For technologists the barriers to developing a new product have never been so low. Tools to develop, integrate and distribute software apps are to all intents negligible. Of course, most would recognize that development is often the easy part. The real difficulty lies in building an effective and sustainable marketing and communication strategy and getting the product adopted.

For technologists the barriers to developing a new product have never been so low. Tools to develop, integrate and distribute software apps are to all intents negligible. Of course, most would recognize that development is often the easy part. The real difficulty lies in building an effective and sustainable marketing and communication strategy and getting the product adopted.

The recent headlines of 17 year old British app developer Nick D’Aloisio selling his Summly app to Yahoo! for the tidy sum of $30 million, has lots of young and seasoned developers scratching their heads. After all, if a school kid can do it, why not anybody? Why not me?

Paul Graham may have some of the answers. He sold his first company to Yahoo in 1998. He now runs YCombinator a successful startup incubator. We excerpt his recent, observant and insightful essay below.

From Paul Graham:

The way to get startup ideas is not to try to think of startup ideas. It’s to look for problems, preferably problems you have yourself.

The very best startup ideas tend to have three things in common: they’re something the founders themselves want, that they themselves can build, and that few others realize are worth doing. Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo, Google, and Facebook all began this way.

Problems

Why is it so important to work on a problem you have? Among other things, it ensures the problem really exists. It sounds obvious to say you should only work on problems that exist. And yet by far the most common mistake startups make is to solve problems no one has.

I made it myself. In 1995 I started a company to put art galleries online. But galleries didn’t want to be online. It’s not how the art business works. So why did I spend 6 months working on this stupid idea? Because I didn’t pay attention to users. I invented a model of the world that didn’t correspond to reality, and worked from that. I didn’t notice my model was wrong until I tried to convince users to pay for what we’d built. Even then I took embarrassingly long to catch on. I was attached to my model of the world, and I’d spent a lot of time on the software. They had to want it!

Why do so many founders build things no one wants? Because they begin by trying to think of startup ideas. That m.o. is doubly dangerous: it doesn’t merely yield few good ideas; it yields bad ideas that sound plausible enough to fool you into working on them.

At YC we call these “made-up” or “sitcom” startup ideas. Imagine one of the characters on a TV show was starting a startup. The writers would have to invent something for it to do. But coming up with good startup ideas is hard. It’s not something you can do for the asking. So (unless they got amazingly lucky) the writers would come up with an idea that sounded plausible, but was actually bad.

For example, a social network for pet owners. It doesn’t sound obviously mistaken. Millions of people have pets. Often they care a lot about their pets and spend a lot of money on them. Surely many of these people would like a site where they could talk to other pet owners. Not all of them perhaps, but if just 2 or 3 percent were regular visitors, you could have millions of users. You could serve them targeted offers, and maybe charge for premium features.

The danger of an idea like this is that when you run it by your friends with pets, they don’t say “I would never use this.” They say “Yeah, maybe I could see using something like that.” Even when the startup launches, it will sound plausible to a lot of people. They don’t want to use it themselves, at least not right now, but they could imagine other people wanting it. Sum that reaction across the entire population, and you have zero users.

Well

When a startup launches, there have to be at least some users who really need what they’re making—not just people who could see themselves using it one day, but who want it urgently. Usually this initial group of users is small, for the simple reason that if there were something that large numbers of people urgently needed and that could be built with the amount of effort a startup usually puts into a version one, it would probably already exist. Which means you have to compromise on one dimension: you can either build something a large number of people want a small amount, or something a small number of people want a large amount. Choose the latter. Not all ideas of that type are good startup ideas, but nearly all good startup ideas are of that type.

Imagine a graph whose x axis represents all the people who might want what you’re making and whose y axis represents how much they want it. If you invert the scale on the y axis, you can envision companies as holes. Google is an immense crater: hundreds of millions of people use it, and they need it a lot. A startup just starting out can’t expect to excavate that much volume. So you have two choices about the shape of hole you start with. You can either dig a hole that’s broad but shallow, or one that’s narrow and deep, like a well.

Made-up startup ideas are usually of the first type. Lots of people are mildly interested in a social network for pet owners.

