Professional photographers take note: there will always be room for high-quality images that tell a story or capture a timeless event or exude artistic elegance. But, your domain is under attack, again — and the results are not particularly pretty. This time courtesy of Instagram.

Professional photographers take note: there will always be room for high-quality images that tell a story or capture a timeless event or exude artistic elegance. But, your domain is under attack, again — and the results are not particularly pretty. This time courtesy of Instagram.

Just over a hundred years ago, to be a good photographer one required the skills of an alchemist; the chemical processing of plates and prints was more complex, much more time-consuming than capturing the shot itself, and sometimes dangerous. A good print required constant attention, lengthy cajoling and considerable patience, and of course a darkroom and some interesting chemicals.

Then Kodak came along; it commoditized film and processing, expanding photography to the masses. More recently as technology has improved and hardware prices have continued to drop, more cameras have found their ways into the hands of more people. However, until recently access to good quality (yet still expensive) photographic equipment has played an important role in allowing photographers to maintain superiority of their means and ends over everyday amateurs.

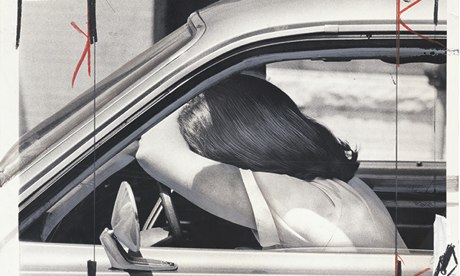

Even as photography has become a primarily digital process, with camera prices continuing to plummet, many photographers have continued to distinguish their finished images from the burgeoning mainstream. After all, it still takes considerable skill and time to post-process an image in Photoshop or other imaging software.

Nowadays, anyone armed with a $99 smartphone is a photographer with a high-resolution camera. And, through the power of blogs and social networks every photographer is also a publisher. Technology has considerably democratized and shortened the process. So, now an image can find its way from the hands of the photographer to the eyes of a vast audience almost instantaneously. The numbers speak for themselves — by most estimates, around 4.2 million images are uploaded daily to Flickr and 4.5 million to Instagram.

And, as the smartphone is to a high-end medium or large format camera, so is Instagram to Photoshop. Now, armed with both smartphone and Instagram a photographer — applying the term loosely — can touch-up an image of their last meal with digital sepia or apply a duo-tone filter to a landscape of their bedroom, or, most importantly, snap a soft-focus, angled self-portrait. All this, and the photographer can still deliver the finished work to a horde of followers for instant, gratuitous “likes”.

But, here’s why Instagram may not be such a threat to photography after all, despite the vast ocean of images washing across the internet.

[div class=attrib]From the Atlantic Wire:[end-div]

While the Internet has had a good time making fun of these rich kid Instagram photos, haters should be careful. These postings are emblematic of the entire medium we all use. To be certain, these wealthy kid pix are particularly funny (and also sad) because they showcase a gross variant of entitlement. Preteens posing with helicopters they did nothing to earn and posting the pictures online for others to ogle provides an easy in for commentary on the state of the American dream. (Dead.) While we don’t disagree with that reading, it’s par for the course on Instagram, a shallow medium all about promoting superficiality that photo takers did little to nothing to earn.

The very basis of Instagram is not just to show off, but to feign talent we don’t have, starting with the filters themselves. The reason we associate the look with “cool” in the first place is that many of these pretty hazes originated from processes coveted either for their artistic or unique merits, as photographer and blogger Ming Thein explains: “Originally, these styles were either conscious artistic decisions, or the consequences of not enough money and using expired film. They were chosen precisely because they looked unique—either because it was a difficult thing to execute well (using tilt-shift lenses, for instance) or because nobody else did it (cross-processing),” he writes. Instagram, however, has made such techniques easy and available, taking away that original value. “It takes the skill out of actually having to do any of these things (learn to process B&W properly, either chemically or in Photoshop, for instance),” he continues.

Yet we apply them to make ourselves look like we’ve got something special. Everything becomes “amaaazzing,” to put it in the words of graphic design blogger Jack Mancer, who has his own screed about the site. But actually, nothing about it is truly amazing. Some might call the process democratizing—everyone is a professional!—but really, it’s a big hoax. Everyone is just pressing buttons to add computer-generated veneers to our mostly mundane lives. There is nothing artsy about that. But we still do it. Is that really better than the rich kids? Sure, we’re not embarrassing ourselves by posting extreme wealth we happened into. But what are we posting? And why? At the very least, we’re doing it to look artsy; if not that, there is some other, deeper, more sinister thing we’re trying to prove, which means we’re right up there with the rich kids.

Here are some examples of how we see this playing out on the network:

The Food Pic

Why you post this: This says my food looks cool, therefore it is yummy. Look how well I eat, or how well I cook, or what a foodie I am.

Why this is just like the rich kids: Putting an artsy filter on a pretty photo can make the grossest slosh look like gourmet eats. It does not prove culinary or photographic skill, it proves that you can press a button.

The Look How much Fun I’m Having Pic

Why you post this: To prove you have the best, most social, coolest life, and friends. To prove you are happy and fun.

Why this is just like the rich kids: This also has an underlying tone of flaunting wealth. Fun usually costs money, and it’s something not everybody else has.

The Picture of Thing Pic

Why you post this: This proves your fantastic, enviable artistic eye: “I turned a mundane object into art!”

What that is just like the rich kids: See above. Essentially, you’re bragging, but without the skills to support it.

Instagram and photo apps like it are shallow mediums that will generate shallow results. They are there for people to showcase something that doesn’t deserve a platform. The rich kids are a particularly salient example of how the entire network operates, but those who live in glass houses shot by Instagram shouldn’t throw beautifully if artfully filtered stones.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Tumblr: Rich Kids of Instgram.[end-div]

The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.

The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.

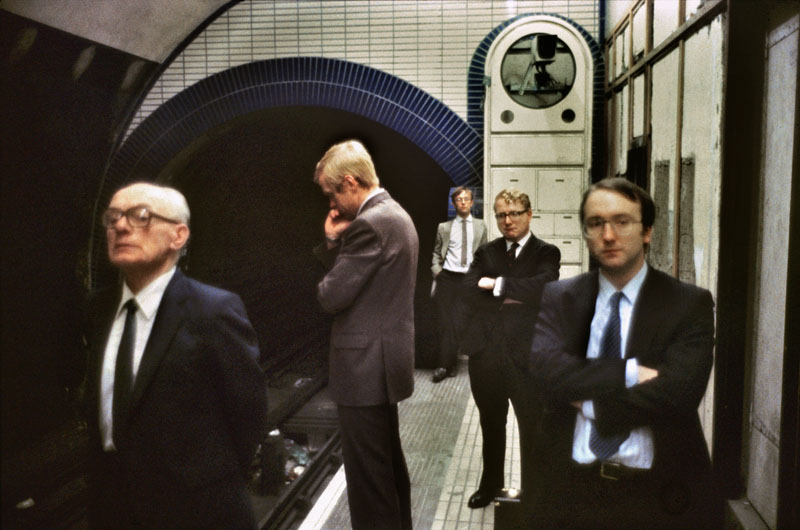

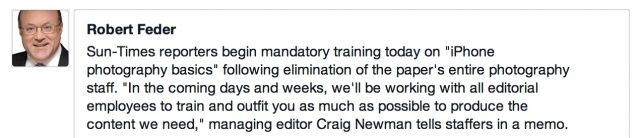

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

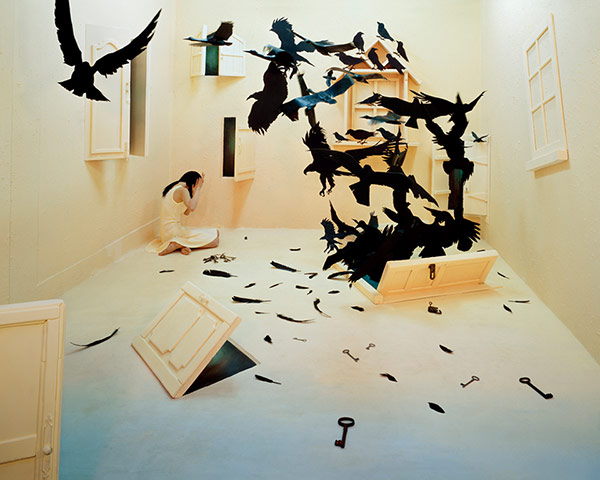

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color.

Please forget Instagram, Photoshop filters, redeye elimination, automatic camera shake reduction systems and high dynamic range apps. If you’re a true photographer or simply a lover of great photography the choice is much simpler: black and white or color. Hint. The answer is not shameless self-promotion or exploitative voyeurism; images used in this way may scratch a personal itch, but rarely influence fundamental societal or political behavior. Importantly, photography has given us a rich, nuanced and lasting medium for artistic expression since cameras and film were first invented. However, the principal answer is lies in photography’s ability to tell truth about and to power.

Hint. The answer is not shameless self-promotion or exploitative voyeurism; images used in this way may scratch a personal itch, but rarely influence fundamental societal or political behavior. Importantly, photography has given us a rich, nuanced and lasting medium for artistic expression since cameras and film were first invented. However, the principal answer is lies in photography’s ability to tell truth about and to power. Professional photographers take note: there will always be room for high-quality images that tell a story or capture a timeless event or exude artistic elegance. But, your domain is under attack, again — and the results are not particularly pretty. This time courtesy of Instagram.

Professional photographers take note: there will always be room for high-quality images that tell a story or capture a timeless event or exude artistic elegance. But, your domain is under attack, again — and the results are not particularly pretty. This time courtesy of Instagram.