 50-odd skeletons the sought-after evidence of pre-Columbian syphilitics? With such a small sample size, it is difficult to definitely diagnose these skeletons with syphilis. There are only so many ways bone can be damaged, and several diseases produce a bone pattern similar to syphilis. Furthermore, the dating methods used can be inexact, thrown off by hundreds of years because of a fish-rich diet, for example.

A study published in 2011 has systematically compared these European skeletons, using rigorous criteria for bone diagnosis and dating. None of the candidate skeletons passed both tests. In all cases, ambiguity in the bone record or the dating made it impossible to say for certain that the skeleton was both syphilitic and pre-Columbian. In other words, there is very little evidence to support the pre-Columbian hypothesis. It seems increasingly likely that Columbus and his crew were responsible for transporting syphilis from the New World to the Old.

Of course, Treponema pallidum was not the only microbial passenger to hitch a ride across the Atlantic with Columbus. But most of the traffic was going the other way: smallpox, measles, and bubonic plague were only some of the Old World diseases which infiltrated the New World, swiftly decimating thousands of Native Americans. Syphilis was not the French disease, or the Polish disease. It was the disease – and the revenge – of the Americas.

Read the entire article here.

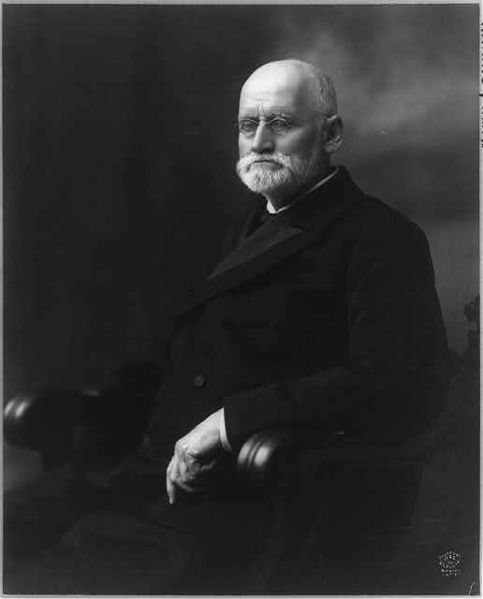

Image: Christopher Columbus by Sebastiano del Piombo (1485–1547). Courtesy of Wikipedia / Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When asked about handedness Nick Moran over a TheMillions says, “everybody’s born right-handed, but the best overcome it.” Funny. And perhaps, now, based on several rings of truth.

When asked about handedness Nick Moran over a TheMillions says, “everybody’s born right-handed, but the best overcome it.” Funny. And perhaps, now, based on several rings of truth.

The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.

The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.