Nearly all good startup ideas are of the second type. Microsoft was a well when they made Altair Basic. There were only a couple thousand Altair owners, but without this software they were programming in machine language. Thirty years later Facebook had the same shape. Their first site was exclusively for Harvard students, of which there are only a few thousand, but those few thousand users wanted it a lot.

When you have an idea for a startup, ask yourself: who wants this right now? Who wants this so much that they’ll use it even when it’s a crappy version one made by a two-person startup they’ve never heard of? If you can’t answer that, the idea is probably bad.

You don’t need the narrowness of the well per se. It’s depth you need; you get narrowness as a byproduct of optimizing for depth (and speed). But you almost always do get it. In practice the link between depth and narrowness is so strong that it’s a good sign when you know that an idea will appeal strongly to a specific group or type of user.

But while demand shaped like a well is almost a necessary condition for a good startup idea, it’s not a sufficient one. If Mark Zuckerberg had built something that could only ever have appealed to Harvard students, it would not have been a good startup idea. Facebook was a good idea because it started with a small market there was a fast path out of. Colleges are similar enough that if you build a facebook that works at Harvard, it will work at any college. So you spread rapidly through all the colleges. Once you have all the college students, you get everyone else simply by letting them in.

Similarly for Microsoft: Basic for the Altair; Basic for other machines; other languages besides Basic; operating systems; applications; IPO.

Self

How do you tell whether there’s a path out of an idea? How do you tell whether something is the germ of a giant company, or just a niche product? Often you can’t. The founders of Airbnb didn’t realize at first how big a market they were tapping. Initially they had a much narrower idea. They were going to let hosts rent out space on their floors during conventions. They didn’t foresee the expansion of this idea; it forced itself upon them gradually. All they knew at first is that they were onto something. That’s probably as much as Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg knew at first.

Occasionally it’s obvious from the beginning when there’s a path out of the initial niche. And sometimes I can see a path that’s not immediately obvious; that’s one of our specialties at YC. But there are limits to how well this can be done, no matter how much experience you have. The most important thing to understand about paths out of the initial idea is the meta-fact that these are hard to see.

So if you can’t predict whether there’s a path out of an idea, how do you choose between ideas? The truth is disappointing but interesting: if you’re the right sort of person, you have the right sort of hunches. If you’re at the leading edge of a field that’s changing fast, when you have a hunch that something is worth doing, you’re more likely to be right.

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig says:

You want to know how to paint a perfect painting? It’s easy. Make yourself perfect and then just paint naturally.

I’ve wondered about that passage since I read it in high school. I’m not sure how useful his advice is for painting specifically, but it fits this situation well. Empirically, the way to have good startup ideas is to become the sort of person who has them.

Being at the leading edge of a field doesn’t mean you have to be one of the people pushing it forward. You can also be at the leading edge as a user. It was not so much because he was a programmer that Facebook seemed a good idea to Mark Zuckerberg as because he used computers so much. If you’d asked most 40 year olds in 2004 whether they’d like to publish their lives semi-publicly on the Internet, they’d have been horrified at the idea. But Mark already lived online; to him it seemed natural.

Paul Buchheit says that people at the leading edge of a rapidly changing field “live in the future.” Combine that with Pirsig and you get:

Live in the future, then build what’s missing.

That describes the way many if not most of the biggest startups got started. Neither Apple nor Yahoo nor Google nor Facebook were even supposed to be companies at first. They grew out of things their founders built because there seemed a gap in the world.

If you look at the way successful founders have had their ideas, it’s generally the result of some external stimulus hitting a prepared mind. Bill Gates and Paul Allen hear about the Altair and think “I bet we could write a Basic interpreter for it.” Drew Houston realizes he’s forgotten his USB stick and thinks “I really need to make my files live online.” Lots of people heard about the Altair. Lots forgot USB sticks. The reason those stimuli caused those founders to start companies was that their experiences had prepared them to notice the opportunities they represented.

The verb you want to be using with respect to startup ideas is not “think up” but “notice.” At YC we call ideas that grow naturally out of the founders’ own experiences “organic” startup ideas. The most successful startups almost all begin this way.

That may not have been what you wanted to hear. You may have expected recipes for coming up with startup ideas, and instead I’m telling you that the key is to have a mind that’s prepared in the right way. But disappointing though it may be, this is the truth. And it is a recipe of a sort, just one that in the worst case takes a year rather than a weekend.

If you’re not at the leading edge of some rapidly changing field, you can get to one. For example, anyone reasonably smart can probably get to an edge of programming (e.g. building mobile apps) in a year. Since a successful startup will consume at least 3-5 years of your life, a year’s preparation would be a reasonable investment. Especially if you’re also looking for a cofounder.

You don’t have to learn programming to be at the leading edge of a domain that’s changing fast. Other domains change fast. But while learning to hack is not necessary, it is for the forseeable future sufficient. As Marc Andreessen put it, software is eating the world, and this trend has decades left to run.

Knowing how to hack also means that when you have ideas, you’ll be able to implement them. That’s not absolutely necessary (Jeff Bezos couldn’t) but it’s an advantage. It’s a big advantage, when you’re considering an idea like putting a college facebook online, if instead of merely thinking “That’s an interesting idea,” you can think instead “That’s an interesting idea. I’ll try building an initial version tonight.” It’s even better when you’re both a programmer and the target user, because then the cycle of generating new versions and testing them on users can happen inside one head.

Noticing

Once you’re living in the future in some respect, the way to notice startup ideas is to look for things that seem to be missing. If you’re really at the leading edge of a rapidly changing field, there will be things that are obviously missing. What won’t be obvious is that they’re startup ideas. So if you want to find startup ideas, don’t merely turn on the filter “What’s missing?” Also turn off every other filter, particularly “Could this be a big company?” There’s plenty of time to apply that test later. But if you’re thinking about that initially, it may not only filter out lots of good ideas, but also cause you to focus on bad ones.

Most things that are missing will take some time to see. You almost have to trick yourself into seeing the ideas around you.

But you know the ideas are out there. This is not one of those problems where there might not be an answer. It’s impossibly unlikely that this is the exact moment when technological progress stops. You can be sure people are going to build things in the next few years that will make you think “What did I do before x?”

And when these problems get solved, they will probably seem flamingly obvious in retrospect. What you need to do is turn off the filters that usually prevent you from seeing them. The most powerful is simply taking the current state of the world for granted. Even the most radically open-minded of us mostly do that. You couldn’t get from your bed to the front door if you stopped to question everything.

But if you’re looking for startup ideas you can sacrifice some of the efficiency of taking the status quo for granted and start to question things. Why is your inbox overflowing? Because you get a lot of email, or because it’s hard to get email out of your inbox? Why do you get so much email? What problems are people trying to solve by sending you email? Are there better ways to solve them? And why is it hard to get emails out of your inbox? Why do you keep emails around after you’ve read them? Is an inbox the optimal tool for that?

Pay particular attention to things that chafe you. The advantage of taking the status quo for granted is not just that it makes life (locally) more efficient, but also that it makes life more tolerable. If you knew about all the things we’ll get in the next 50 years but don’t have yet, you’d find present day life pretty constraining, just as someone from the present would if they were sent back 50 years in a time machine. When something annoys you, it could be because you’re living in the future.

When you find the right sort of problem, you should probably be able to describe it as obvious, at least to you. When we started Viaweb, all the online stores were built by hand, by web designers making individual HTML pages. It was obvious to us as programmers that these sites would have to be generated by software.

Which means, strangely enough, that coming up with startup ideas is a question of seeing the obvious. That suggests how weird this process is: you’re trying to see things that are obvious, and yet that you hadn’t seen.

Since what you need to do here is loosen up your own mind, it may be best not to make too much of a direct frontal attack on the problem—i.e. to sit down and try to think of ideas. The best plan may be just to keep a background process running, looking for things that seem to be missing. Work on hard problems, driven mainly by curiousity, but have a second self watching over your shoulder, taking note of gaps and anomalies.

Give yourself some time. You have a lot of control over the rate at which you turn yours into a prepared mind, but you have less control over the stimuli that spark ideas when they hit it. If Bill Gates and Paul Allen had constrained themselves to come up with a startup idea in one month, what if they’d chosen a month before the Altair appeared? They probably would have worked on a less promising idea. Drew Houston did work on a less promising idea before Dropbox: an SAT prep startup. But Dropbox was a much better idea, both in the absolute sense and also as a match for his skills.

