QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No.

QTWTAIN is a Twitterspeak acronym for a Question To Which The Answer Is No.

QTWTAINs are a relatively recent journalistic phenomenon. They are often used as headlines to great effect by media organizations to grab a reader’s attention. But importantly, QTWTAINs imply that something ridiculous is true — by posing a headline as a question no evidence seems to be required. Here’s an example of a recent headline:

“Europe: Are there Nazis living on the moon?”

Author and journalist John Rentoul has done all connoisseurs of QTWTAINs a great service by collecting an outstanding selection from hundreds of his favorites into a new book, Questions to Which the Answer is No. Rentoul tells us his story, excerpted, below.

[div class=attrib]From the Independent:[end-div]

I have an unusual hobby. I collect headlines in the form of questions to which the answer is no. This is a specialist art form that has long been a staple of “prepare to be amazed” journalism. Such questions allow newspapers, television programmes and websites to imply that something preposterous is true without having to provide the evidence.

If you see a question mark after a headline, ask yourself why it is not expressed as a statement, such as “Church of England threatened by excess of cellulite” or “Revealed: Marlene Dietrich plotted to murder Hitler” or, “This penguin is a communist”.

My collection started with a bishop, a grudge against Marks & Spencer and a theft in broad daylight. The theft was carried out by me: I had been inspired by Oliver Kamm, a friend and hero of mine, who wrote about Great Historical Questions to Which the Answer is No on his blog. Then I came across this long headline in Britain’s second-best-selling newspaper three years ago: “He’s the outcast bishop who denies the Holocaust – yet has been welcomed back by the Pope. But are Bishop Williamson’s repugnant views the result of a festering grudge against Marks & Spencer?” Thus was an internet meme born.

Since then readers of The Independent blog and people on Twitter with nothing better to do have supplied me with a constant stream of QTWTAIN. If this game had a serious purpose, which it does not, it would be to make fun of conspiracy theories. After a while, a few themes recurred: flying saucers, yetis, Jesus, the murder of John F Kennedy, the death of Marilyn Monroe and reincarnation.

An enterprising PhD student could use my series as raw material for a thesis entitled: “A Typology of Popular Irrationalism in Early 21st-Century Media”. But that would be to take it too seriously. The proper use of the series is as a drinking game, to be followed by a rousing chorus of “Jerusalem”, which consists largely of questions to which the answer is no.

My only rule in compiling the series is that the author or publisher of the question has to imply that the answer is yes (“Does Nick Clegg Really Expect Us to Accept His Apology?” for example, would be ruled out of order). So far I have collected 841 of them, and the best have been selected for a book published this week. I hope you like them.

Is the Loch Ness monster on Google Earth?

Daily Telegraph, 26 August 2009

A picture of something that actually looked like a giant squid had been spotted by a security guard as he browsed the digital planet. A similar question had been asked by the Telegraph six months earlier, on 19 February, about a different picture: “Has the Loch Ness Monster emigrated to Borneo?”

Would Boudicca have been a Liberal Democrat?

This one is cheating, because Paul Richards, who asked it in an article in Progress magazine, 12 March 2010, did not imply that the answer was yes. He was actually making a point about the misuse of historical conjecture, comparing Douglas Carswell, the Conservative MP, who suggested that the Levellers were early Tories, to the spiritualist interviewed by The Sun in 1992, who was asked how Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, Karl Marx and Chairman Mao would have voted (Churchill was for John Major; the rest for Neil Kinnock, naturally).

Is Tony Blair a Mossad agent?

A question asked by Peza, who appears to be a cat, on an internet forum on 9 April 2010. One reader had a good reply: “Peza, are you drinking that vodka-flavoured milk?”

Could Angelina Jolie be the first female US President?

Daily Express, 24 June 2009

An awkward one this, because one of my early QTWTAIN was “Is the Express a newspaper?” I had formulated an arbitrary rule that its headlines did not count. But what are rules for, if not for changing?

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump?[end-div]

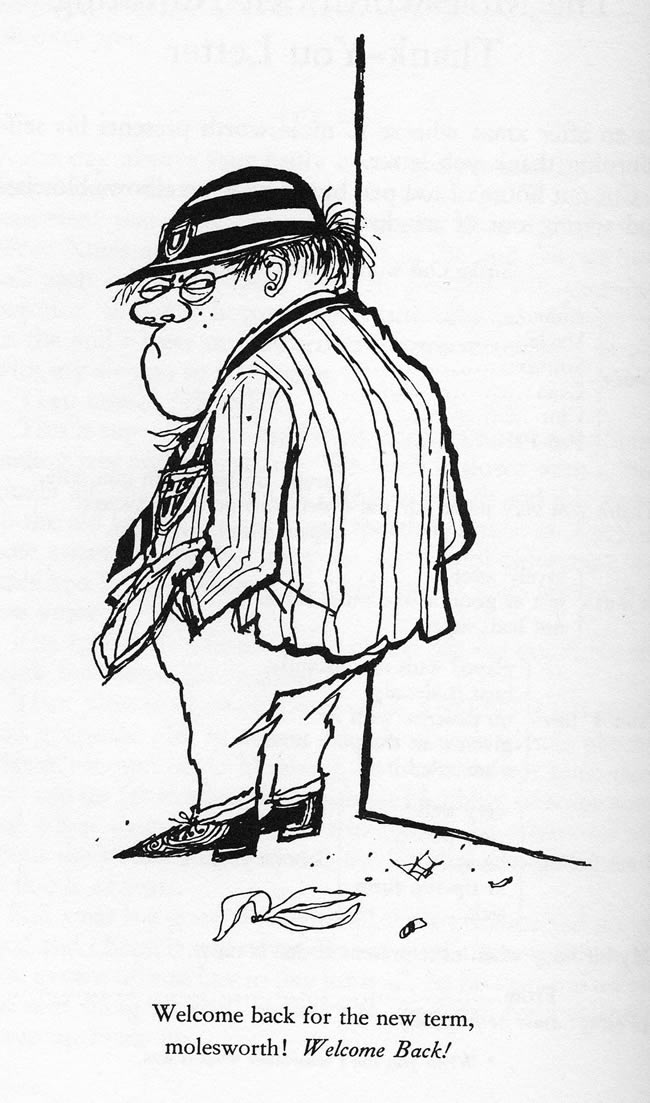

[div class=attrib]Book Cover: Questions to Which the Answer is No, by John Rentoul. Courtesy of the Independent / John Rentoul.[end-div]

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

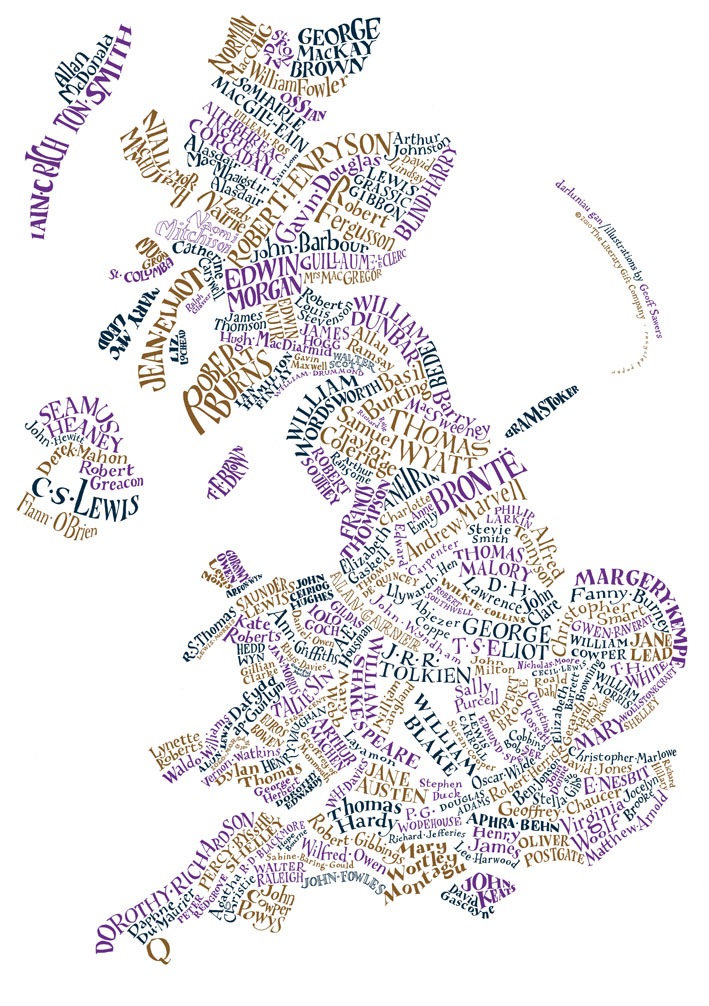

The official start of summer in the northern hemisphere is just over a week away. So, it’s time to gather together some juicy reads for lazy days by the beach or under a sturdy shade tree. Flavorwire offers a classic list of 30 reads with a couple of surprises thrown in. And, we’ll qualify Flavorwire’s selection by adding that anyone over 30 should read these works as well.

The official start of summer in the northern hemisphere is just over a week away. So, it’s time to gather together some juicy reads for lazy days by the beach or under a sturdy shade tree. Flavorwire offers a classic list of 30 reads with a couple of surprises thrown in. And, we’ll qualify Flavorwire’s selection by adding that anyone over 30 should read these works as well.

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

“Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.” [From Fahrenheit 451].

Professor of philosophy Simon Critchley has an insightful examination (serialized) of Philip K. Dick’s writings. Philip K. Dick had a tragically short, but richly creative writing career. Since his death twenty years ago, many of his novels have profoundly influenced contemporary culture.

Professor of philosophy Simon Critchley has an insightful examination (serialized) of Philip K. Dick’s writings. Philip K. Dick had a tragically short, but richly creative writing career. Since his death twenty years ago, many of his novels have profoundly influenced contemporary culture.

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,  French children, it seems, unlike their cousins in the United States, don’t suffer temper tantrums, sit patiently at meal-times, defer to their parents, eat all their vegetables, respect adults, and are generally happy. Why is this and should American parents ditch the latest pop psychology handbooks for parenting lessons from La Belle France?

French children, it seems, unlike their cousins in the United States, don’t suffer temper tantrums, sit patiently at meal-times, defer to their parents, eat all their vegetables, respect adults, and are generally happy. Why is this and should American parents ditch the latest pop psychology handbooks for parenting lessons from La Belle France?

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen.

We celebrate the arrival of winter to the northern hemisphere with an evocative poem by Kenneth Patchen. Robert Hayden is generally accepted as one of the premier authors of African American poetry. His expertly crafted poems focusing on the black historical experience earned him numerous awards.

Robert Hayden is generally accepted as one of the premier authors of African American poetry. His expertly crafted poems focusing on the black historical experience earned him numerous awards. Fahrenheit 2,451 may well be the temperature at which the glass in your Kindle or Nook eReader is likely to melt. This may give Ray Bradbury mixed feelings.

Fahrenheit 2,451 may well be the temperature at which the glass in your Kindle or Nook eReader is likely to melt. This may give Ray Bradbury mixed feelings. Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language.

Dante Alighieri is held in high regard in Italy, where he is often referred to as il Poeta, the poet. He is best known for the monumental poem La Commedia, later renamed La Divina Commedia – The Divine Comedy. Scholars consider it to be the greatest work of literature in the Italian language. Many also consider Dante to be symbolic father of the Italian language. A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy.

A chronicler of the human condition and deeply personal emotion, poet Sharon Olds is no shrinking violet. Her contemporary poems have been both highly praised and condemned for their explicit frankness and intimacy. Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin.

Poet, essayist and playwright Todd Hearon grew up in North Carolina. He earned a PhD in editorial studies from Boston University. He is winner of a number of national poetry and playwriting awards including the 2007 Friends of Literature Prize and a Dobie Paisano Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin. Joy Harjo is an acclaimed poet, musician and noted teacher. Her poetry is grounded in the United States’ Southwest and often encompasses Native American stories and values.

Joy Harjo is an acclaimed poet, musician and noted teacher. Her poetry is grounded in the United States’ Southwest and often encompasses Native American stories and values.

This week, theDiagonal focuses its energies on that most precious of natural resources — water.

This week, theDiagonal focuses its energies on that most precious of natural resources — water.