Previous generations worried about Frankenstein, evil robots, even more evil aliens, hungry dinosaurs and, more recently, vampires. Nowadays our culture seems to be singularly obsessed with zombies. Why?

From the Conversation:

The zombie invasion is here. Our bookshops, cinemas and TVs are dripping with the pustulating debris of their relentless shuffle to cultural domination.

A search for “zombie fiction” on Amazon currently provides you with more than 25,000 options. Barely a week goes by without another onslaught from the living dead on our screens. We’ve just seen the return of one of the most successful of these, The Walking Dead, starring Andrew Lincoln as small-town sheriff, Rick Grimes. The show follows the adventures of Rick and fellow survivors as they kill lots of zombies and increasingly, other survivors, as they desperately seek safety.

Generational monsters

Since at least the late 19th century each generation has created fictional enemies that reflect a broader unease with cultural or scientific developments. The “Yellow Peril” villains such as Fu Manchu were a response to the massive increase in Chinese migration to the US and Europe from the 1870s, for example.

As the industrial revolution steamed ahead, speculative fiction of authors such as H G Wells began to consider where scientific innovation would take mankind. This trend reached its height in the Cold War during the 1950s and 1960s. Radiation-mutated monsters and invasions from space seen through the paranoid lens of communism all postulated the imminent demise of mankind.

By the 1970s, in films such as The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor, the enemy evolved into government institutions and powerful corporations. This reflected public disenchantment following years of increasing social conflict, Vietnam and the Watergate scandal.

In the 1980s and 1990s it was the threat of AIDS that was embodied in the monsters of the era, such as “bunny boiling” stalker Alex in Fatal Attraction. Alex’s obsessive pursuit of the man with whom she shared a one night stand, Susanne Leonard argues, represented “the new cultural alignment between risk and sexual contact”, a theme continued with Anne Rices’s vampire Lestat in her series The Vampire Chronicles.

Risk and anxiety

Zombies, the flesh eating undead, have been mentioned in stories for more than 4,000 years. But the genre really developed with the work of H G Wells, Poe and particularly H P Lovecraft in the early 20th century. Yet these ponderous adversaries, descendants of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, have little in common with the vast hordes that threaten mankind’s existence in the modern versions.

M Keith Booker argued that in the 1950s, “the golden age of nuclear fear”, radiation and its fictional consequences were the flip side to a growing faith that science would solve the world’s problems. In many respects we are now living with the collapse of this faith. Today we live in societies dominated by an overarching anxiety reflecting the risk associated with each unpredictable scientific development.

Now we know that we are part of the problem, not necessarily the solution. The “breakthroughs” that were welcomed in the last century now represent some of our most pressing concerns. People have lost faith in assumptions of social and scientific “progress”.

Globalisation

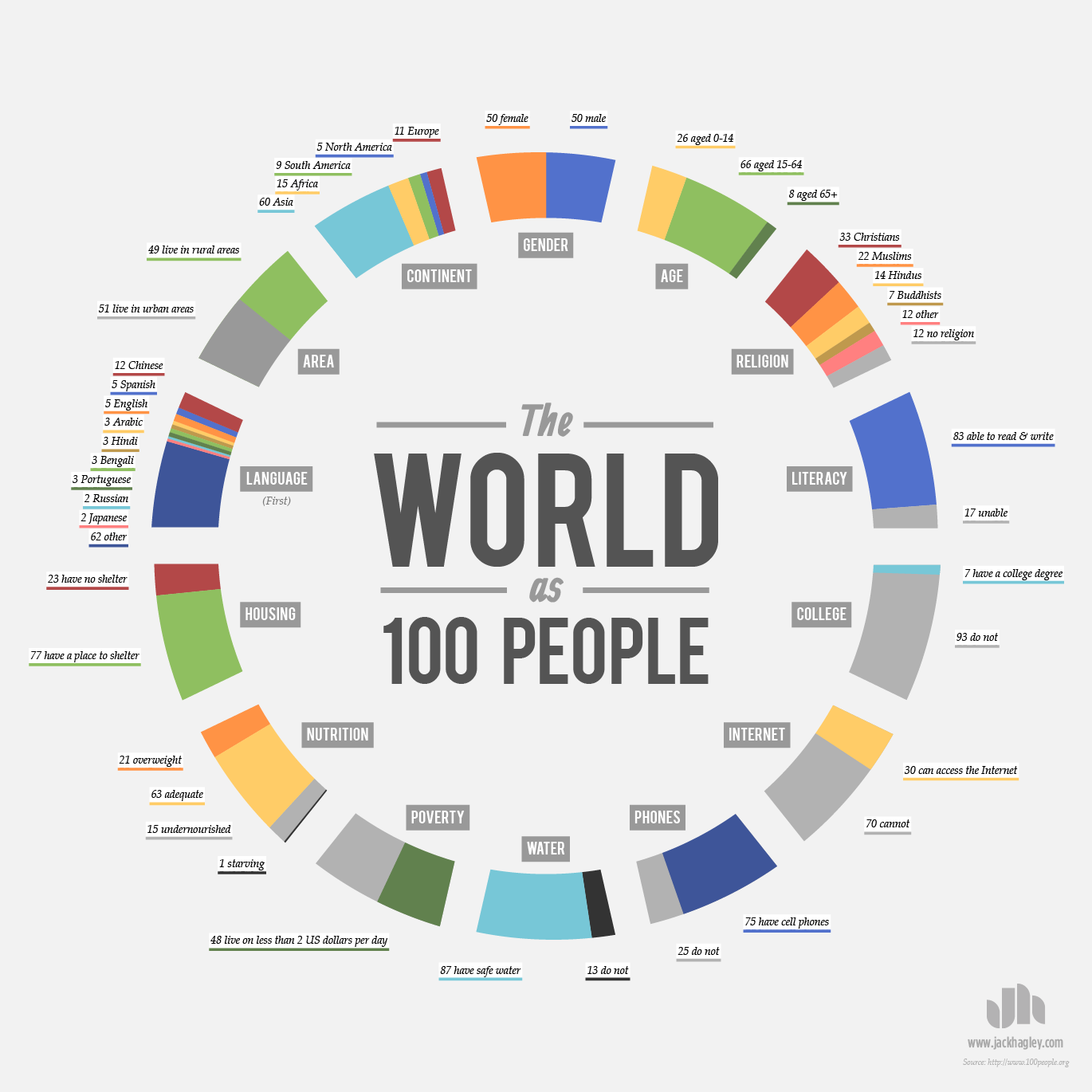

Central to this is globalisation. While generating enormous benefits, globalisation is also tearing communities apart. The political landscape is rapidly changing as established political institutions seem unable to meet the challenges presented by the social and economic dislocation.

However, although destructive, globalisation is also forging new links between people, through what Anthony Giddens calls the “emptying of time and space”. Modern digital media has built new transnational alliances, and, particularly in the West, confronted people with stark moral questions about the consequences of their own lifestyles.

As the faith in inexorable scientific “progress” recedes, politics is transformed. The groups emerging from outside the political mainstream engage in much older battles of faith and identity. Whether right-wing nationalists or Islamic fundamentalists, they seek to build “imagined communities” through race, religion or culture and “fear” is their currency.

Evolving zombies

Modern zombies are the product of this globalised, risk conscious world. No longer the work of a single “mad” scientist re-animating the dead, they now appear as the result of secret government programmes creating untreatable viruses. The zombies indiscriminately overwhelm states irrespective of wealth, technology and military strength, turning all order to chaos.

Meanwhile, the zombies themselves are evolving into much more tenacious adversaries. In Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later it takes only 20 days for society to be devastated. Charlie Higson’s Enemy series of novels have the zombies getting leadership and using tools. In the film of Max Brooks’ novel, World War Z, the seemingly superhuman athleticism of the zombies reflects the devastating springboard that vast urban populations would provide for such a disease. The film, starring Brad Pitt, had a reported budget of US$190m, demonstrating what a big business zombies have become.

Read the entire article here.

Image courtesy of Google Search.