A good way to trick yourself into noticing ideas is to work on projects that seem like they’d be cool. If you do that, you’ll naturally tend to build things that are missing. It wouldn’t seem as interesting to build something that already existed.

Just as trying to think up startup ideas tends to produce bad ones, working on things that could be dismissed as “toys” often produces good ones. When something is described as a toy, that means it has everything an idea needs except being important. It’s cool; users love it; it just doesn’t matter. But if you’re living in the future and you build something cool that users love, it may matter more than outsiders think. Microcomputers seemed like toys when Apple and Microsoft started working on them. I’m old enough to remember that era; the usual term for people with their own microcomputers was “hobbyists.” BackRub seemed like an inconsequential science project. The Facebook was just a way for undergrads to stalk one another.

At YC we’re excited when we meet startups working on things that we could imagine know-it-alls on forums dismissing as toys. To us that’s positive evidence an idea is good.

If you can afford to take a long view (and arguably you can’t afford not to), you can turn “Live in the future and build what’s missing” into something even better:

Live in the future and build what seems interesting.

School

That’s what I’d advise college students to do, rather than trying to learn about “entrepreneurship.” “Entrepreneurship” is something you learn best by doing it. The examples of the most successful founders make that clear. What you should be spending your time on in college is ratcheting yourself into the future. College is an incomparable opportunity to do that. What a waste to sacrifice an opportunity to solve the hard part of starting a startup—becoming the sort of person who can have organic startup ideas—by spending time learning about the easy part. Especially since you won’t even really learn about it, any more than you’d learn about sex in a class. All you’ll learn is the words for things.

The clash of domains is a particularly fruitful source of ideas. If you know a lot about programming and you start learning about some other field, you’ll probably see problems that software could solve. In fact, you’re doubly likely to find good problems in another domain: (a) the inhabitants of that domain are not as likely as software people to have already solved their problems with software, and (b) since you come into the new domain totally ignorant, you don’t even know what the status quo is to take it for granted.

So if you’re a CS major and you want to start a startup, instead of taking a class on entrepreneurship you’re better off taking a class on, say, genetics. Or better still, go work for a biotech company. CS majors normally get summer jobs at computer hardware or software companies. But if you want to find startup ideas, you might do better to get a summer job in some unrelated field.

Or don’t take any extra classes, and just build things. It’s no coincidence that Microsoft and Facebook both got started in January. At Harvard that is (or was) Reading Period, when students have no classes to attend because they’re supposed to be studying for finals.

But don’t feel like you have to build things that will become startups. That’s premature optimization. Just build things. Preferably with other students. It’s not just the classes that make a university such a good place to crank oneself into the future. You’re also surrounded by other people trying to do the same thing. If you work together with them on projects, you’ll end up producing not just organic ideas, but organic ideas with organic founding teams—and that, empirically, is the best combination.

Beware of research. If an undergrad writes something all his friends start using, it’s quite likely to represent a good startup idea. Whereas a PhD dissertation is extremely unlikely to. For some reason, the more a project has to count as research, the less likely it is to be something that could be turned into a startup. [10] I think the reason is that the subset of ideas that count as research is so narrow that it’s unlikely that a project that satisfied that constraint would also satisfy the orthogonal constraint of solving users’ problems. Whereas when students (or professors) build something as a side-project, they automatically gravitate toward solving users’ problems—perhaps even with an additional energy that comes from being freed from the constraints of research.

Competition

Because a good idea should seem obvious, when you have one you’ll tend to feel that you’re late. Don’t let that deter you. Worrying that you’re late is one of the signs of a good idea. Ten minutes of searching the web will usually settle the question. Even if you find someone else working on the same thing, you’re probably not too late. It’s exceptionally rare for startups to be killed by competitors—so rare that you can almost discount the possibility. So unless you discover a competitor with the sort of lock-in that would prevent users from choosing you, don’t discard the idea.

If you’re uncertain, ask users. The question of whether you’re too late is subsumed by the question of whether anyone urgently needs what you plan to make. If you have something that no competitor does and that some subset of users urgently need, you have a beachhead.

The question then is whether that beachhead is big enough. Or more importantly, who’s in it: if the beachhead consists of people doing something lots more people will be doing in the future, then it’s probably big enough no matter how small it is. For example, if you’re building something differentiated from competitors by the fact that it works on phones, but it only works on the newest phones, that’s probably a big enough beachhead.

Err on the side of doing things where you’ll face competitors. Inexperienced founders usually give competitors more credit than they deserve. Whether you succeed depends far more on you than on your competitors. So better a good idea with competitors than a bad one without.

You don’t need to worry about entering a “crowded market” so long as you have a thesis about what everyone else in it is overlooking. In fact that’s a very promising starting point. Google was that type of idea. Your thesis has to be more precise than “we’re going to make an x that doesn’t suck” though. You have to be able to phrase it in terms of something the incumbents are overlooking. Best of all is when you can say that they didn’t have the courage of their convictions, and that your plan is what they’d have done if they’d followed through on their own insights. Google was that type of idea too. The search engines that preceded them shied away from the most radical implications of what they were doing—particularly that the better a job they did, the faster users would leave.

A crowded market is actually a good sign, because it means both that there’s demand and that none of the existing solutions are good enough. A startup can’t hope to enter a market that’s obviously big and yet in which they have no competitors. So any startup that succeeds is either going to be entering a market with existing competitors, but armed with some secret weapon that will get them all the users (like Google), or entering a market that looks small but which will turn out to be big (like Microsoft).

Filters

There are two more filters you’ll need to turn off if you want to notice startup ideas: the unsexy filter and the schlep filter.

Most programmers wish they could start a startup by just writing some brilliant code, pushing it to a server, and having users pay them lots of money. They’d prefer not to deal with tedious problems or get involved in messy ways with the real world. Which is a reasonable preference, because such things slow you down. But this preference is so widespread that the space of convenient startup ideas has been stripped pretty clean. If you let your mind wander a few blocks down the street to the messy, tedious ideas, you’ll find valuable ones just sitting there waiting to be implemented.

The schlep filter is so dangerous that I wrote a separate essay about the condition it induces, which I called schlep blindness. I gave Stripe as an example of a startup that benefited from turning off this filter, and a pretty striking example it is. Thousands of programmers were in a position to see this idea; thousands of programmers knew how painful it was to process payments before Stripe. But when they looked for startup ideas they didn’t see this one, because unconsciously they shrank from having to deal with payments. And dealing with payments is a schlep for Stripe, but not an intolerable one. In fact they might have had net less pain; because the fear of dealing with payments kept most people away from this idea, Stripe has had comparatively smooth sailing in other areas that are sometimes painful, like user acquisition. They didn’t have to try very hard to make themselves heard by users, because users were desperately waiting for what they were building.

The unsexy filter is similar to the schlep filter, except it keeps you from working on problems you despise rather than ones you fear. We overcame this one to work on Viaweb. There were interesting things about the architecture of our software, but we weren’t interested in ecommerce per se. We could see the problem was one that needed to be solved though.

Turning off the schlep filter is more important than turning off the unsexy filter, because the schlep filter is more likely to be an illusion. And even to the degree it isn’t, it’s a worse form of self-indulgence. Starting a successful startup is going to be fairly laborious no matter what. Even if the product doesn’t entail a lot of schleps, you’ll still have plenty dealing with investors, hiring and firing people, and so on. So if there’s some idea you think would be cool but you’re kept away from by fear of the schleps involved, don’t worry: any sufficiently good idea will have as many.

The unsexy filter, while still a source of error, is not as entirely useless as the schlep filter. If you’re at the leading edge of a field that’s changing rapidly, your ideas about what’s sexy will be somewhat correlated with what’s valuable in practice. Particularly as you get older and more experienced. Plus if you find an idea sexy, you’ll work on it more enthusiastically.

Recipes

While the best way to discover startup ideas is to become the sort of person who has them and then build whatever interests you, sometimes you don’t have that luxury. Sometimes you need an idea now. For example, if you’re working on a startup and your initial idea turns out to be bad.

For the rest of this essay I’ll talk about tricks for coming up with startup ideas on demand. Although empirically you’re better off using the organic strategy, you could succeed this way. You just have to be more disciplined. When you use the organic method, you don’t even notice an idea unless it’s evidence that something is truly missing. But when you make a conscious effort to think of startup ideas, you have to replace this natural constraint with self-discipline. You’ll see a lot more ideas, most of them bad, so you need to be able to filter them.

