Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

“How did the art world become such a vapid hell-hole of investment-crazed pretentiousness?”

In his scathing attack on the contemporary art scene replete with Twitter feeds, pool parties, and gallery-curated designer cheese, Coonan quite rightly asks why window dressing and marketing have replaced artistry and craftsmanship. And, more importantly, has big money replaced great, new art?

As an example, the biggest news from Art Basel, the biggest art show in the United States, is not art at all. Celebrity contemporary artist Jeff Koons’ has defected to a rival gallery from his previous home with Larry Gagosian. Gagosian to the art cognoscenti is the “world’s most powerful art dealer”.

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Freud said the goals of the artist are fame, money, and beautiful lovers. Based on my artist acquaintances, I would say this holds true today. What have changed, however, are the goals of the art itself. Do any exist?

How did the art world become such a vapid hell-hole of investment-crazed pretentiousness? How did it become, as Camille Paglia has recently described it, a place where “too many artists have lost touch with the general audience and have retreated to an airless echo chamber”? (More from her in a moment.)

There are sundry problems bedeviling the contemporary art scene. Here are eight that spring readily to mind:

1. Art Basel Miami.

It’s baaa-ack, and I, for one, will not be attending. The overblown art fair in Miami—an offshoot of the original, held in Basel, Switzerland—has become a promo-party cheese-fest. All that craven socializing and trendy posing epitomize the worst aspects of today’s scene, provoking in me a strong desire to start a Thomas Kinkade collection. Whenever some hapless individual innocently asks me if I will be attending Art Basel—even though the shenanigans don’t start for another two weeks, I am already getting e-vites for pre-Basel parties—I invariably respond in Tourette’s mode:

“No. In fact, I would rather jump in a river of boiling snot, which is ironic since that could very well be the title of a faux-conceptual installation one might expect to see at Art Basel. Have you seen Svetlana’s new piece? It’s a river of boiling snot. No, I’m not kidding. And, guess what, Charles Saatchi wants to buy it and is duking it out with some Russian One Percent-er.”

2. Blood, poo, sacrilege, and porn.

Old-school ’70s punk shock tactics are so widespread in today’s art world that they have lost any resonance. As a result, twee paintings like Gainsborough’s Blue Boy and Constable’s Hay Wain now appear mesmerizing, mysterious, and wildly transgressive. And, as Camille Paglia brilliantly argues in her must-read new book, Glittering Images, this torrent of penises, elephant dung, and smut has not served the broader interests of art. By providing fuel for the Rush Limbaugh-ish prejudice that the art world is full of people who are shoving yams up their bums and doing horrid things to the Virgin Mary, art has, quoting Camille again, “allowed itself to be defined in the public eye as an arrogant, insular fraternity with frivolous tastes and debased standards.” As a result, the funding of school and civic arts programs has screeched to a halt and “American schoolchildren are paying the price for the art world’s delusional sense of entitlement.” Thanks a bunch, Karen Finley, Chris Ofili, Andres Serrano, Damien Hirst, and the rest of you naughty pranksters!

Any taxpayers not yet fully aware of the level of frivolity and debasement to which art has plummeted need look no further than the Museum of Modern Art, which recently hosted a jumbo garage-sale-cum-performance piece created by one Martha Rosler titled “Meta-Monumental Garage Sale.” Maybe this has some reverse-chic novelty for chi-chi arty insiders, but for the rest of us out here in the real world, a garage sale is just a garage sale.

…

8. Cool is corrosive.

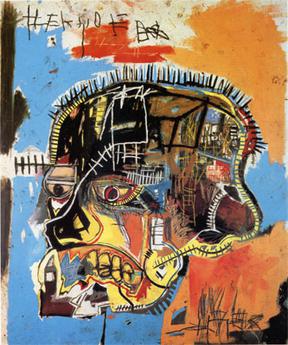

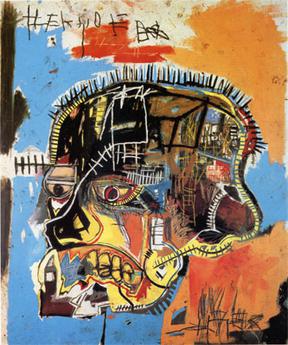

The dorky uncool ’80s was a great time for art. The Harings, Cutrones, Scharfs, and Basquiats—life-enhancing, graffiti-inspired painters—communicated a simple, relevant, populist message of hope and flava during the darkest years of the AIDS crisis. Then, in the early ‘90s, grunge arrived, and displaced the unpretentious communicative culture of the ‘80s with the dour obscurantism of COOL. Simple fun and emotional sincerity were now seen as embarrassing and deeply uncool. Enter artists like Rachel barrel-of-laughs Whiteread, who makes casts of the insides of cardboard boxes. (Nice work if you can get it!)

