A decade ago in another place and era during my days as director of technology research for a Fortune X company I tinkered with a cool array of then new personalization tools. The aim was simple, use some of these emerging technologies to deliver a more customized and personalized user experience for our customers and suppliers. What could be wrong with that? Surely, custom tools and more personalized data could do nothing but improve knowledge and enhance business relationships for all concerned. Our customers would benefit from seeing only the information they asked for, our suppliers would benefit from better analysis and filtered feedback, and we, the corporation in the middle, would benefit from making everyone in our supply chain more efficient and happy. Advertisers would be even happier since with more focused data they would be able to deliver messages that were increasingly more precise and relevant based on personal context.

A decade ago in another place and era during my days as director of technology research for a Fortune X company I tinkered with a cool array of then new personalization tools. The aim was simple, use some of these emerging technologies to deliver a more customized and personalized user experience for our customers and suppliers. What could be wrong with that? Surely, custom tools and more personalized data could do nothing but improve knowledge and enhance business relationships for all concerned. Our customers would benefit from seeing only the information they asked for, our suppliers would benefit from better analysis and filtered feedback, and we, the corporation in the middle, would benefit from making everyone in our supply chain more efficient and happy. Advertisers would be even happier since with more focused data they would be able to deliver messages that were increasingly more precise and relevant based on personal context.

Fast forward to the present. Customization, or filtering, technologies have indeed helped optimize the supply chain; personalization tools and services have made customer experiences more focused and efficient. In today’s online world it’s so much easier to find, navigate and transact when the supplier at the other end of our browser knows who we are, where we live, what we earn, what we like and dislike, and so on. After all, if a supplier knows my needs, requirements, options, status and even personality, I’m much more likely to only receive information, services or products that fall within the bounds that define “me” in the supplier’s database.

And, therein lies the crux of the issue that has helped me to realize that personalization offers a false promise despite the seemingly obvious benefits to all concerned. The benefits are outweighed by two key issues: erosion of privacy and the bubble syndrome.

Privacy as Commodity

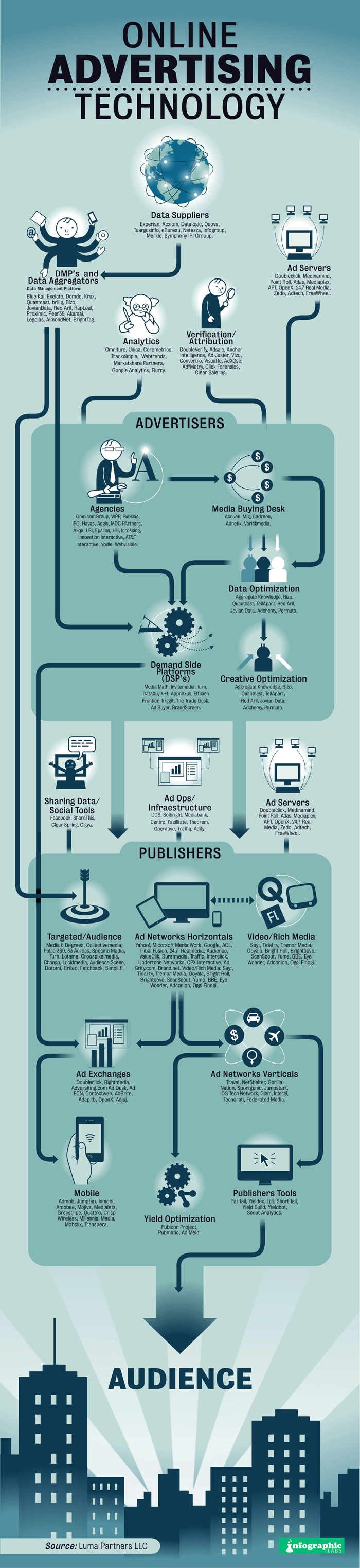

I’ll not dwell too long on the issue of privacy since in this article I’m much more concerned with the personalization bubble. However, as we have increasingly seen in recent times privacy in all its forms is becoming a scarce, and tradable commodity. Much of our data is now in the hands of a plethora of suppliers, intermediaries and their partners, ready for continued monetization. Our locations are constantly pinged and polled; our internet browsers note our web surfing habits and preferences; our purchases generate genius suggestions and recommendations to further whet our consumerist desires. Now in digital form this data is open to legitimate sharing and highly vulnerable to discovery by hackers, phishers and spammers and any with technical or financial resources.

Bubble Syndrome

Personalization technologies filter content at various levels, minutely and broadly, both overtly and covertly. For instance, I may explicitly signal my preferences for certain types of clothing deals at my favorite online retailer by answering a quick retail survey or checking a handful of specific preference buttons on a website.

However, my previous online purchases, browsing behaviors, time spent of various online pages, visits to other online retailers and a range of other flags deliver a range of implicit or “covert” information to the same retailer (and others). This helps the retailer filter, customize and personalize what I get to see even before I have made a conscious decision to limit my searches and exposure to information. Clearly, this is not too concerning when my retailer knows I’m male and usually purchase size 32 inch jeans; after all why would I need to see deals or product information for women’s shoes.

But, this type of covert filtering becomes more worrisome when the data being filtered and personalized is information, news, opinion and comment in all its glorious diversity. Sophisticated media organizations, information portals, aggregators and news services can deliver personalized and filtered information based on your overt and covert personal preferences as well. So, if you subscribe only to a certain type of information based on topic, interest, political persuasion or other dimension your personalized news services will continue to deliver mostly or only this type of information. And, as I have already described, your online behaviors will deliver additional filtering parameters to these news and information providers so that they may further personalize and narrow your consumption of information.

Increasingly, we will not be aware of what we don’t know. Whether explicitly or not, our use of personalization technologies will have the ability to build a filter, a bubble, around us, which will permit only information that we wish to see or that which our online suppliers wish us to see. We’ll not even get exposed to peripheral and tangential information — that information which lies outside the bubble. This filtering of the rich oceans of diverse information to a mono-dimensional stream will have profound implications for our social and cultural fabric.

I assume that our increasingly crowded planet will require ever more creativity, insight, tolerance and empathy as we tackle humanity’s many social and political challenges in the future. And, these very seeds of creativity, insight, tolerance and empathy are those that are most at risk from the personalization filter. How are we to be more tolerant of others’ opinions if we are never exposed to them in the first place? How are we to gain insight when disparate knowledge is no longer available for serendipitous discovery? How are we to become more creative if we are less exposed to ideas outside of our normal sphere, our bubble?

For some ideas on how to punch a few holes in your online filter bubble read Eli Pariser’s practical guide, here.

Filter Bubble image courtesy of TechCrunch.

Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that.

Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that.

The lowly incandescent light bulb continues to come under increasing threat. First, came the fluorescent tube, then the compact fluorescent. More recently the LED (light emitting diode) seems to be gaining ground. Now LED technology takes another leap forward with printed LED “light sheets”.

The lowly incandescent light bulb continues to come under increasing threat. First, came the fluorescent tube, then the compact fluorescent. More recently the LED (light emitting diode) seems to be gaining ground. Now LED technology takes another leap forward with printed LED “light sheets”. Computer hardware reached (or plummeted, depending upon your viewpoint) the level of commodity a while ago. And of course, some types of operating systems platforms, and software and applications have followed suit recently — think Platform as a Service (PaaS) and Software as a Service (SaaS). So, it should come as no surprise to see new services arise that try to match supply and demand, and profit in the process. Welcome to the “cloud brokerage”.

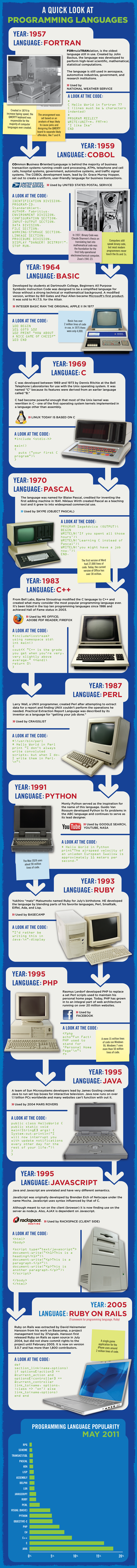

Computer hardware reached (or plummeted, depending upon your viewpoint) the level of commodity a while ago. And of course, some types of operating systems platforms, and software and applications have followed suit recently — think Platform as a Service (PaaS) and Software as a Service (SaaS). So, it should come as no surprise to see new services arise that try to match supply and demand, and profit in the process. Welcome to the “cloud brokerage”. Last week on October 8, 2011, Dennis Richie passed away. Most of the mainstream media failed to report his death — after all he was never quite as flamboyant as another technology darling, Steve Jobs. However, his contributions to the worlds of technology and computer science should certainly place him in the same club.

Last week on October 8, 2011, Dennis Richie passed away. Most of the mainstream media failed to report his death — after all he was never quite as flamboyant as another technology darling, Steve Jobs. However, his contributions to the worlds of technology and computer science should certainly place him in the same club. The world will miss Steve Jobs.

The world will miss Steve Jobs.

Frequent fliers the world over may soon find themselves thanking a physicist named Jason Steffen. Back in 2008 he ran some computer simulations to find a more efficient way for travelers to board an airplane. Recent tests inside a mock cabin interior confirmed Steffen’s model to be both faster for the airline and easier for passengers, and best of all less time spent waiting in the aisle and jostling for overhead bin space.

Frequent fliers the world over may soon find themselves thanking a physicist named Jason Steffen. Back in 2008 he ran some computer simulations to find a more efficient way for travelers to board an airplane. Recent tests inside a mock cabin interior confirmed Steffen’s model to be both faster for the airline and easier for passengers, and best of all less time spent waiting in the aisle and jostling for overhead bin space. Cities are one of the most remarkable and peculiar inventions of our species. They provide billions in the human family a framework for food, shelter and security. Increasingly, cities are becoming hubs in a vast data network where public officials and citizens mine and leverage vast amounts of information.

Cities are one of the most remarkable and peculiar inventions of our species. They provide billions in the human family a framework for food, shelter and security. Increasingly, cities are becoming hubs in a vast data network where public officials and citizens mine and leverage vast amounts of information.

That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

It’s #$% hot in the southern plains of the United States, with high temperatures constantly above 100 degrees F, and lows never dipping below 80. For that matter, it’s hotter than average this year in most parts of the country. So, a timely article over at Slate gives a great overview of the history of the air conditioning system, courtesy of inventor Willis Carrier.

It’s #$% hot in the southern plains of the United States, with high temperatures constantly above 100 degrees F, and lows never dipping below 80. For that matter, it’s hotter than average this year in most parts of the country. So, a timely article over at Slate gives a great overview of the history of the air conditioning system, courtesy of inventor Willis Carrier. The lives of 2 technological marvels came to a close this week. First, NASA officially concluded the space shuttle program with the

The lives of 2 technological marvels came to a close this week. First, NASA officially concluded the space shuttle program with the

[div class=attrib]From ReadWriteWeb:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From ReadWriteWeb:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]