One of the biggest dangers of not using the organic method is the example of the organic method. Organic ideas feel like inspirations. There are a lot of stories about successful startups that began when the founders had what seemed a crazy idea but “just knew” it was promising. When you feel that about an idea you’ve had while trying to come up with startup ideas, you’re probably mistaken.

When searching for ideas, look in areas where you have some expertise. If you’re a database expert, don’t build a chat app for teenagers (unless you’re also a teenager). Maybe it’s a good idea, but you can’t trust your judgment about that, so ignore it. There have to be other ideas that involve databases, and whose quality you can judge. Do you find it hard to come up with good ideas involving databases? That’s because your expertise raises your standards. Your ideas about chat apps are just as bad, but you’re giving yourself a Dunning-Kruger pass in that domain.

The place to start looking for ideas is things you need. There must be things you need.

One good trick is to ask yourself whether in your previous job you ever found yourself saying “Why doesn’t someone make x? If someone made x we’d buy it in a second.” If you can think of any x people said that about, you probably have an idea. You know there’s demand, and people don’t say that about things that are impossible to build.

More generally, try asking yourself whether there’s something unusual about you that makes your needs different from most other people’s. You’re probably not the only one. It’s especially good if you’re different in a way people will increasingly be.

If you’re changing ideas, one unusual thing about you is the idea you’d previously been working on. Did you discover any needs while working on it? Several well-known startups began this way. Hotmail began as something its founders wrote to talk about their previous startup idea while they were working at their day jobs. [15]

A particularly promising way to be unusual is to be young. Some of the most valuable new ideas take root first among people in their teens and early twenties. And while young founders are at a disadvantage in some respects, they’re the only ones who really understand their peers. It would have been very hard for someone who wasn’t a college student to start Facebook. So if you’re a young founder (under 23 say), are there things you and your friends would like to do that current technology won’t let you?

The next best thing to an unmet need of your own is an unmet need of someone else. Try talking to everyone you can about the gaps they find in the world. What’s missing? What would they like to do that they can’t? What’s tedious or annoying, particularly in their work? Let the conversation get general; don’t be trying too hard to find startup ideas. You’re just looking for something to spark a thought. Maybe you’ll notice a problem they didn’t consciously realize they had, because you know how to solve it.

When you find an unmet need that isn’t your own, it may be somewhat blurry at first. The person who needs something may not know exactly what they need. In that case I often recommend that founders act like consultants—that they do what they’d do if they’d been retained to solve the problems of this one user. People’s problems are similar enough that nearly all the code you write this way will be reusable, and whatever isn’t will be a small price to start out certain that you’ve reached the bottom of the well.

One way to ensure you do a good job solving other people’s problems is to make them your own. When Rajat Suri of E la Carte decided to write software for restaurants, he got a job as a waiter to learn how restaurants worked. That may seem like taking things to extremes, but startups are extreme. We love it when founders do such things.

In fact, one strategy I recommend to people who need a new idea is not merely to turn off their schlep and unsexy filters, but to seek out ideas that are unsexy or involve schleps. Don’t try to start Twitter. Those ideas are so rare that you can’t find them by looking for them. Make something unsexy that people will pay you for.

A good trick for bypassing the schlep and to some extent the unsexy filter is to ask what you wish someone else would build, so that you could use it. What would you pay for right now?

Since startups often garbage-collect broken companies and industries, it can be a good trick to look for those that are dying, or deserve to, and try to imagine what kind of company would profit from their demise. For example, journalism is in free fall at the moment. But there may still be money to be made from something like journalism. What sort of company might cause people in the future to say “this replaced journalism” on some axis?

But imagine asking that in the future, not now. When one company or industry replaces another, it usually comes in from the side. So don’t look for a replacement for x; look for something that people will later say turned out to be a replacement for x. And be imaginative about the axis along which the replacement occurs. Traditional journalism, for example, is a way for readers to get information and to kill time, a way for writers to make money and to get attention, and a vehicle for several different types of advertising. It could be replaced on any of these axes (it has already started to be on most).

When startups consume incumbents, they usually start by serving some small but important market that the big players ignore. It’s particularly good if there’s an admixture of disdain in the big players’ attitude, because that often misleads them. For example, after Steve Wozniak built the computer that became the Apple I, he felt obliged to give his then-employer Hewlett-Packard the option to produce it. Fortunately for him, they turned it down, and one of the reasons they did was that it used a TV for a monitor, which seemed intolerably déclassé to a high-end hardware company like HP was at the time.

Are there groups of scruffy but sophisticated users like the early microcomputer “hobbyists” that are currently being ignored by the big players? A startup with its sights set on bigger things can often capture a small market easily by expending an effort that wouldn’t be justified by that market alone.

Similarly, since the most successful startups generally ride some wave bigger than themselves, it could be a good trick to look for waves and ask how one could benefit from them. The prices of gene sequencing and 3D printing are both experiencing Moore’s Law-like declines. What new things will we be able to do in the new world we’ll have in a few years? What are we unconsciously ruling out as impossible that will soon be possible?

Organic

But talking about looking explicitly for waves makes it clear that such recipes are plan B for getting startup ideas. Looking for waves is essentially a way to simulate the organic method. If you’re at the leading edge of some rapidly changing field, you don’t have to look for waves; you are the wave.

Finding startup ideas is a subtle business, and that’s why most people who try fail so miserably. It doesn’t work well simply to try to think of startup ideas. If you do that, you get bad ones that sound dangerously plausible. The best approach is more indirect: if you have the right sort of background, good startup ideas will seem obvious to you. But even then, not immediately. It takes time to come across situations where you notice something missing. And often these gaps won’t seem to be ideas for companies, just things that would be interesting to build. Which is why it’s good to have the time and the inclination to build things just because they’re interesting.

Live in the future and build what seems interesting. Strange as it sounds, that’s the real recipe.

Read the entire article after the jump.

Image: Nick D’Aloisio with his Summly app. Courtesy of Telegraph.

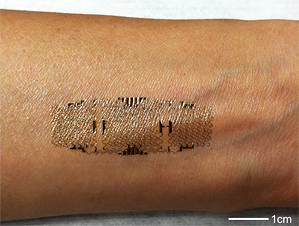

Forget wearable electronics, like Google Glass. That’s so, well, 2012. Welcome to the new world of epidermal electronics — electronic tattoos that contain circuits and sensors printed directly on to the body.

Forget wearable electronics, like Google Glass. That’s so, well, 2012. Welcome to the new world of epidermal electronics — electronic tattoos that contain circuits and sensors printed directly on to the body.

You might expect to find police drones in the pages of a science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick or Iain M. Banks. But by 2015, citizens of the United States may well see these unmanned flying machines patrolling the skies over the homeland. The U.S. government recently pledged to loosen Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) restrictions that would allow local law enforcement agencies to use drones in just a few short years. So, soon the least of your worries will be traffic signal cameras and the local police officer armed with a radar gun. Our home-grown drones are likely to be deployed first for surveillance. But, undoubtedly armaments will follow. Hellfire missiles over Helena, Montana anyone?

You might expect to find police drones in the pages of a science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick or Iain M. Banks. But by 2015, citizens of the United States may well see these unmanned flying machines patrolling the skies over the homeland. The U.S. government recently pledged to loosen Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) restrictions that would allow local law enforcement agencies to use drones in just a few short years. So, soon the least of your worries will be traffic signal cameras and the local police officer armed with a radar gun. Our home-grown drones are likely to be deployed first for surveillance. But, undoubtedly armaments will follow. Hellfire missiles over Helena, Montana anyone? Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world.

Edward Tufte built the first little blue box in 1962. The blue box contained home-made circuitry and a tone generator that could place free calls over the phone network to anywhere in the world.

Golden Spike, a Boulder Colorado based company, has an interesting proposition for the world’s restless billionaires. It is offering a two-seat trip to the Moon, and back, for a tidy sum of $1.5 billion. And, the company is even throwing in a moon-walk. The first trip is planned for 2020.

Golden Spike, a Boulder Colorado based company, has an interesting proposition for the world’s restless billionaires. It is offering a two-seat trip to the Moon, and back, for a tidy sum of $1.5 billion. And, the company is even throwing in a moon-walk. The first trip is planned for 2020. Despite what seems to be an overwhelmingly digital shift in our lives, we still live in a world of steam. Steam plays a vital role in generating most of the world’s electricity, steam heats our buildings (especially if you live in New York City), steam sterilizes our medical supplies.

Despite what seems to be an overwhelmingly digital shift in our lives, we still live in a world of steam. Steam plays a vital role in generating most of the world’s electricity, steam heats our buildings (especially if you live in New York City), steam sterilizes our medical supplies.

Starting up a new business was once a demanding and complex process, often undertaken in anonymity in the long shadows between the hours of a regular job. It still is over course. However nowadays “the startup” has become more of an event. The tech sector has raised this to a fine art by spawning an entire self-sustaining and self-promoting industry around startups.

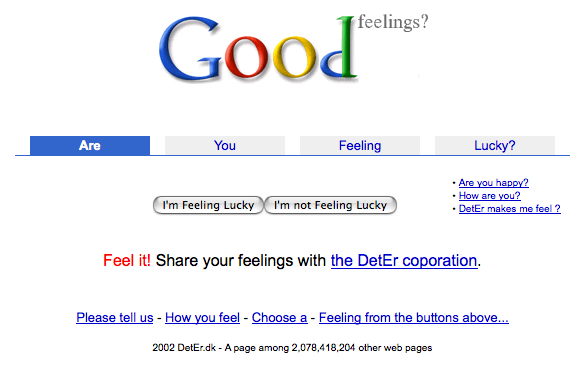

Starting up a new business was once a demanding and complex process, often undertaken in anonymity in the long shadows between the hours of a regular job. It still is over course. However nowadays “the startup” has become more of an event. The tech sector has raised this to a fine art by spawning an entire self-sustaining and self-promoting industry around startups. We all have owned or have used or have come far too close to a technology that we absolutely abhor and wish numerous curses upon its inventors. Said gizmo may be the unfathomable VCR, the forever lost TV remote, the tinny sounding Sony Walkman replete with unraveling cassette tape, the Blackberry, or even Facebook.

We all have owned or have used or have come far too close to a technology that we absolutely abhor and wish numerous curses upon its inventors. Said gizmo may be the unfathomable VCR, the forever lost TV remote, the tinny sounding Sony Walkman replete with unraveling cassette tape, the Blackberry, or even Facebook.

Social media is great for notifying members in one’s circle of events in the here and now. Of course, most events turn out to be rather trivial, of the “what I ate for dinner” kind. However, social media also has a role in spreading word of more momentous social and political events; the Arab Spring comes to mind.

Social media is great for notifying members in one’s circle of events in the here and now. Of course, most events turn out to be rather trivial, of the “what I ate for dinner” kind. However, social media also has a role in spreading word of more momentous social and political events; the Arab Spring comes to mind.

We excerpt an interview with big data pioneer and computer scientist, Alex Pentland, via the Edge. Pentland is a leading thinker in computational social science and currently directs the Human Dynamics Laboratory at MIT.

We excerpt an interview with big data pioneer and computer scientist, Alex Pentland, via the Edge. Pentland is a leading thinker in computational social science and currently directs the Human Dynamics Laboratory at MIT.

Thirty years ago today Professor Scott Fahlman of Carnegie Mellon University sent what is believed to be the first emoticon embedded in an email. The symbol, :-), which he proposed as a joke marker, spread rapidly, morphed and evolved into a universe of symbolic nods, winks, and cyber-emotions.

Thirty years ago today Professor Scott Fahlman of Carnegie Mellon University sent what is believed to be the first emoticon embedded in an email. The symbol, :-), which he proposed as a joke marker, spread rapidly, morphed and evolved into a universe of symbolic nods, winks, and cyber-emotions.

There is no doubt that online reviews for products and services, from books to news cars to a vacation spot, have revolutionized shopping behavior. Internet and mobile technology has made gathering, reviewing and publishing open and honest crowdsourced opinion simple, efficient and ubiquitous.

There is no doubt that online reviews for products and services, from books to news cars to a vacation spot, have revolutionized shopping behavior. Internet and mobile technology has made gathering, reviewing and publishing open and honest crowdsourced opinion simple, efficient and ubiquitous. Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.