A couple of decades on, art has become completely pickled in the vinegar of COOL, and that is why it is so irrelevant to the general population.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article following the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Untitled acrylic and mixed media on canvas by Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1984. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence?

Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence? On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great.

On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great.

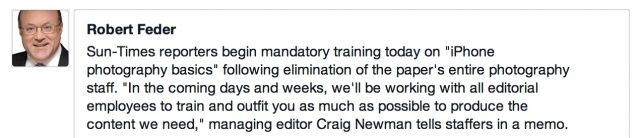

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

Artist Ai Weiwei has suffered at the hands of the Chinese authorities much more so than Andy Warhol’s brushes with surveillance from the FBI. Yet the two are remarkably similar: brash and polarizing views, distinctive art and creative processes, masterful self-promotion, savvy media manipulation and global ubiquity. This is all the more astounding given Ai Weiwei’s arrest, detentions and prohibition on travel outside of Beijing. He’s even made it to the Venice Biennale this year — only his art of course.

Artist Ai Weiwei has suffered at the hands of the Chinese authorities much more so than Andy Warhol’s brushes with surveillance from the FBI. Yet the two are remarkably similar: brash and polarizing views, distinctive art and creative processes, masterful self-promotion, savvy media manipulation and global ubiquity. This is all the more astounding given Ai Weiwei’s arrest, detentions and prohibition on travel outside of Beijing. He’s even made it to the Venice Biennale this year — only his art of course. If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time.

If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time. That a small group of Young British Artists (YBA) made an impact on the art scene in the UK and across the globe over the last 25 years is without question. Though, whether the public at large will, 10, 25 or 50 years from now (and beyond), recognize a Damien Hirst spin painting or Tracy Emin’s “My Bed” or a Sarah Lucas self-portrait — “The Artist Eating a Banana” springs to mind — remains an open question.

That a small group of Young British Artists (YBA) made an impact on the art scene in the UK and across the globe over the last 25 years is without question. Though, whether the public at large will, 10, 25 or 50 years from now (and beyond), recognize a Damien Hirst spin painting or Tracy Emin’s “My Bed” or a Sarah Lucas self-portrait — “The Artist Eating a Banana” springs to mind — remains an open question. Last week Amazon purchased Goodreads the online book review site. Since 2007 Goodreads has grown to become home to over 16 million members who share a passion for discovering and sharing great literature. Now, with Amazon’s acquisition many are concerned that this represents another step towards a monolithic and monopolistic enterprise that controls vast swathes of the market. While Amazon’s innovation has upended the bricks-and-mortar worlds of publishing and retailing, its increasingly dominant market power raises serious concerns over access, distribution and choice. This is another worrying example of the so-called filter bubble — where increasingly edited selections and personalized recommendations act to limit and dumb-down content.

Last week Amazon purchased Goodreads the online book review site. Since 2007 Goodreads has grown to become home to over 16 million members who share a passion for discovering and sharing great literature. Now, with Amazon’s acquisition many are concerned that this represents another step towards a monolithic and monopolistic enterprise that controls vast swathes of the market. While Amazon’s innovation has upended the bricks-and-mortar worlds of publishing and retailing, its increasingly dominant market power raises serious concerns over access, distribution and choice. This is another worrying example of the so-called filter bubble — where increasingly edited selections and personalized recommendations act to limit and dumb-down content. Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

Where is the technology of the Culture when it’s most needed? Nothing more to add.

You could be forgiven for mistakenly assuming this story to be a work of pop fiction from the colorful and restless minds of Quentin Tarrantino or the Coen brothers. But in another example of life mirroring art, it’s all true.

You could be forgiven for mistakenly assuming this story to be a work of pop fiction from the colorful and restless minds of Quentin Tarrantino or the Coen brothers. But in another example of life mirroring art, it’s all true. No, we don’t mean war on apostasy, for which many have been hung, drawn, quartered, burned and beheaded. And no, “apostrophes” are not a new sect of fundamentalist terrorists.

No, we don’t mean war on apostasy, for which many have been hung, drawn, quartered, burned and beheaded. And no, “apostrophes” are not a new sect of fundamentalist terrorists. To

To

Only yesterday we

Only yesterday we  Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world.

Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world. Emily Dickinson has been much written about, but still remains enigmatic. Many of her peers thought her to be eccentric and withdrawn. Only after her death did the full extent of her prolific writing become apparent. To this day, her unique poetry is regarded as having ushered in a new era of personal observation and expression.

Emily Dickinson has been much written about, but still remains enigmatic. Many of her peers thought her to be eccentric and withdrawn. Only after her death did the full extent of her prolific writing become apparent. To this day, her unique poetry is regarded as having ushered in a new era of personal observation and expression.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another. The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question: