Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

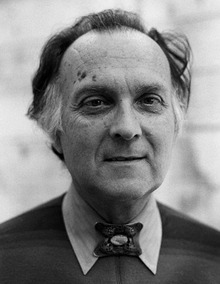

We excerpt a lengthy interview with Jaron Lanier over at the Edge. Lanier, a pioneer in the sphere of virtual reality, offers some well-laid arguments for and against concentration of market power as enabled by information systems and the internet. Though he leaves his most powerful criticism at the doors of Google. Their (in)famous corporate mantra — “do no evil” — will start to look remarkably disingenuous.

[div class=attrib]From the Edge:[end-div]

I’ve focused quite a lot on how this stealthy component of computation can affect our sense of ourselves, what it is to be a person. But lately I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to economics.

In particular, I’m interested in a pretty simple problem, but one that is devastating. In recent years, many of us have worked very hard to make the Internet grow, to become available to people, and that’s happened. It’s one of the great topics of mankind of this era. Everyone’s into Internet things, and yet we have this huge global economic trouble. If you had talked to anyone involved in it twenty years ago, everyone would have said that the ability for people to inexpensively have access to a tremendous global computation and networking facility ought to create wealth. This ought to create wellbeing; this ought to create this incredible expansion in just people living decently, and in personal liberty. And indeed, some of that’s happened. Yet if you look at the big picture, it obviously isn’t happening enough, if it’s happening at all.

The situation reminds me a little bit of something that is deeply connected, which is the way that computer networks transformed finance. You have more and more complex financial instruments, derivatives and so forth, and high frequency trading, all these extraordinary constructions that would be inconceivable without computation and networking technology.

At the start, the idea was, “Well, this is all in the service of the greater good because we’ll manage risk so much better, and we’ll increase the intelligence with which we collectively make decisions.” Yet if you look at what happened, risk was increased instead of decreased.

… We were doing a great job through the turn of the century. In the ’80s and ’90s, one of the things I liked about being in the Silicon Valley community was that we were growing the middle class. The personal computer revolution could have easily been mostly about enterprises. It could have been about just fighting IBM and getting computers on desks in big corporations or something, instead of this notion of the consumer, ordinary person having access to a computer, of a little mom and pop shop having a computer, and owning their own information. When you own information, you have power. Information is power. The personal computer gave people their own information, and it enabled a lot of lives.

… But at any rate, the Apple idea is that instead of the personal computer model where people own their own information, and everybody can be a creator as well as a consumer, we’re moving towards this iPad, iPhone model where it’s not as adequate for media creation as the real media creation tools, and even though you can become a seller over the network, you have to pass through Apple’s gate to accept what you do, and your chances of doing well are very small, and it’s not a person to person thing, it’s a business through a hub, through Apple to others, and it doesn’t create a middle class, it creates a new kind of upper class.

Google has done something that might even be more destructive of the middle class, which is they’ve said, “Well, since Moore’s law makes computation really cheap, let’s just give away the computation, but keep the data.” And that’s a disaster.

What’s happened now is that we’ve created this new regimen where the bigger your computer servers are, the more smart mathematicians you have working for you, and the more connected you are, the more powerful and rich you are. (Unless you own an oil field, which is the old way.) II benefit from it because I’m close to the big servers, but basically wealth is measured by how close you are to one of the big servers, and the servers have started to act like private spying agencies, essentially.

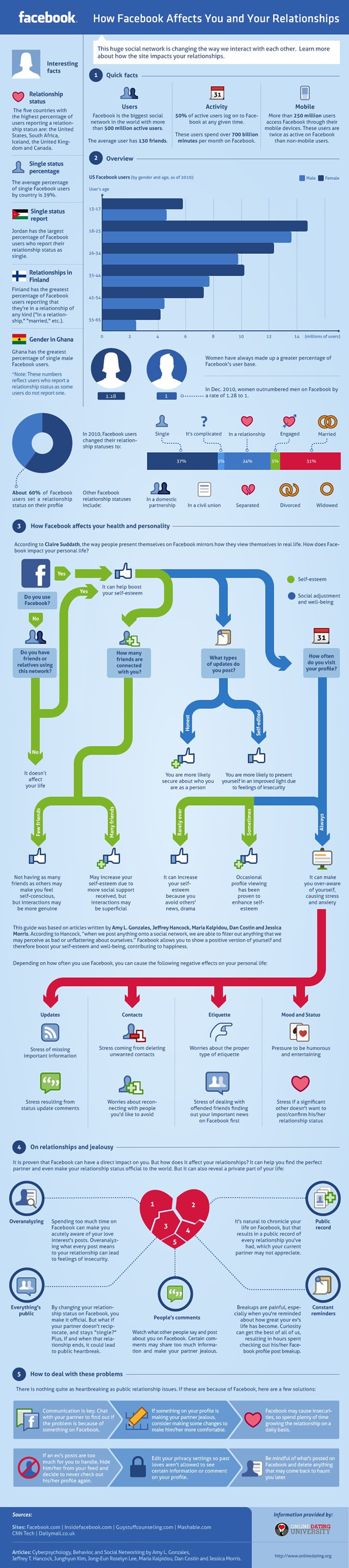

With Google, or with Facebook, if they can ever figure out how to steal some of Google’s business, there’s this notion that you get all of this stuff for free, except somebody else owns the data, and they use the data to sell access to you, and the ability to manipulate you, to third parties that you don’t necessarily get to know about. The third parties tend to be kind of tawdry.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Jaron Lanier.[end-div]

Over the last couple of years a number of researchers have upended conventional wisdom by finding that complex decisions, for instance, those having lots of variables, are better “made” through our emotional system. This flies in the face of the commonly held belief that complexity is best handled by our rational side.

Over the last couple of years a number of researchers have upended conventional wisdom by finding that complex decisions, for instance, those having lots of variables, are better “made” through our emotional system. This flies in the face of the commonly held belief that complexity is best handled by our rational side.

[div class=attrib]From Rationally Speaking:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Rationally Speaking:[end-div]

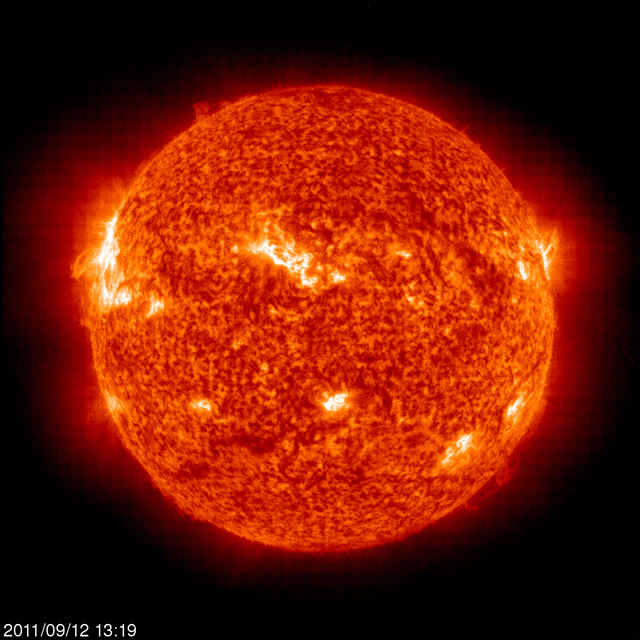

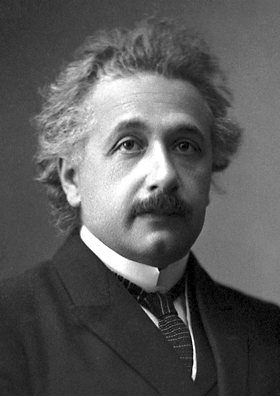

The world of particle physics is agog with recent news of an experiment that shows a very unexpected result – sub-atomic particles traveling faster than the speed of light. If verified and independently replicated the results would violate one of the universe’s fundamental properties described by Einstein in the Special Theory of Relativity. The speed of light — 186,282 miles per second (299,792 kilometers per second) — has long been considered an absolute cosmic speed limit.

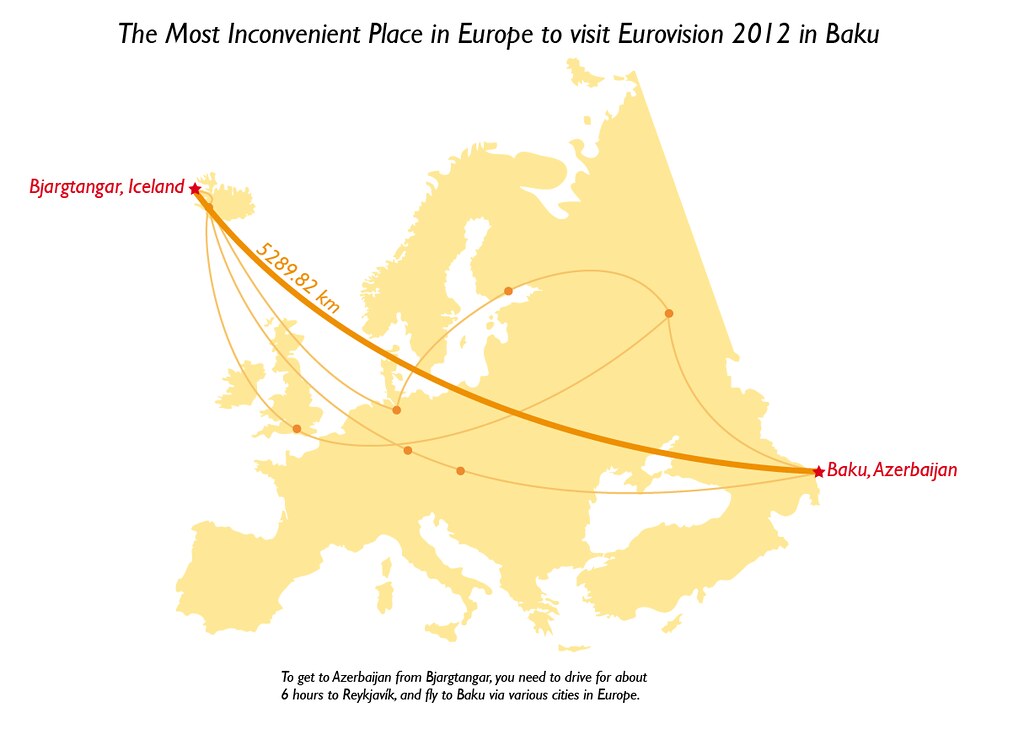

The world of particle physics is agog with recent news of an experiment that shows a very unexpected result – sub-atomic particles traveling faster than the speed of light. If verified and independently replicated the results would violate one of the universe’s fundamental properties described by Einstein in the Special Theory of Relativity. The speed of light — 186,282 miles per second (299,792 kilometers per second) — has long been considered an absolute cosmic speed limit. If you grew up in Europe or have spent at least 6 months there over the last 50 years you’ll have collided with the Eurovision Song Contest.

If you grew up in Europe or have spent at least 6 months there over the last 50 years you’ll have collided with the Eurovision Song Contest. You will have heard of the River Thames, the famous swathe of grey that cuts a watery path through London. You may even have heard of several of London’s prominent canals, such as the Grand Union Canal and Regent’s Canal. But, you probably will not have heard of the mysterious River Fleet that meanders through eerie tunnels beneath the city.

You will have heard of the River Thames, the famous swathe of grey that cuts a watery path through London. You may even have heard of several of London’s prominent canals, such as the Grand Union Canal and Regent’s Canal. But, you probably will not have heard of the mysterious River Fleet that meanders through eerie tunnels beneath the city.

Aside from founding classical mechanics — think universal gravitation and laws of motion, laying the building blocks of calculus, and inventing the reflecting telescope Isaac Newton made time for spiritual pursuits. In fact, Newton was a highly religious individual (though a somewhat unorthodox Christian).

Aside from founding classical mechanics — think universal gravitation and laws of motion, laying the building blocks of calculus, and inventing the reflecting telescope Isaac Newton made time for spiritual pursuits. In fact, Newton was a highly religious individual (though a somewhat unorthodox Christian). [div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div] A poem by Anthony Hecht this week. On Hecht, Poetry Foundation remarks, “[o]ne of the leading voices of his generation, Anthony Hecht’s poetry is known for its masterful use of traditional forms and linguistic control.”

A poem by Anthony Hecht this week. On Hecht, Poetry Foundation remarks, “[o]ne of the leading voices of his generation, Anthony Hecht’s poetry is known for its masterful use of traditional forms and linguistic control.”

General scientific consensus suggests that our universe has no pre-defined destiny. While a number of current theories propose anything from a final Big Crush to an accelerating expansion into cold nothingness the future plan for the universe is not pre-determined. Unfortunately, our increasingly sophisticated scientific tools are still to meager to test and answer these questions definitively. So, theorists currently seem to have the upper hand. And, now yet another theory puts current cosmological thinking on its head by proposing that the future is pre-destined and that it may even reach back into the past to shape the present. Confused? Read on!

General scientific consensus suggests that our universe has no pre-defined destiny. While a number of current theories propose anything from a final Big Crush to an accelerating expansion into cold nothingness the future plan for the universe is not pre-determined. Unfortunately, our increasingly sophisticated scientific tools are still to meager to test and answer these questions definitively. So, theorists currently seem to have the upper hand. And, now yet another theory puts current cosmological thinking on its head by proposing that the future is pre-destined and that it may even reach back into the past to shape the present. Confused? Read on! Neuroscientists continue to find interesting experimental evidence that we do not have free will. Many philosophers continue to dispute this notion and cite inconclusive results and lack of holistic understanding of decision-making on the part of brain scientists. An

Neuroscientists continue to find interesting experimental evidence that we do not have free will. Many philosophers continue to dispute this notion and cite inconclusive results and lack of holistic understanding of decision-making on the part of brain scientists. An  “You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate:

“You cannot be serious”, goes the oft quoted opening to a John McEnroe javelin thrown at an unsuspecting tennis umpire. This leads us to an earnest review of what is means to be serious from Lee Siegel’s new book, “Are You Serious?” As Michael Agger points out for Slate: Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

Twenty or so years ago the economic prognosticators and technology pundits would all have had us believe that the internet would transform society; it would level the playing field; it would help the little guy compete against the corporate behemoth; it would make us all “socially” rich if not financially. Yet, the promise of those early, heady days seems remarkably narrow nowadays. What happened? Or rather, what didn’t happen?

As any Italian speaker would attest, the moon, of course is utterly feminine. It is “la luna”. Now, to a German it is “der mond”, and very masculine.

As any Italian speaker would attest, the moon, of course is utterly feminine. It is “la luna”. Now, to a German it is “der mond”, and very masculine.

This week theDiagonal triangulates its sights on the topic of language and communication. So, we introduce an apt poem by Robert Duncan. Of Robert Duncan, Poetry Foundation writes:

This week theDiagonal triangulates its sights on the topic of language and communication. So, we introduce an apt poem by Robert Duncan. Of Robert Duncan, Poetry Foundation writes: [div class=attrib]From Neuroskeptic:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Neuroskeptic:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From Project Syndicate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Project Syndicate:[end-div]